Kenya's protected generation: 25 years of Gavi impact

Twenty-five years of Gavi support are a lifetime for young mum Elizabeth Khayumbi and nurse Mercy Daisy Handa, both living in a future underwritten by immunisation.

- 20 June 2025

- 6 min read

- by Joyce Chimbi

Elizabeth Khayumbi and her six-month-old daughter, Jaisley, live on a farm in Kenya’s Rift Valley region, but they happened to be on a trip to Kibra, Nairobi, when Jaisley’s most recent vaccination date came up.

Khayumbi had no intention of postponing the child’s appointment. “Immunisation was a priority in my family,” said the 23-year-old first-time mum. “I was born in the hospital, and fully vaccinated. Jaisley has not missed a single dose even though we live 40 minutes away from the hospital and the queues can be so long because it’s a big hospital.”

So, in Kibra, Khayumbi picks up her baby and heads out to a public clinic. The capital’s streets are busy: boda-boda drivers beep their horns to tout for business, and Jaisley, used to the country quiet, laughs with joy. At the health centre, the little maternal and child health booklet Khayumbi has brought with her is all the documentation she needs to get Jaisley seen. The child scrunches up her face in displeasure on the weighing scales, but rests cheerfully in every unfamiliar pair of arms that Khayumbi hands her to.

“I know immunisation protects her, as I too was protected. Jaisley will receive the vaccines until the nurses say it is enough,” Khayumbi says.

Later, when Khayumbi tells her family that she has taken Jaisley to an immunisation clinic in Nairobi, they are surprised. It didn’t used to be so simple, says the grandmother with whom she lives in Njoro.

A lifetime, and the blink of an eye

Decades ago, hopping from one clinic to another was discouraged, Khayumbi hears. There were many fewer vaccines on offer, and those that existed, were in general harder to get hold of.

To Khayumbi, it might be a literal lifetime ago, but it wasn’t all that long back that only a minority of Kenyan children were able to get protected against vaccine-preventable diseases. A 1989 survey showed only 44% of Kenyan children had been fully vaccinated – the actual figure was likely much lower as immunisation data released before 2003 did not include the North Eastern region, and also missed out several northern districts in the Eastern and Rift Valley regions due to accessibility challenges.

Khayumbi’s grandmother says that in her own time, most babies were born at home, and children largely went without vaccination. The effects of that showed in the saddest of statistics. As recently as 2000 – the year that Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance was founded in a basement room in Geneva with a mission to make vaccination available to children in the world’s poorest countries – Kenya’s under-five mortality rate stood at 96 deaths per 1,000 live births.

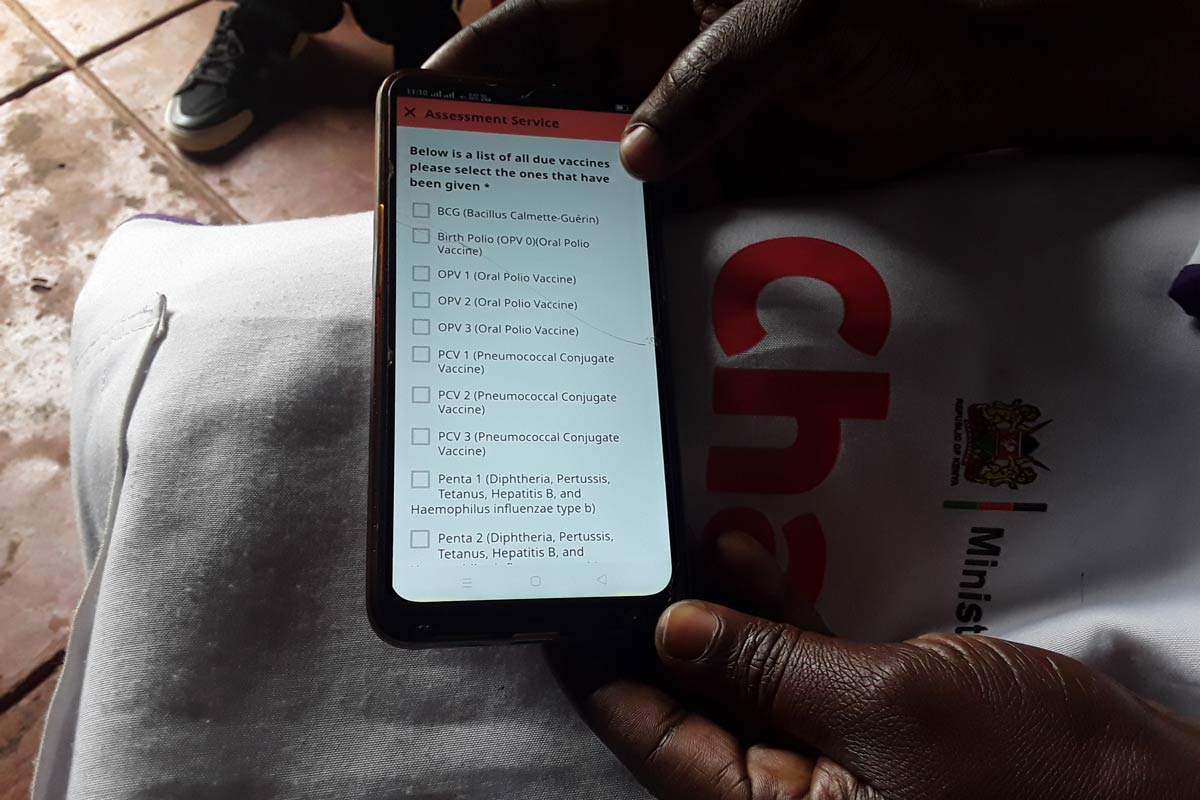

Today, vaccines are available in every corner of the country. Vaccine follow-up conducted by Community Health Promoters using the Gavi-supported eCHIS (electronic community health information system) have been the norm since 2023 – the same year that saw the national under-five mortality rate drop to an all-time low of 40 per 1,000 live births. Ninety-three percent of Kenyan children are fully immunised with the basic diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis vaccinations that are the conventional indicator for immunisation coverage in general.

Raising a culture of vaccination

Even in Khayumbi’s own infancy, getting a child protected was a notably more difficult task than it is today. She offers the example of vaccination cards: her mother’s generation, she says, had to “buy the immunisation cards at the hospital.” The prices were not high, but they were still more than many could afford. The consequence of that was vulnerability: “No card, no vaccine,” says Khayumbi. Though Khayumbi doesn’t know it, Gavi has since stepped in to contribute to the cost of the mother-child health booklets. What she does know, is what matters: “Today, the booklet is free.”

“We also have many more vaccines,” the new mother continues. “Years ago, mothers prioritised BCG and polio vaccine. People were very afraid of TB and polio, which was causing disability. Affected families were stigmatised and shunned by the village.” Today, with Gavi support, least 12 child vaccines are available as part of the public health system in Kenya, including HPV given at ten years, against cervical cancer.

Paying it forward

Registered clinical nursing officer Mercy Daisy Handa, also 23 years old, can confirm from her vantage point on the frontlines that Kenya has indeed come a long way in the quarter-century since the Government partnered with Gavi to provide more Kenyans with access to vaccination. At Mbagathi County Hospital, a level five county referral hospital in Nairobi, she serves a catchment population of more than a million people.

Born in Busia, western Kenya, to a large family of nine children helmed by a day-labourer father and a grocery-trader mother, Handa grew up protected: her parents “prioritised their children,” she says. She and all her siblings were born in hospital, and fully vaccinated.

But her own childhood memories tell her that wasn’t always the easiest road for a parent to walk. She remembers thinking of hospitals as places where sick people lay on the ground in the hot sun, waiting their turn to see the only doctor.

“Mothers waited all day for children to be vaccinated,” she says. “This is when my desire to be a health provider started, and it continued when my brother became one. I am motivated by a desire to change such childhood memories. I want every child to have a friendly and very pleasant hospital experience. Today, the immunisation landscape is thankfully much different, with numerous health benefits for both mother and child.”

Inflection point

Handa says Kenya’s transformative child vaccination journey took off in the early 2000s when the country began receiving a much-needed boost. Gavi has supported Kenya’s national immunisation programme since 2001, providing vaccines and related supplies and assistance worth more than US$ 940 million since. Over that time, Kenya, too, has been committing increasing amounts of domestic resources to a public health project that has proven its value.

Handa says veteran health providers have told her how they battled for decades to control a number of deadly and preventable diseases without access to preventive vaccines. But for many of these illnesses, that has since changed. Over the past two and a half decades, Kenya has introduced several new vaccines into its routine immunisation schedule.

They include the combo pentavalent vaccine against five diseases (diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, hepatitis B and Haemophilus influenza type b), which began to roll out in 2002. In 2011, Kenya became the first African country to roll out the pneumococcal vaccine (PCV10) against pneumonia, meningitis and sepsis with Gavi support.

A second dose of the measles vaccine introduced in 2013; the rotavirus vaccine against severe diarrhoea in 2014, and the inactivated polio vaccine in 2015. The introduction of the Hib vaccine in 2001, with Gavi support, resulted in an 89% reduction in Hib meningitis cases.

In 2019, Kenya became the third country to launch the malaria vaccine after Ghana and Malawi. In 2025, Gavi will support Kenya’s introduction of the typhoid conjugate vaccine (TCV) into the routine immunisation programme.

Have you read?

The next generation’s next generation

Handa says the new generation of health providers are entering a system with multiple new tools and multi-pronged strategies to beat back the risk of preventable diseases for the youngest and most vulnerable.

She nonetheless stresses that the disease landscape presents many emerging challenges as climate change and population movement introduce and re-introduce disease outbreaks.

More than half of outbreaks recorded in Kenya between 2007 and 2022, and analysed in a recent study of the diseases, were epidemic-prone. They included COVID-19, cholera, epidemic malaria, Rift Valley Fever, yellow fever and typhoid fever. Thirty-two percent of the diseases including hepatitis A, B, and E as well as pertussis (whooping cough) were diseases of public health importance.

In other words, there’s further to go. Health workers like Handa, protected in their turn by vaccination, are ready to take up the baton for the next leg.

More from Joyce Chimbi

Recommended for you