How vaccinating cows in Bangladesh curtailed a human anthrax outbreak

A combination of information, vaccination and timely treatment brought a post-monsoon outbreak of the potentially deadly zoonotic infection under control.

- 19 January 2026

- 4 min read

- by Mohammad Al Amin

In the first week of September, Fatema, wife of autorickshaw driver Billal Hossain of Nagarjitpur village in Rangpur district, cleaned and sliced up a piece of recently-butchered beef to cook. “After a few days, I saw some blister-like things were exposed on my hands and it was itchy. I got panicked and went to the doctor.”

She correctly suspected that the butchered cow had been sick with anthrax. Between July and September about 50 human cases of the zoonotic disease were reported in the district. Two other districts were also affected.

Anthrax is zoonotic, leaping from animals to humans, and many more animals than humans contracted the infection. At least seven cows in Nagarjitpur alone died with anthrax in that time period, according to locals, and several of Fatema’s neighbours had contracted the infection.

Mohammad Munnaf, 35, described experiencing “severe ache” from the blisters on his hands in August, after one of his cows was diagnosed with anthrax. Without proper care, anthrax can be fatal in humans, but like Fatema’s, Munnaf’s symptoms eased with treatment.

Outpatient care appears to have sufficed across the upazila. “No patient was admitted to hospital. The situation remains under control due to building awareness among people, and inoculating animals with anthrax vaccine,” Dr Muhammad Tanvir Hasnat, Health Officer at Pirgachha Upazila Health Complex, told VaccinesWork late last year. “We notified [the outbreak] to the higher authority and found no cases after September.”

Livestock and livelihoods

“A few sick cows were slaughtered and eaten by locals,” said Pirgachha Upazila Livestock Officer Dr Ekramul Hoque Mondol. “That's why the disease transmitted among people.”

He further explained that farmers have lack of awareness about the disease, and tend to slaughter cows that are showing signs of illness in order to recoup some of their losses. Shefali, the wife of another rickshaw driver from Nagarjitpur, buried the carcass of the cow she lost to anthrax deep underground on Livestock Department instructions. That was the safest course of action from a disease-spread point of view, but it amounted to a financial hit equivalent to 70 or 80,000 taka (about U$ 573–655).

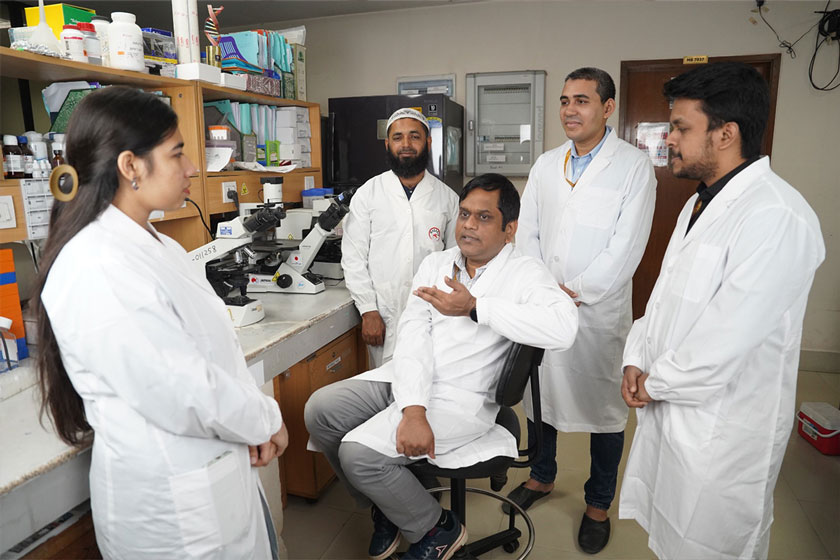

Dr Mondol said his department formed nine veterinary medical teams to test cows for anthrax in the villages and in ten slaughter houses, to make sure no contaminated meat wound up on the table. He said the nine teams also administered anthrax vaccine to animals, particularly cows. “If any animal is found with anthrax infection, then we are giving treatment to the sick animals with penicillin antibiotics injection.

“An animal needs around a week for recovery,” he explained. “After giving treatment, the animal can be slaughtered after 21 days. At the same time, we are also carrying out programmes including distributing leaflets among the villagers to build awareness about anthrax. However, so far we came to know that there was no previous history of anthrax infection in the upazila.”

Dr Abu Syed, District Livestock Officer for Rangpur, said veterinary teams vaccinated 485,800 cows in Rangpur between August and November 2025.

“If the anthrax vaccination rate reaches 50%, the [herd] immunity of the cattle will grow,” he added.

Zoonotic leap

Dr Ahmed Nawsher Alam, Principal Scientific Officer(PSO) at Department of Virology of Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research (IEDCR), tested samples of anthrax infection in human bodies from both Rangpur and Kushtia districts. “We have got cutaneous anthrax in Bangladesh. It is a bacterial disease. If anyone handles infected animal then the person usually is infected with the bacteria.”

Cutaneous or skin anthrax typically comes from contact with the mucus, saliva, blood, meat, bones, intestines, skin, or fur of infected cattle, he explained. Anthrax can also infect the gut, if contaminated food is eaten, or be injected. The most severe form of anthrax is inhalational – when the spores released by the bacterium are breathed in.

Have you read?

Prof. Dr. Mohammad Farhad Hussain, Director for Disease Control at the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS) told VaccinesWork that the tripartite attack – animal vaccination, human awareness-raising and timely treatment – had worked to bring the situation under control. But scientists warn anthrax is seasonal, and prone to returning after the rains.

“The outbreak happens from July till September,” Dr Hussain said. Anthrax spores can survive for a very long time in the ground. As weather patterns change and disturb soil ecology, the risk of the return of dormant anthrax in various parts of the world rises.