Vaccine profiles: Cholera

The world has been in a cholera pandemic since 1961. Now that the disease is entrenched in so many regions, ensuring access to the vaccine is more important than ever.

- 2 May 2022

- 5 min read

- by Priya Joi

As the world scrambles to end the COVID-19 pandemic, we have actually been in an ongoing cholera pandemic for over half a century – the seventh in the past 200 years. In a previous pandemic, in 1832, the New York City Board of Health published a notice with advice on preventing cholera. “Be temperate in eating and drinking” it said, “Avoid raw vegetables and unripe fruit!”

Mass vaccination campaigns can be very effective in outbreaks such as those that occur in humanitarian settings. South Sudan was declared cholera-free in December 2021 after years of continuous transmission. A long-term sustained effort, including the rolling out of reactive and preventive vaccination campaigns to achieve cholera control, helped turn the tide against the disease.

The disease could kill people within hours. Desperation to find a cure probably explains the use of dangerous chemicals to try and treat it – including laudanum (morphine), mercury as a binding laxative and camphor as an anesthetic. These would often have done more harm than good, but some went to even further extremes, using opium suppositories and tobacco enemas.

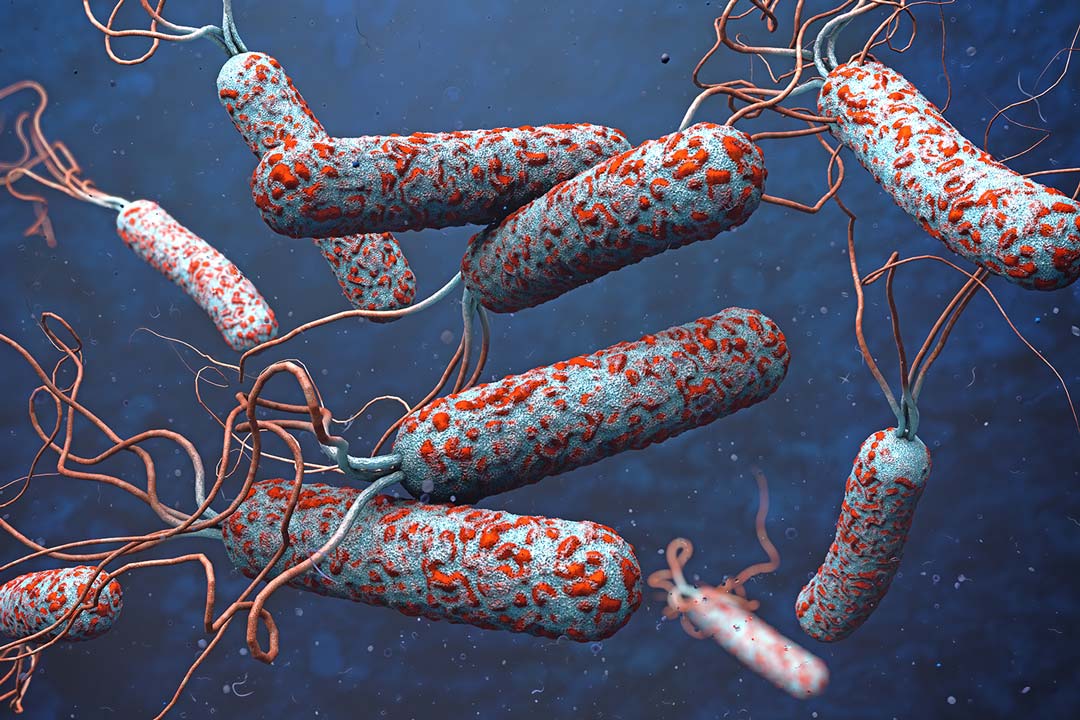

Although Vibrio cholerae, the bacterium that causes this acute gastrointestinal disease that causes acute, watery diarrhoea and vomiting wouldn’t be discovered until 1854 in Florence, at the same time New York was going through a crisis of an epidemic. The disease had originated from South Asia and started spreading in the early 19th century through sailors going from port to port.

But even though they didn’t know what caused cholera, people knew it was more likely to happen in unsanitary conditions with unsafe water, often in crowded impoverished parts of the community. Just as with COVID-19, the wealthy were able to escape the pandemic and leave for the countryside and avoid being infected.

The same year that the bacterium was discovered in Florence, a cholera outbreak in Soho, London, was investigated by English physician John Snow, who studied the routes of transmission, and developed changes in water and waste systems that revolutionised the management of infectious diseases.

Threat to lives

Despite the understanding of the disease and how it spreads, cholera has killed millions through these numerous pandemics – it can be fatal in as many as one in two people infected – and today kills up to 143,000 people a year.

The reason the disease persists, despite a vaccine, is that it thrives in areas of poor sanitation and hygiene, and outbreaks are in areas with poor access to safe water and sanitation such as refugee and internally displaced person camps. In 2010, Haiti experienced one major cholera outbreak, with more than 600,000 cases and 8,000 deaths officially reported, which likely represented only a fraction of the real disease burden that the epidemic caused.

Have you read?

Vaccine development

The first cholera vaccine was developed by Louis Pasteur through testing on chickens in 1877, and in 1884, Spanish physician Jaume Ferran i Clua developed a live vaccine isolated from cholera patients in Marseilles; Ferran then used this on more than 30,000 individuals in Valencia during that year's epidemic.

Sawtschenko and Sabolotny developed the first oral cholera vaccine in 1893. In the 1920s–1930s, field trials were conducted in India on the use of bilivaccine, a commercially prepared tablet containing 70 billion dried V. cholerae organisms. However, it was considered that parenteral vaccines were superior and more practical than oral vaccines until the 1980s, when an increased understanding of intestinal immunity and cholera encouraged a shift from parenteral vaccine to oral vaccine development.

Oral vaccines were first prequalified by WHO in the 1990s, and there are now three WHO prequalified oral cholera vaccines (OCV) that require two doses for full protection. The effectiveness of the vaccine is higher in the first months following immunisation, including when only a single dose is administered. Studies conducted in highly endemic areas like India, Bangladesh or Haiti have proven protection of around 60% in adults lasting up to five years.

Gavi started funding the global cholera vaccine stockpile in 2014. Since the stockpile was launched, millions of doses have helped fight outbreaks and reduce endemic transmission worldwide. Between 1997 and 2012, just 1.5 million doses of oral cholera vaccine were used worldwide. Due to the stockpile, in 2021 alone 29 million doses were given across the globe for emergency and preventive use.

Cholera experts have long been calling for more research to find a more effective and longer-lasting vaccine, with promising conjugate vaccines going under clinical evaluation. Other approaches to develop a better generation of cholera vaccines continue to be explored and early in 2022 researchers developed a new type of vaccine consisting of polysaccharides displayed on virus-like particles. This, they said, could trigger longer-lasting immunity, although the vaccine has not been tested in people yet.

Continued threat

Mass vaccination campaigns can be very effective in outbreaks such as those that occur in humanitarian settings. South Sudan was declared cholera-free in December 2021 after years of continuous transmission. A long-term sustained effort, including the rolling out of reactive and preventive vaccination campaigns to achieve cholera control, helped to turn the tide against the disease.

But, with diseases like cholera, hard won gains can be easily lost.

The Global Task Force on Cholera Control (GTFCC), a partnership of more than 30 organisations including the World Health Organization, has a 2030 roadmap to end disruptive outbreaks and reduce cholera deaths.

As with any infectious disease, prevention, early detection and response is the best way to reduce the public health threat that outbreaks represent. For this, the GTFCC calls for community engagement, improved early warning surveillance, more laboratory capacity and stronger health systems.

In prevention, they advocate for wider access to cholera vaccines, but this needs to go hand in hand with WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) measures and health-system strengthening, as multisectoral approaches are needed to achieve control in areas known to be cholera hotspots.