In the Himalayas, climate change bites and human health suffers

In Indian Kashmir, hospital wards filled up during the driest, warmest January in 43 years.

- 23 February 2024

- 6 min read

- by Parvaiz Bhat

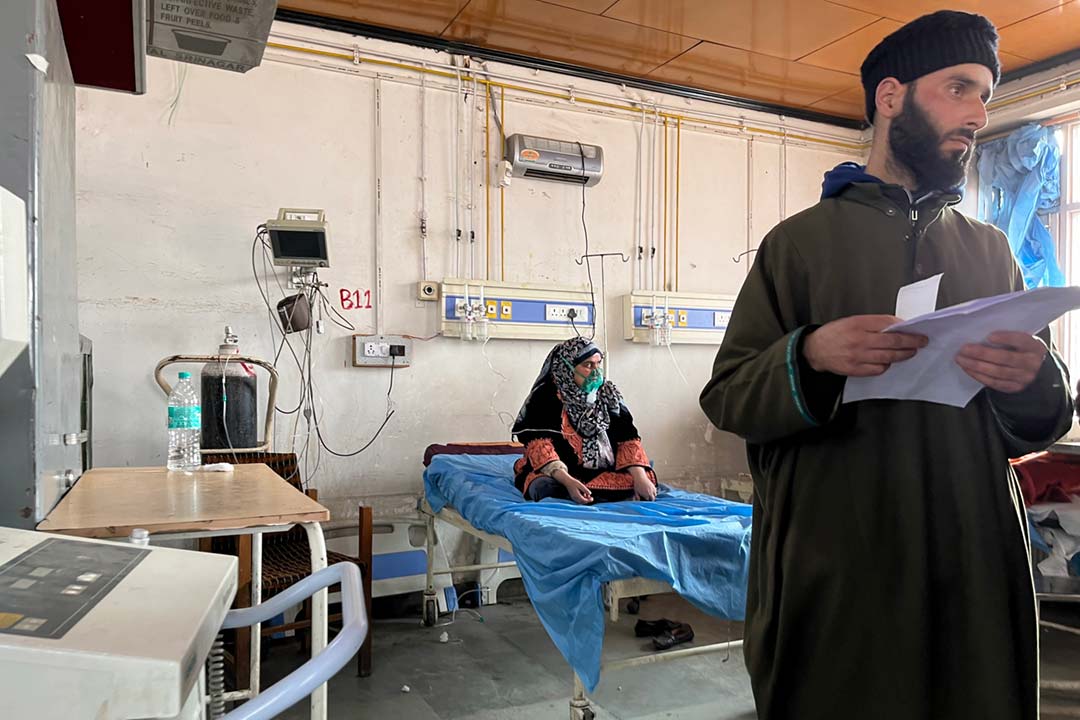

Three times in the last two months, Hajira Begam, 56, has needed to seek emergency care at Srinagar's Chest Diseases Hospital (CDH) in Kashmir.

"On all the three occasions, she complained of breathlessness, due to which we had to rush her to hospital," says her son, Rizwan. Begam has asthma, and rushed trips from her village in northern Kashmir's Baramullah district to CDH increase in frequency in winter – especially during winters as abnormally dry as this one.

“Given the frequency with which extreme weather events occur, climate change is manifesting itself so clearly.”

– Mukhtar Ahmad, head of Meteorlogical Dept, Kashmir Himalayas

Residents of the Himalayan valley have gazed fretfully at unseasonably snowless peaks during the coldest months of the season, as experts explain that the dry conditions mean that particulate pollution hangs in the air for longer – creating haze, and exacerbating symptoms in patients, like Begam, with respiratory conditions. Doctors say hospital wards have been filled to capacity, and as farmers worry for the harvest ahead, second-round health impacts are anticipated.

"Winter gave us the slip"

Locally known as Chilai Kallan, the period that runs from December 21 to January 31 is the harshest and snowiest season in the Kashmir Himalayas. But this winter, no snow or rain fell between late October 2023 until early February. January registered as the warmest and driest in 43 years across the mountainous territory of Jammu and Kashmir (J&;K).

"Our region is rapidly transforming itself from four seasons to two seasons," Nazir Lone, a shopkeeper in Srinagar quips. "Two years back, we had no spring season because of a long drought and this year the winter gave us the slip," he says.

Credit: Parvaiz Bhat

Indian meteorological department officials say that the precipitation deficit was pronounced this winter across the Indian Himalayan region, with the mountain states and union territories of Uttarakhand, J&;K and Himachal Pradesh recording deficits of -75 to -85 percent.

Though the drought ended early this month with a light snowfall, "Any snowfall after the main winter doesn't last [long enough to] ensure water in summer months for supporting agriculture, tourism and hydropower generation," says Mukhtar Ahmad, who heads the regional Meteorological Department in the Kashmir Himalayas.

According to Ahmad, the prolonged drought was a consequence of absence of a weather system known as the Western Disturbances, which originates from the Mediterranean and brings snow and rain to north India in typical years.

“It is a pity that we had no winter in Kashmir this year. Imagine what it means for our farms in summer."

– Mehraj-u-Din Mir, farmer, Tujjar village

Why exactly the Western Disturbances failed remains a matter of research, according to Ahmad, but it "looks like an impact of temperature variations due to climate change." The Hindu Kush Himalayan region is warming at a faster rate than the global average, according to the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD).

"Given the frequency with which extreme weather events occur, climate change is manifesting itself so clearly," says Ahmad. "In the past two decades, we have witnessed shorter winters most often, while this year the winter was totally dry. Droughts in summers have also become too frequent."

Poor harvests loom

Meantime, the dry spell has dampened the spirits of farmers as the new agricultural season draws closer.

"It is a pity that we had no winter in Kashmir this year. Imagine what it means for our farms in summer," says Mehraj-u-Din Mir, a farmer in Tujjar village near Sopore town.

Subsistence agriculturalists in the idyllic valley of Kashmir have traditionally relied on snow and glacial melt as well as rainfall to irrigate their farmlands, where they cultivate different crops such as rice, vegetables, maize and saffron.

Shakil Ahmad Romshoo, prominent scientist at Kashmir University's Earth Sciences Department, says that heavy snowfall in the coldest months – December and January – ensures creation of a large snowpack, which helps in maintaining freshwater supply in early summer in the form of snowmelt.

That droughts generally increase the risk of malnutrition in affected populations – with knock on impacts for immunity – is well-established. The scale of the impact of the current drought in Kashmir is yet to be seen, but Farhat Shaheen, an agricultural economist at Sher-e-Jashmir University of Science and Technology (SKUAST), says that during previous droughts of various severity, farmers have reported needing to sell off cows they couldn't afford to feed following crop failure. "It's a matter of research to what extent it would have impacted the nutritional status of a family who used to have cow milk at home, but had to sell it suddenly," Shaheen says.

Respiratory diseases

Meantime, in hospitals and health centres, the first-wave health impacts of this snowless winter are already in evidence.

"We have observed that patients suffering from bronchitis and asthma are at high risk of developing exacerbation because of poor air quality, while the number of chest diseases patients increases exponentially from November onwards in Kashmir, especially when the weather stays dry for longer durations," says Dr Naveed Nazir Shah, Head of Department at Srinagar's Chest Diseases Hospital.

Have you read?

According to Shah, pollutants linger in the air in dry weather and cause serious problems for people with respiratory diseases. "If there is snowfall, it clears the pollutants and people get relief from pollution-related problems," he says.

Romshoo confirms that the air quality of the Kashmir valley deteriorates significantly during winters, with the level of hazardous PM2.5 particles touching 350 μg/m3 against the national permissible limit of 60 μg/m3, as people burn biomass to keep warm.

“This winter, we had no beds to accommodate all the patients. There was a 40% increase in patient load.”

– Dr Naveed Nazir Shah, pulmonologist, Chest Diseases Hospital, Srinagar

"This winter, we had no beds to accommodate all the patients. There was a 40% increase in patient load ," Shah says, adding that most of the patients were elderly people, and this mostly happens during drought conditions in winters and springs when people are exposed to spring allergies.

No vaccine for climate change – but you can get a flu shot

Shah says that vaccines such as flu vaccines and pneumonia-blocking jabs like the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine have the potential to help reduce the patient load in hospitals, helping protect especially those people with low immunity.

And there are signs that message may be filtering through. Uptake of flu vaccines, which has been strikingly low in the past, may be rising, as doctors take to media channels to raise awareness, and as experience of swine flu and COVID-19 alter public attitudes. A pulmonologist, Zubair Saleem, wrote in a local daily in September last year that many of "my patients have been inquiring about the flu shot or influenza vaccine".

Mounting crisis

Evidence from elsewhere in the Himalayas points to potential future spikes in vector-borne illness too, as temperatures and weather patterns shift.

Nepal's unprecedented high-altitude dengue cases augur mounting risk from mosquito-transmitted illness, with a 2020 study in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health calling for research into the spatio-temporal distribution of both dengue and chikungunya in the Hindu Kush Himalaya.

Proposing adaptation and mitigation measures for human health in the Hindu Kush Himalayan region, another study highlights the risks climate change pose to safe drinking water, sufficient food, and secure shelter in the HKH region.