Mental health support for mothers improves child health in Kenya

Screening new mums for stress and depression is offering young women a lifeline - and helping to ensure more children are vaccinated.

- 27 August 2025

- 5 min read

- by Joyce Chimbi

Stigmatised and shamed for becoming pregnant at 17 years, Tess Wanja developed incapacitating bouts of anxiety and distress, as well as physical symptoms such as fatigue and shortness of breath. She stayed at home, avoiding antenatal clinics.

Her baby was delivered at home in 2023 by a traditional birth attendant in Mukuru Kwa Njenga, one of several villages that make up Mukuru – a densely populated informal settlement in Nairobi, home to an estimated 700,000 people.

As an ‘A’ student who turned from “a star to a failure overnight”, Wanja said she found pregnancy and motherhood stressful and difficult: “I struggled to prioritise, leading to prolonged delays in my child’s immunisation,” she said.

Perinatal mental health disorders – conditions shaped by biological, psychological and social factors – can distort emotions, thoughts and perceptions, with young women aged 18–23 up to ten times more likely to experience depressive symptoms than older mothers.

In Africa, adolescents and young women are disproportionately affected, largely due to poverty and weak healthcare systems. But the impact extends beyond the mothers themselves. Deteriorating mental health can lead to delayed or missed immunisations for their children, poor feeding practices, and reduced engagement with healthcare more broadly, said Steve Ochieng, a nursing officer at Mbagathi County hospital in Nairobi.

To counter these challenges, Kenya has integrated mental health care into maternal and child health services at the primary health care level in line with World Health Organization guidance.

Doing so has strengthened mental health care and closed service delivery gaps between the community and health facilities, said Ann Robbie, a Community Health Promoter (CHP) and Vice Chair of Lindi Community Health Unit in Nairobi.

“CHPs were formally integrated into the Ministry of Health in 2023. Today, all public health facilities have CHPs in their system,” Robbie said.

From stigma to support

In Kenya, more than 15% of girls aged 10–19 become pregnant, and about 43% of them develop depression. Adolescent mothers face heightened risks due to lack of family support, stigma, cultural and religious taboos around children born outside marriage, and shame.

At 22, Melody Adhiambo says stress, anxiety and fear of the future made it hard to follow medical advice or keep track of her child’s immunisation schedule. Mothers experiencing depression and anxiety often struggle to navigate the health system and forget health appointments, said Ochieng: “They are less likely to seek immunisation services if it involves queuing because they often seek to distance themselves from people, community and ultimately, the health system.”

Isolation is common, added Wanja, who said many young mothers also find it difficult to build supportive relationships. Globally, depression and anxiety are leading health complications in pregnancy, and the burden is often greater in poorer settings. A 2023 study in Kibra’s Kianda village – a poor area of Nairobi – found that the prevalence of depression among mothers with children under the age of five was 30.7%.

For such women, CHPs are often the first point of contact with the healthcare system.

A 'lifeline' for young mums

“Women’s mental health is assessed throughout the pregnancy and after delivery in the community and health facilities,” said Evalyne Ayuma, a CHP attached to the Lindi Beyond Zero Clinic in Nairobi. “After discharge following a delivery, CHPs are required to visit a mother within 48 hours to assess how they are coping, managing any stress and emotions. We make referrals for mental health support where necessary.”

In Adhiambo’s case, a CHP “befriended me from the moment she saw I was pregnant,” Adhiambo said. “I was ashamed, stressed and afraid of going to the clinic because the nurses are the same age as my mother, so she would come with me as my support system.”

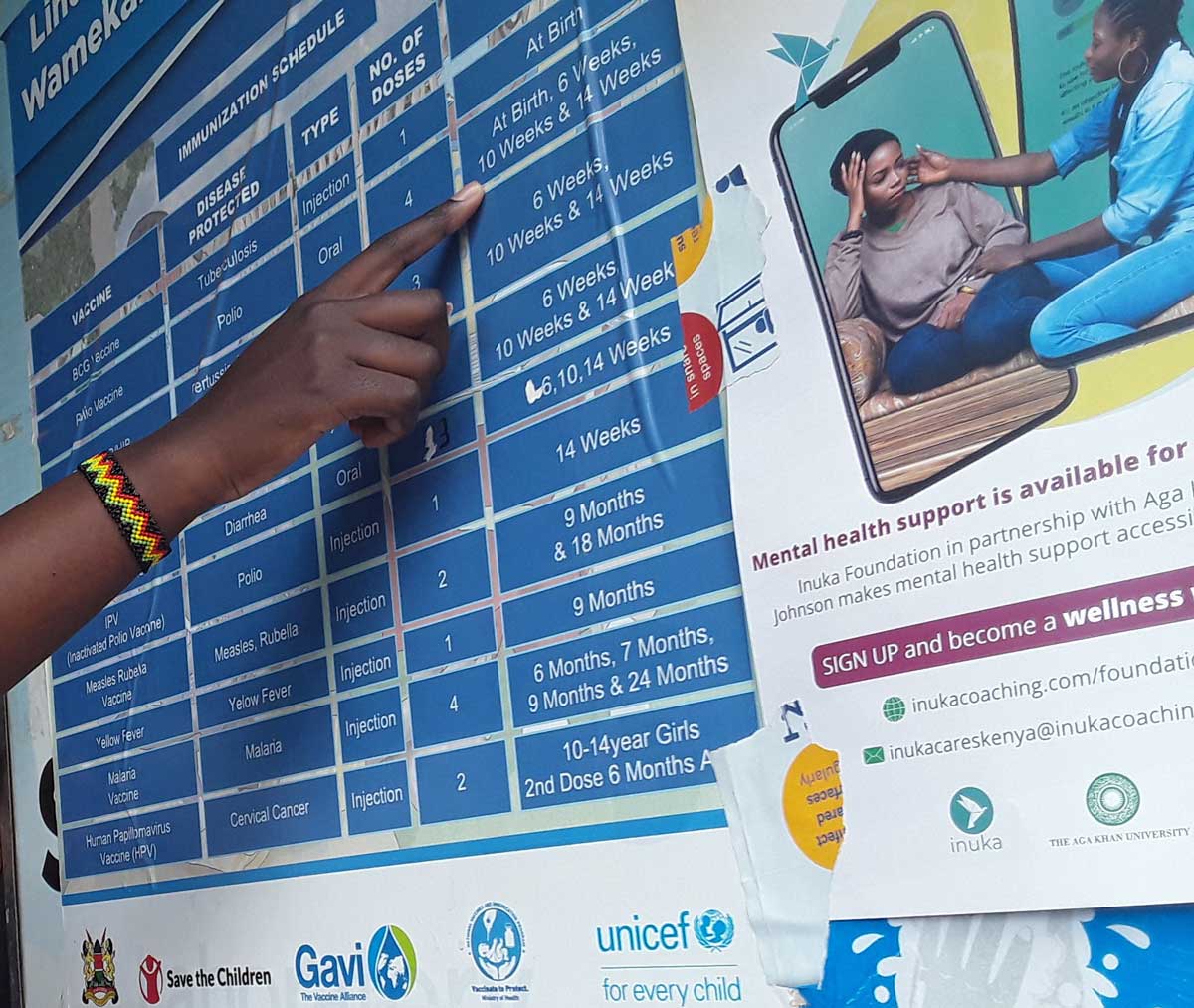

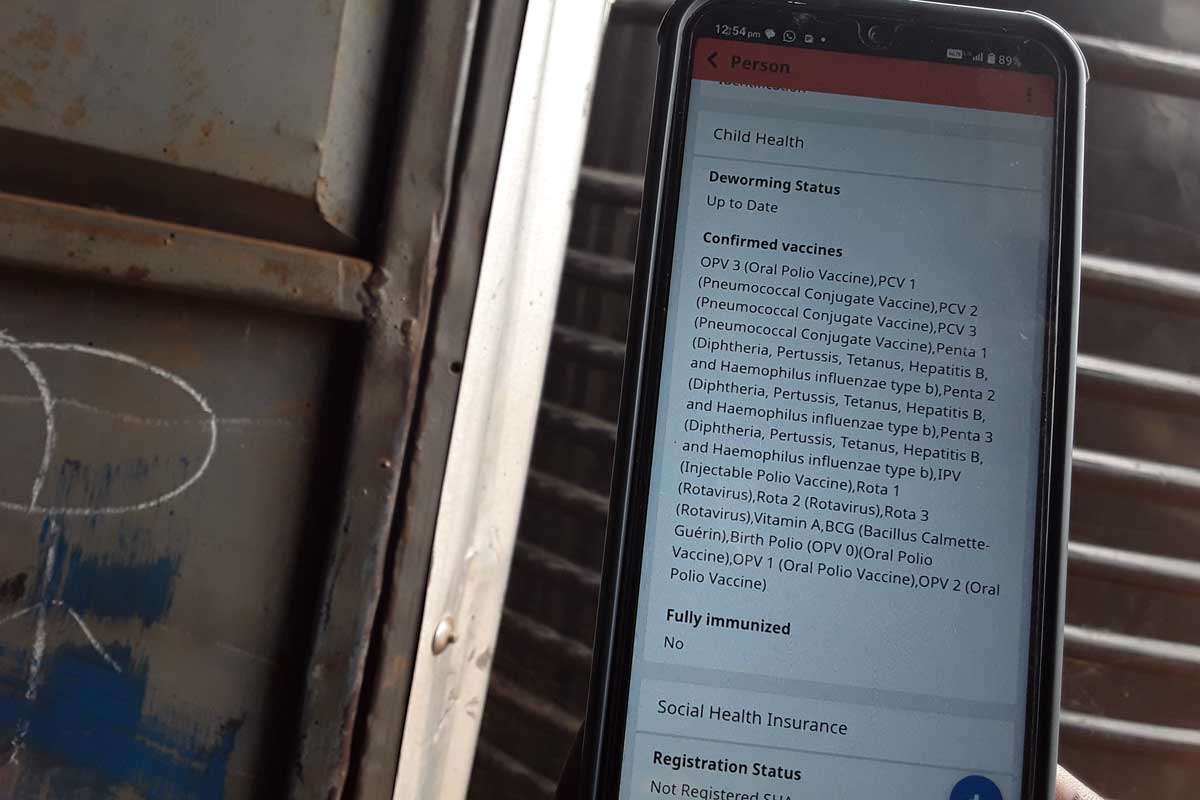

All CHPs are equipped with a smartphone with a mobile phone-based app called the Kenya Electronic Community Health Information System (eCHIS-Kenya) loaded onto it, which they use to manage their caseloads. “[The app] sends collected data directly to the health facilities we are linked to,” said Robbie.

CHPs, their managers, as well as national disease surveillance coordinators can also access this data to monitor health service delivery in the community. This is important, given the relatively high prevalence of mental health disorders among women of reproductive age.

“eCHIS gives you a complete health profile of an individual or household in a matter of minutes,” said Robbie. “Today, mental health screening at the household level is routine and especially for pregnant, breastfeeding mothers and, mothers whose children are less than five years.”

According to Nairobi City County, there are already 7,372 CHPs in the city, with some 107,000 nationwide. Together, they have registered some 8.57 million households in the eCHIS system, against a government target of 12 million. These workers have also provided post-registration services, including psychosocial support and tracking maternal and child vaccinations, to 7.33 million households so far.

Robbie explained that mental healthcare was about keeping both mother and baby connected to the health system as a gateway to receiving the full spectrum of health services – including full vaccination. “Maternal health services are not just about pregnancy, labour and delivery, it is also about the mind, and a mother’s ability to cope and care for the baby,” she said.

Listening to mothers’ experiences is a high priority. “At times that is all it takes to make a difference,” Robbie said.

CHPs also bring young pregnant mothers together, for peer mentorship and support. “We form and supervise the groups, but they run their own activities with guidance from peer mentors or mothers in the same group who have overcome mental health challenges that come with motherhood,” Ayuma said.

For Jasmine Atieno, the service has been a lifeline. Upon discovering she was pregnant in 2024, aged 19, “I did not want to be alive anymore,” she said. “Ayuma, the CHP in my area, visited me often and has ensured I keep all clinic appointments. She encouraged me to join a peer group. These days I am stress-free, and in training to become a professional nail specialist.”