What happens when you don’t recover from the measles

In public health, we talk a lot about mortality and survival rates. But tallying who dies and who lives is a far-too-simple binary. The consequences of a disease often outlast the infection. This is the first instalment in a new series we’re calling The Long Tail.

- 22 December 2022

- 7 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

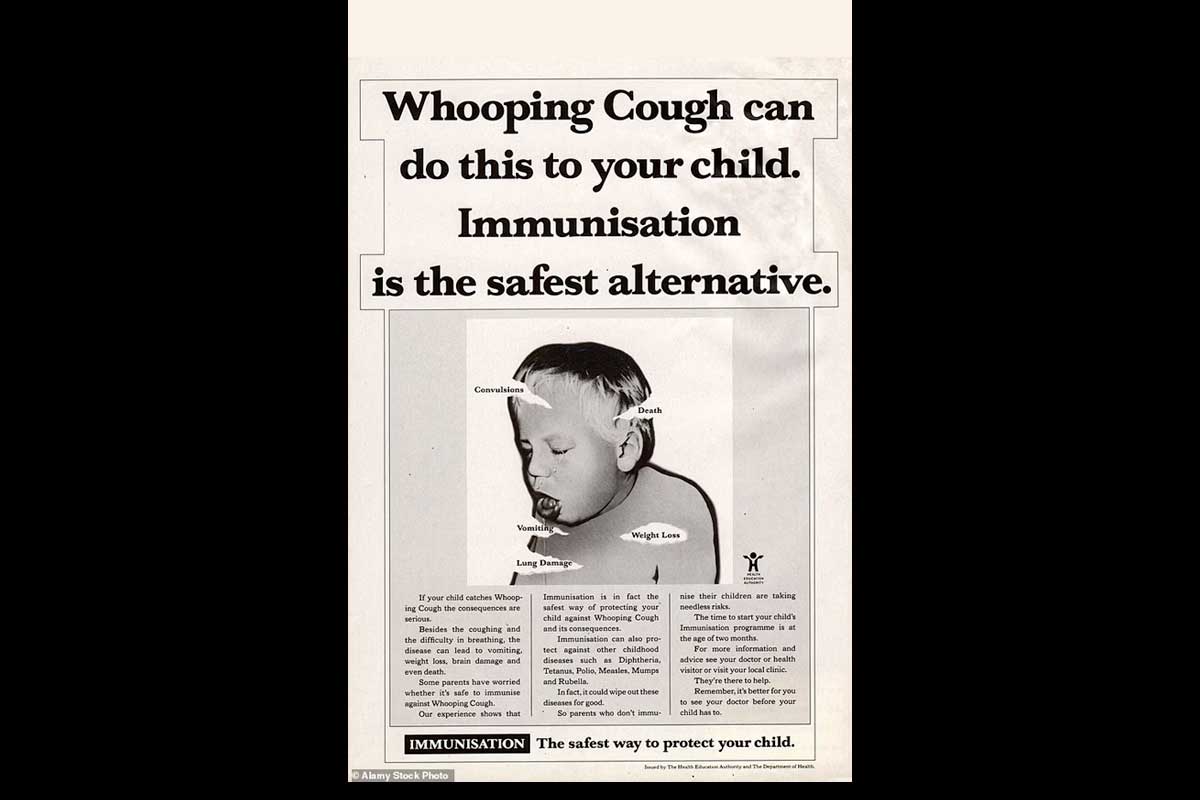

Measles – one of the most contagious human pathogens known to science – can kill you. That's worth stating plainly.

Overall, between one and three measles-infected, unvaccinated children in a thousand are expected to die, but the mortality rate is highly dependent on the conditions of a given person's life and health before they get sick.

As recently as 1990, measles and vitamin A deficiency were considered the major cause of childhood blindness in most lower-income countries. In 2004, WHO estimated that some 100,000 children lost their vision each year as a consequence of the virus.

As disease control expert Dr Peter Strebel explained to VaccinesWork earlier this year, amid poverty – which often brings with it poorer nutritional statuses and domestic overcrowding – outcomes skew far worse. In circumstances like these,as well as in humanitarian emergencies, the virus is anticipated to claim as many as 15% of its victims.

Everyone who doesn't die (by definition) survives their infection. But survival doesn't always mean a return to full health. A proportion of measles survivors live on with permanent, life-changing disabilities. A very small, unlucky minority will die, years after the initial brush with the sickness, of a rare, sudden-onset, degenerative brain condition. A majority will be left more vulnerable to other illnesses following their tussle with the virus, a consequence of a measles-linked phenomenon called 'immune amnesia', and a significant epidemiological risk factor at the population level.

How the virus invades

Someone is sick with measles. They cough, emitting viral matter into the air as aerosolised droplets, which remain airborne for as long as two hours. An unvaccinated, immune-naive person inhales those droplets, drawing them into their respiratory system.

The virus first infects immune cells in the lining of the lungs. Those infected cells travel to the lymph nodes where the virus transfers to other immune cells – the ones responsible for making antibodies that remember past pathogens. It commandeers those cells' machinery, using them to replicate at speed. Now the measles virus goes systemic, spreading aggressively through the body.

Speaking to Wired, Mayo Clinic molecular biologist Roberto Cattaneo estimated that only about a week after breathing in the measles droplets, some 50% of the body's memory cells are infected, seriously knocking the sick person's defences against other bacteria and viruses. Death with measles is often related to coinfection with other microbes, most commonly via measles-associated pneumonia.

The virus spreads in the trachea, killing some cells, which, as they shed into the airway, induce a cough – flinging virus-laden droplets out into the world.

Travelling in the blood, the virus infects capillaries in the epithelial cells, triggering the immune system to release chemicals that attack the invaders – but also damage host cells. The tell-tale measles rash on the skin is the visible upshot.

By a similar process, in the eye, it causes conjunctivitis – an inflammation of the conjunctiva, a blood-vessel rich membrane. Less commonly, the cornea can also be infected in a process called keratitis.

In about one in a thousand cases, the virus crosses into the brain where it can cause a dangerous inflammation of the brain parenchyma, or tissue.

Going blind

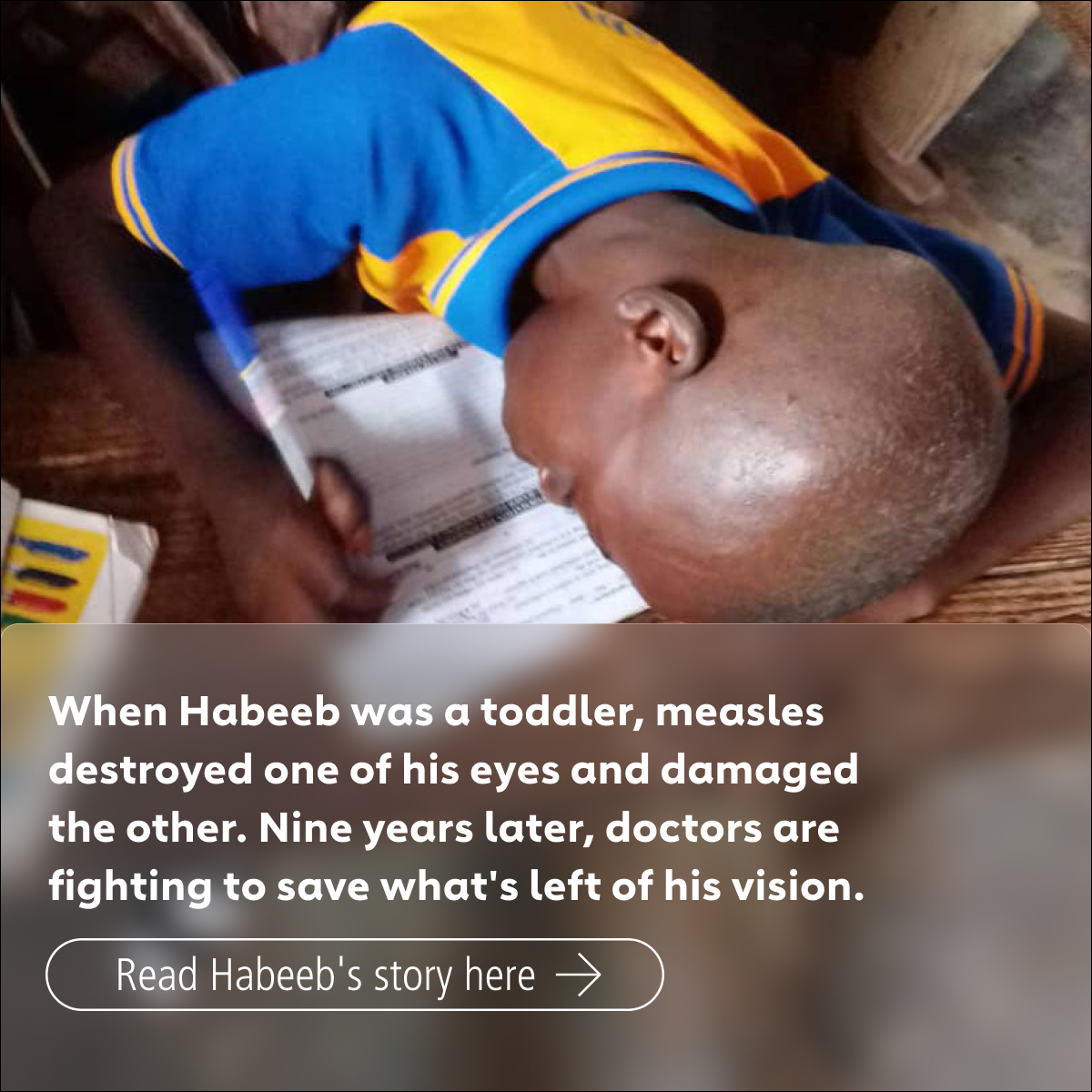

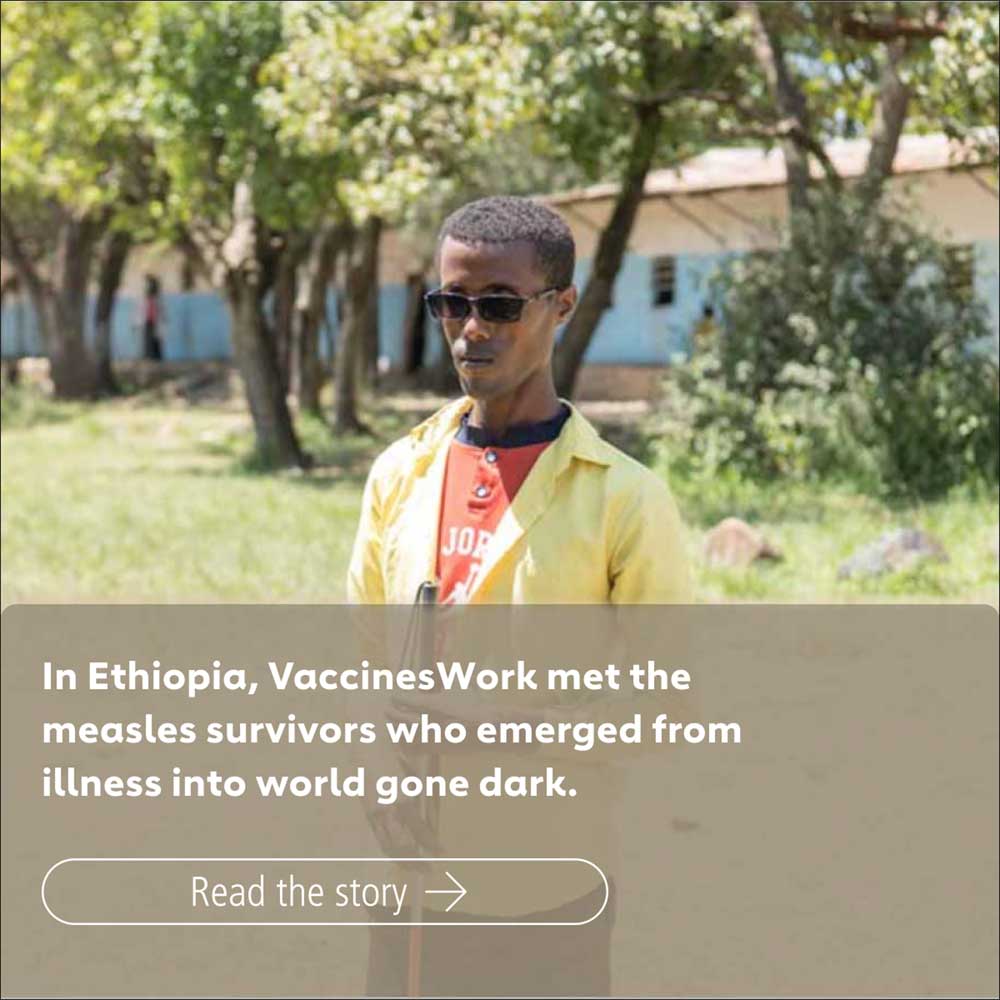

As recently as 1990, measles and vitamin A deficiency were considered the major cause of childhood blindness in most lower-income countries. In 2004, WHO estimated that some 100,000 children lost their vision each year as a consequence of the virus. Vaccination and supplemental vitamin A have helped – but the risk of this life-altering disability remains serious in communities with vitamin A deficiencyand low rates of immunisation.

“In a way, infection of the measles virus basically sets the immune system to default mode.” The body permanently ‘forgets’ how to fight off familiar pathogens. It can learn again – but learning means surviving a new infection, another threat – potentially, at population level, surviving another epidemic.

Measles can cause the epithelium of the cornea to ulcerate, leaving the eye vulnerable to bacterial infection – and the secondary infection can cause the cornea to scar, damaging a child's eyesight partially or completely. If a healthy cornea is as transparent as a window-pane, a scarred cornea is like frosted glass. Tragically, corneal scarring is often caused or exacerbated by misguided, unscientific attempts to treat or soothe the uncomfortable eye inflammation that is common with measles.

The risk to a child's eyes is particularly grave if, as a consequence of an inadequately nutritious diet, the child is low in vitamin A. When measles infects the lining of the gut, it can cause a loss of the proteins that carry vitamin A around the body – meaning an already vulnerable child's vitamin A levels can tank.

"If a child becomes acutely, severely deficient, the cornea can just melt," ophthalmologist and professor of international eye health Dr Clare Gilbert told VaccinesWork. Following a liquefactive necrotic process in the cornea, the contents of the eye can come out: "and that's a complete catastrophe," Gilbert says. "They end up permanently, totally blind after that."

Hearing loss

There are two routes by which measles can precipitate hearing loss: the first via ear infections, which are common with measles, though not often permanently damaging. The second is due to injury resulting from measles-related brain inflammation, or encephalitis.

Have you read?

Since measles-related hearing loss mostly affects children aged under five, it's liable to have considerable developmental consequences, potentially affecting speech acquisition.

According to a 2021 paper from Nigeria, measles-induced hearing loss is largely underreported, meaning it's hard to say for certain how common it is. Estimates suggest that before vaccination was widespread in the US, some 5-10% of cases of profound hearing loss were measles-linked.

Other lasting neurological deficits, from paraplegia to intellectual disability

Beyond deafness, encephalitis can cause other forms of lasting disability. The fatality rate with measles-linked encephalitis is about 10-15%. Approximately 25% of the people who survive measles-related encephalitis will suffer permanent neurological damage, ranging from motor deficits like paraplegia, to seizure disorders, and deafness, to intellectual disability.

Delayed death: subacute sclerosing panencephalitis

Sometimes years go by before the measles virus does its worst.

More common in poor countries than wealthy ones, sub-acute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is nevertheless extremely rare, hitting about 4-11 people per 100,000 measles infections.

SSPE is a disease that trails the primary measles infection by years. Typically, the patient has contracted measles at a young age – normally in infancy – and appeared to clear the infection. But a particular mutant of the virus has persisted, latent in the brain.

Much later, typically when the patient is aged between five and fifteen years, they begin to change. At first, the change is vague, hard to pin down – headaches, forgetfulness, mood swings, slipping grades in school. In time, though, there will be muscle spasms, speech loss, trouble walking. Within usually one to three years of diagnosis, the patient will enter a vegetative state, and then die. Nothing can be done to change the illness's course once it begins – but measles vaccination is a reliable preventive.

Immune amnesia

Not rare, and therefore dangerous at potentially great scale, is a phenomenon called measles-mediated immune amnesia. Not only does the measles virus's assault on the immune system make the body vulnerable to other bacteria and viruses during the course of the infection, but it can strip away previously acquired immunity to other pathogens, leaving people at higher risk of other diseases, even after they've cleared the measles virus from their systems.

In a landmark 2019 study published in Science, Harvard's Michael J Mina and his co-authors found that "measles caused elimination of 11 to 73% of the antibody repertoire across individuals … Notably, these immune system effects were not observed in infants vaccinated against MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella)."

Credit: Gavi/2021/Asad Zaidi

"In a way, infection of the measles virus basically sets the immune system to default mode," Mansour Haeryfar, professor of immunology at Canada's Western University, told the BBC. The body permanently 'forgets' how to fight off familiar pathogens. It can learn again – but learning means surviving a new infection, another threat – potentially, at population level, surviving another epidemic.

The good news

We have a vaccine, and it's really, really good.

More from Maya Prabhu

Recommended for you