Oral Cholera Vaccine saving lives in South Sudan

While South Sudan has been declared cholera-free, it is an ongoing battle to keep things that way.

- 23 December 2021

- 4 min read

- by Winnie Cirino

In 2016, conflict broke out in South Sudan, forcing many people to flee their homes. One of the people displaced was 38-year-old Ajang Ruben, who found refuge at Mingkaman camp.

In the same year, the government announced that there were cholera outbreaks in parts of the country, including Mingkaman where Ruben was living. “It was really congested and, eventually, there was an outbreak in the camp. It worried me because I didn’t know who would be next – me, my neighbour?” Ruben says.

“We have not heard of any cases since 2017, which I believe demonstrates how effective the vaccination drive and the vaccine have been.”

Seeing so many victims dealing with symptoms like vomiting and diarrhoea being admitted to the health facilities also made him anxious.

In 2017, South Sudan recorded over 16,000 cases of cholera, the highest in South Sudan’s history. Prior to that, between 2014 and 2016, 12,000 cases a year were reported. The true figures were likely much higher.

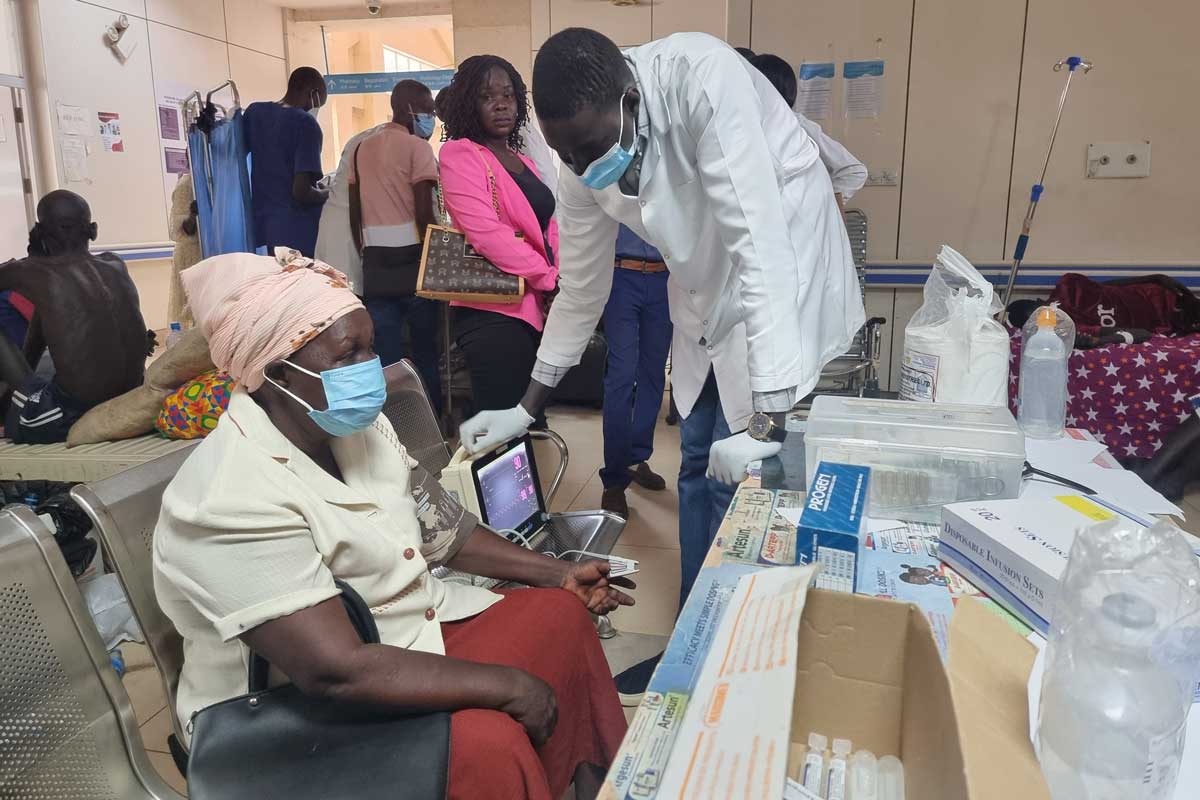

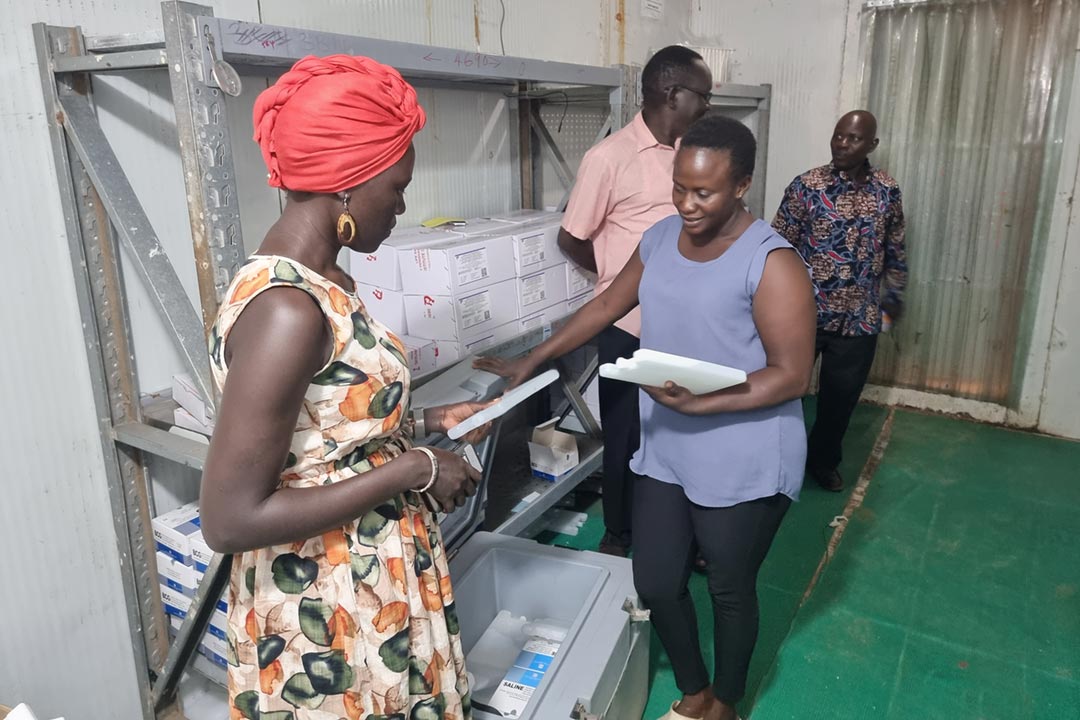

In 2017 South Sudan received more than two million doses of Oral Cholera Vaccine (OCV). The government ensured that Mingkaman received doses. Before the vaccines were administered, health workers created awareness in the community. They were the first to be vaccinated to show that the vaccine was not harmful.

By Diana Gorter

“They gave booklets showing people who have received the vaccine in other parts of the world including Africa,” Ruben says. “They said that this drug had been used before and it had helped a lot, especially for people in refugee camps. I reasoned if it was effective for them, it would be effective to us in Mingkaman and so I went for the vaccination to protect myself from cholera.”

He attests to how the vaccine saved his community, saying “since the initiative to bring in the cholera vaccines, all of us in Mingkaman have been fine.”

Have you read?

Jacob Buol Kuol was one of the vaccinators in Mingkaman. He says, “Many people came for the vaccine because they knew of the importance. We went to the radio stations and into the community to explain how the vaccine would help them and most were happy to be vaccinated.”

For those who were hesitant, the vaccinators served as examples. Kuol says, “Some people were afraid that we were poisoning them, but we told them that we had also been vaccinated and we were alive and fine. It helped convince people to accept the vaccine.”

He says he also often visited the hospital wards with cholera victims to encourage both those who were sick and their relatives. As a result, Kuol says, “There was no more death due to cholera since 2017, after many people took the vaccine in Mingkaman.”

Emma Symons, Emergency Response Team Health Project Manager of the international humanitarian organisation, MEDAIR, says the organisation has managed to vaccinate over 300,000 people in different parts of the country since 2017.

By Diana Gorter

She says it was difficult for vaccinators to reach some areas like Leer county due to insecurity and difficulty in access, but they worked with the UN Humanitarian Air Service to reach certain locations. In other areas, they piggy-backed on a United Nation’s World Food Program (WFP) drive where people are required to go to a central location to be registered to receive food parcels.

“When people see the impact of cholera on their community, it increases their willingness to come and be vaccinated. It also depends on the commitment of the local vaccination teams and whether they are willing to go to each and every area to reach the community,” Symons says.

She says they have continued with the OCV vaccinations in some areas, not because there was an outbreak, but due to their vulnerabilities.

“There have been outbreaks in neighbouring countries. MEDAIR conducted an OCV campaign in Rek in 2019-2020 as a preventative measure due to an outbreak in Sudan, and in Pibor earlier this year due to an outbreak in Ethiopia. Both of these areas are close to the border and are, therefore, at high risk,” Symons explains.

She says that South Sudan has been cholera-free since 2017 but, given that one dose of Oral Cholera Vaccine gives protection for one year, and two doses give protection for three years, it is necessary to administer further doses of OCV in high risk areas, and to remain vigilant with cholera testing and surveillance.

“We have not heard of any cases since 2017, which I believe demonstrates how effective the vaccination drive and the vaccine have been. However, even though there have not been any cases reported, we cannot say that cholera is eradicated from South Sudan forever,” Symons says.

She concludes by saying that there is always a risk of cholera returning because “most of the underlying risk factors have still not been addressed and most people in South Sudan still do not have access to clean water.”

More from Winnie Cirino

Recommended for you