Measles blindness: Habeeb’s story

Measles is not just deadly. Some of those who survive suffer severe, sometimes total, eye damage. VaccinesWork met one mother in Nigeria desperately trying to save her son’s sight.

- 22 December 2022

- 11 min read

- by Royal Ibeh , Maya Prabhu

Sikirat Sa'id's baby Habeeb was only six months old when her aging mother fell ill, and Sikirat was called away to Ilorin in western Nigeria to help. She packed a small bag, bundled Habeeb onto her back, and boarded the bus for the 300-plus kilometre journey from Lagos.

The small bag contained, among other important things, Habeeb's immunisation card. He hadn't yet missed a single vaccine, and Sikirat didn't want this trip to knock him needlessly off schedule.

“Hearing the doctors saying that my son won’t be able to see made me so sad. I started crying, and no-one was able to comfort me at that moment. I just kept blaming myself. Just one mistake I made has cost my son his eyes.”

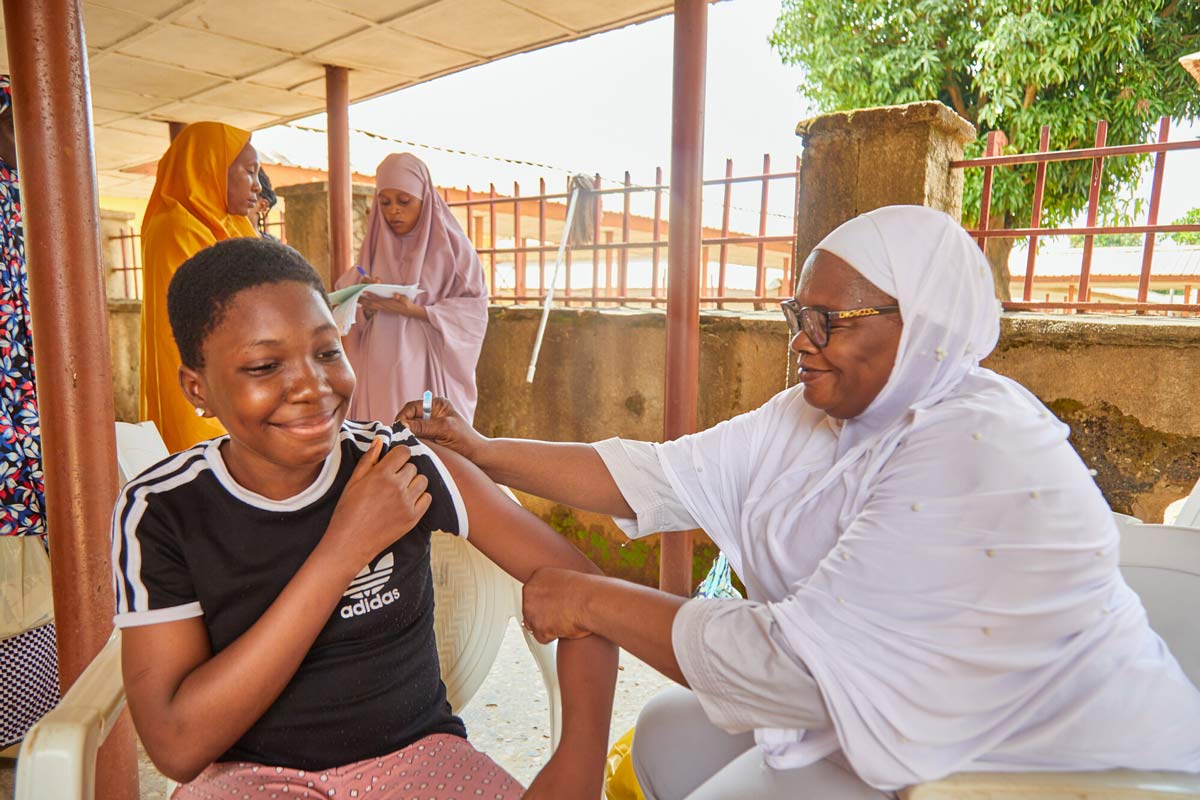

"When it was his next immunisation day, I took him to a health centre at Ilorin, but they told me that they don't have the vaccine," she recalls. "They gave me another date to come. I went to the hospital on the appointed day, but they told me they still don't have the measles vaccine, so I gave up."

Months passed; the grandmother died. Sikirat and Habeeb, now ten months old, returned home to Lagos, and paid a visit to their local clinic. It was late-middle 2012, the ebb-tide of an intense rainy season. "I still remember how angry the nurses were. They were so angry with me that I missed the measles vaccine. They told me that it was too late to give him – that was how my son ended up not taking the measles vaccine," Sikirat says.

It isn't clear why the nurses at the Lagos health centre told Sikirat that it was "too late" to administer the jab to the boy. Nigeria's health system specifies that the two-dose measles vaccine ideally be given at nine months and fifteen months – but catch-up vaccination is recommended for any child up to the age of fifteen years of age who has missed one or both doses. The confusion would have terrible consequences for Habeeb.

Less than a year later he got sick – boiling with fever, mottled with an all-over body rash, eyes sore and glued shut with discharge.

Inflammation of the conjunctiva and the cornea are common with measles, making the eyes red and sore, and sensitive to light. Most often, the inflammation resolves without lasting damage. Sometimes, however, especially when a child has low levels of vitamin A as a consequence of poor nutrition, or when bacterial or viral coinfection sets in, ulceration of the cornea can lead to permanent scarring. In the severest cases, a process called keratomalacia can occur, in which the cornea melts, and the contents of the eye fall out. In many cases, keratomalacia precedes death.

Sikirat took her son to Alimosho General Hospital in Lagos. From there, Habeeb was transferred to the Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH), and then transferred again to the Lagos State University Teaching Hospital (LASUTH). When his eyes opened slightly, Sikirat says, she saw that "they were very red".

If anything, it was worse than it looked. "The doctors told us that he won't be able to see with the eyes, as the measles has affected his two eyes," Sikirat recalls.

"Hearing the doctors saying that my son won't be able to see made me so sad. I started crying, and no one was able to comfort me at that moment. I just kept blaming myself. Just one mistake I made has cost my son his eyes."

Resurgent danger

As recently as 2004, measles and vitamin A deficiency were understood to be the leading cause of blindness in children in developing countries. Those two conditions are linked. Vitamin A deficiency is dangerous to the eye, drying it out, potentially damaging both retina and cornea; it's often infection with the measles virus – which, on its own, can threaten parts of the eye – that causes vitamin A levels to tank from borderline levels into catastrophe.

Measles – the most contagious of the vaccine-preventable diseases, known among epidemiologists as the ‘canary in the coalmine’ for its ability to mark out weak health systems – is making a comeback. In the year to April 2022, Nigeria alone reported 12,241 measles cases.

Estimates of global incidence through the 1990s and early 2000s ranged widely – from 15,000 new cases of measles-linked blindness a year to 100,000 cases a year. Better measles vaccination coverage and better vitamin A supplementation have since driven down those rates.

But in places where vaccination coverage is spotty, and particularly where good nutrition is also hard to come by, children remain at serious risk.

Alarmingly, it's becoming clear that since COVID-19 disrupted lives and health systems all over the world, those zones of vulnerability have grown. Nearly 40 million children worldwide missed a measles vaccine dose in 2021 – a record hole in the collective safety net of herd immunity.

Now measles – the most contagious of the vaccine-preventable diseases, known among epidemiologists as the 'canary in the coalmine' for its ability to mark out weak health systems – is making a comeback. In the year to April 2022, Nigeria alone reported 12,241 measles cases.

It's unknown how many of those cases have cost a child their eyesight. But when we spoke to Dr Dupe Ademola-Popoola, paediatric ophthalmologist and Professor of Ophthalmology at the University of Ilorin, she described at least one: a baby girl, who arrived at the hospital already suffering measles-precipitated keratomalacia.

"If [patients] come early, we can hopefully quickly keep the cornea well – healthy. You know the dry cornea can be taken care of at the outset," Dr Ademola-Popoola explained. The eye can be kept clean and moisturised, antibiotics can be administered to stave off the secondary infections that are liable to provoke scarring, and the administration of adequate doses of supplemental vitamin A will be ensured. The goal is to save at least 50% of the cornea – if more than that is lost, the child will typically need a place at a special-needs school, and those are scarce.

Watching his favourite cartoon, Ben 10, or playing Ludo with his sisters tires the eye; he can only keep it up for so long. Playing football with his friends puts it at risk of injury. “The doctor told me to be careful, so I am careful,” he says.

"Once we lose that stage [for early intervention], it's really difficult, once there has been ulceration. In the child in question, the ocular contents were already pushing out."

At five months, she was still too young for her first measles vaccination, meaning she was reliant on high vaccination rates in the community for protection. That collective shield had let her down.

"The parents thought it was malaria initially," Dr Ademola-Popoola says. But soon, there were skin rashes, the child's mother reported, and then her daughter's eyes became "matted" – gummed closed. "Before she could say Jack Robinson, the cornea started melting," says the doctor.

Have you read?

Sadly, the baby died soon later. But even among children who survive the acute, initial sickness of a blinding infection, survival can be a highly qualified term. Research suggests that as many as 60% of children who go blind from any cause in developing countries will die within two years. "Some of them die from the same problem [that blinded them], or they die from neglect, or just because their parents cannot cope," Dr Ademola-Popoola explains.

For many of the remaining 40% percent, the future narrows drastically. An estimated 90% of blind children never go to school.

Habeeb at a crossroads

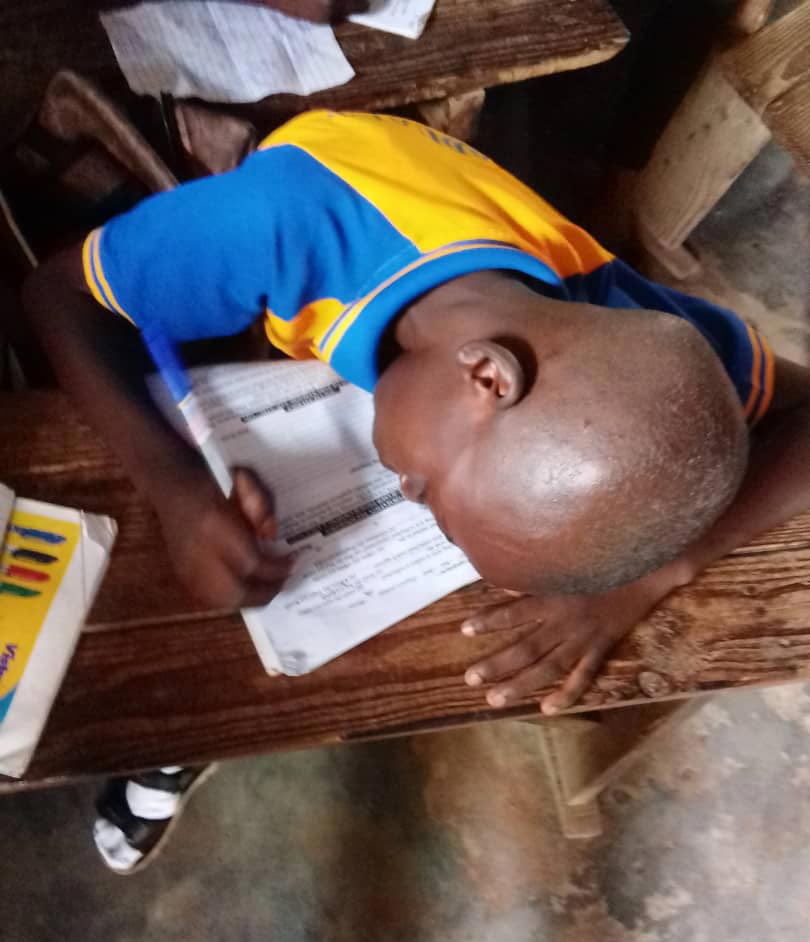

Habeeb Sa'id turned 11 in October this year and prayed to Allah for clear vision – at least in his better eye.

Credit: Royal Ibeh

He is small for his age and soft-spoken. He moves slowly and deliberately by both habit and necessity. He is protective of his independence. Offer to hold his hand to help him navigate a public space, for instance, and he'll politely turn you down. He hasn't accepted his parents' help at bath-time since he was seven, he tells VaccinesWork. "I do literally everything myself, however, with struggle," he says.

He is not blind – not quite. The right eye is hopelessly sightless: the cornea is damaged but, more decisively, the optic nerve is wrecked. The left eye, however, while cloudy with corneal scarring, retains an estimated 20% of full vision.

Sikirat has never stopped seeking out expert help for her son, which is why Dr Faderin counts Habeeb among the three children she is currently hoping to help access a corneal transplant.

Through this diminished aperture of sight, the world appears, according to Habeeb, not blurry, but "faint". He turns his head at angles to the object he's looking at, lays his left cheek almost parallel to the page he's reading: "If I move my eye somehow, it makes me see things more clearly." He is grateful to Allah, he says, for allowing him to see this much.

Still, the difficulty of sight dogs him and limits him. Watching his favourite cartoon, Ben 10, or playing Ludo with his sisters tires the eye; he can only keep it up for so long. Playing football with his friends puts it at risk of injury. "The doctor told me to be careful, so I am careful," he says.

"It becomes more difficult when I am reading, because water will start coming out of the eye freely if I strain it too much. So I try to read few hours – and I must read every day so that I can pass my exams," Habeeb says. Despite his visual impairment, he's at a regular school: "I compete in class with children who can see and read with their two eyes," he says. He's a good student: happiest in Maths and English, but excellent, his family reports candidly, in every subject. He likes his teachers, and they like him. One day, he intends to become a professor.

But right now, Habeeb's future is forking ahead of him. One road ends in the dark, literally: doctors worry that that a cataract in that better left eye threatens what remains of his vision.

The other fork leads towards an inarguably easier life. The eye specialists have identified the same better, imperfect eye as a candidate for a surgery that could restore up to 80% of its vision. This track, however, is littered with hurdles.

A donated second chance?

Dr Mosunmade Faderin, Medical Director at the Eye Bank for Restoring Sight, which has premises on the campus of LASUTH in Lagos, has met "many" children who are blind as a consequence of measles, though she is reluctant to specify a number off the top of her head.

Often, she explains, their loss of vision is tragic more than once over – preventable in the first place by vaccination, and again by proper care. The scarring that permanently ruins vision is frequently precipitated, she says, when a sick child's worried parents apply traditional, non-scientific remedies – "breast milk, and other things" – to the inflamed eyes, rather than seeking professional medical help.

That's, of course, not the story behind Habeeb's loss of vision. Sikirat has never stopped seeking out expert help for her son, which is why Dr Faderin counts Habeeb among the three children she is currently hoping to help access a corneal transplant.

"Both eyes were affected as a result of measles," Dr Faderin says, summarising Habeeb's case. "The right eye was more severe – hence the reason he can't see with it. For the left eye, the cornea was partially affected, hence the reason he can partially see with it. From our diagnosis, we think he can benefit from a penetrating keratoplasty."

The rate of success would depend on a few factors, including the size the adherence of the iris to the cornea, but it's reasonable to hope for 80% vision in that eye, she says.

Outcome aside, undergoing such an operation would put Habeeb in a small minority. Corneal transplantation surgery is in a "premature phase of development" in Nigeria, according to Dr Ademola-Popoola, and as such, operations like these are far from common.

One limiting factor, Dr Faderin explains, is cultural. "People die every day in Nigeria, yet the families of the deceased won't allow us to collect the cornea, due to cultural and religious beliefs. To them, if they donate their eyes to us, what will they use to see when they are resurrected?" she says.

That local scarcity makes the surgery much more expensive. If a suitable cornea was to be donated in Nigeria, "Habeeb will only have to pay for the surgery, which is like 500,000 naira (US$ 1,121)". As it is, the estimated cost for the procedure is double that – about US$ 2,500. That price tag doesn't reflect the cost of purchasing a cornea: "It cannot be sold," Faderin emphasises – but of facilitating its transfer from the donor to Nigeria.

In either case, it's too much money. The surgery could have been done in 2019 – a donor cornea was available – but Habeeb's family simply couldn't afford it. Meantime, the clock is ticking. Should Habeeb's eye deteriorate further, says the Dr Faderin, the odds of a successful transplant will diminish. Sikirat sounds resigned. "The only thing I can give him now is my unconditional love and care – and the best education as well."