In rural Isiolo, northern Kenya, the local health clinic has two feet and a kind smile

His name is Samuel Emanman Ekiru, Community Health Promoter, and his superpower is showing up.

- 26 January 2026

- 7 min read

- by Victor Moturi

At a glance

- Kenyan health worker Samuel Ekiru has come up with an innovative solution to access challenges in his region: a one-day pop-up clinic travelling from village to village.

- This predictable care has earned praise from residents, reducing disease and preventable deaths in Isiola county.

- “I was motivated to do this work because our people were losing their lives at a high rate,” said Ekiru.

Fourteen kilometres of rough terrain separate the cluster of manyattas known as Kambi Turkana, in northern Kenya’s Isiolo, from the nearest main road and the closest health clinic.

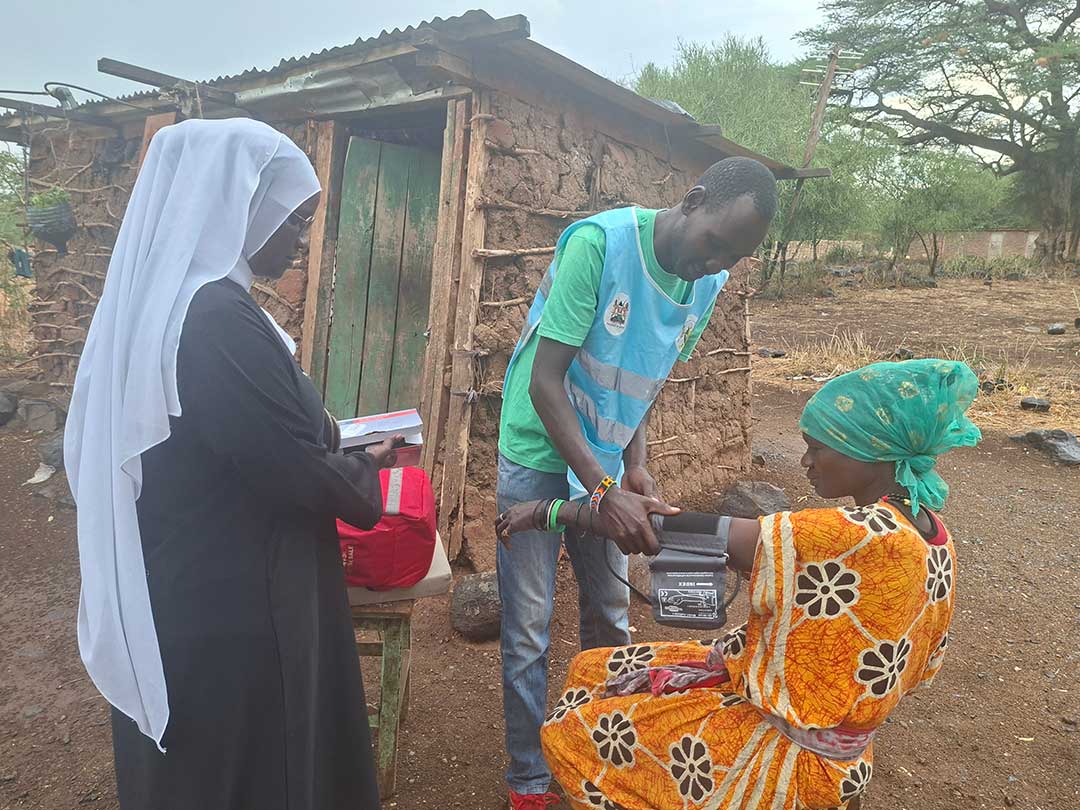

At 09:00 on a November Wednesday, Samuel Emanman Ekiru, a community health promoter (CHP), pushed through strong winds to cross that rocky ground. He carried an extensive medical kit containing everything he hoped he’d need that day to look after the village’s approximately 500 residents: essential drugs and vaccines in a cold-storage container, a blood pressure machine, pain relievers. In case his kit fell short, he also carried a sheaf of stamped referral notes, to dispatch patients to the nearest health facility.

Kambi Turkana residents had already gathered up, waiting eagerly for their turn at ‘Huduma Afya’. The phrase translates to ‘health services’, but here has come to signify Ekiru’s one-day pop-up outpatient clinic.

This model of service delivery is Ekiru’s brainchild, prompted by frustration. In the past, Ekiru had been tasked with a steady target: visit 100 households each month in door-to-door outreaches. But the households were scattered across great distances, and even when he met the target, he worried he was leaving people without the care they needed.

He therefore reorganised his approach: mobile clinics would now be held on scheduled days in different villages, making predictable care available to more people.

Doing more with less

“I was motivated to do this work because our people were losing their lives at a high rate,” Ekiru says. “I used to visit about ten households a day, but since this is not a full-time job, I only managed it at least three times a week,” Ekiru says.

“Because the pay from the county government is low, around 4,000 Kenyan shillings [about US$ 31] and sometimes delayed, I have to do other work to support my family. I realised that many households were being left out, so I started organising village gatherings to reach more people at once,” Ekiru, who also works closely with the Kenya Red Cross, told VaccinesWork.

“Most illnesses I encounter are preventable or treatable flu, diarrhoea, malaria and complications linked to poor sanitation.”

For the ten years he has worked in the community, Ekiru has earned deep trust within the community. “They call me ‘doctor’,” he says with a smile. “They know I am always with them, and that I help whenever there is a problem.”

“Today, many know the importance of vaccines”

The mobile clinics were first rolled out during the COVID-19 crisis, with wider implementation taking shape in 2024. Since then, the initiative has helped to provide essential healthcare services to multiple remote, under-served communities looked after by Ekiru and other community health promoters.

Before the introduction of mobile clinics in this area of Isiolo, preventable deaths were more common, according to Ekiru. Many residents, especially the elderly and women, were forced to walk long distances to reach the nearest health facilities. These journeys often led to delays in treatment, and – in some cases – loss of life.

“Children suffering from diarrhoea and [the consequences of] vaccine hesitancy were very common. Many children were often given traditional concoctions instead of medical treatment, leading to many deaths,” he adds.

“People used to die in large numbers,” Ekiru recalls. “But now, through mobile clinics, people are educated through the CHPs and informed.”

Vaccination is one of the clinics’ biggest success stories, according to Ekiru. “In the past, many parents took their children for the first vaccine only, never returning for follow-up doses. Today, that trend has changed and many now know the importance of vaccines,”

Fourteen kilometres – the distance to the nearest government health facility – is a very long way to most families who rely on walking. It’s especially tough on parents of newborns – during the first three to four months of life the child is expected at several vaccination appointments in close succession.

“The clinic holds child immunisation daily, but the distance becomes a burden,” Ekiru explains. “When our mobile clinic visits the villages, we provide the same vaccinations and child health services closer to home, so families don’t have to make that difficult trip.”

Have you read?

Improved health

“Our health has improved a lot,” says Rosemary Epurkel, a resident of Kambi Turkana. “Huduma Afya teams visit us regularly. They have taught us how to keep our children clean, how to change their diapers properly and how to care for sick children.”

Credit: Victor Moturi

She adds that health workers conduct regular check-ups – even at night when they are called upon. “If they find something [seriously] wrong, they write a referral to the nearest hospital, and immediately we arrive at the hospital, we get help very fast.”

Mikelina Ngimat, another villager, says access to healthcare at night, which the CHPs have made available despite insecurity in the region, has been especially critical. In emergency cases like when a child develops a high fever, residents call Ekiru, who provides first aid before linking the family up to the hospital.

“At night it is risky. There are no vehicles, but [the CHPs] trek long distances to reach us and offer their services when called upon,” says Ngimat.

Joseph Ewoi, a father of three born and raised in Kambi Turkana, says that having healthcare on hand has been a literal life-saver. “I remember one time my neighbour’s wife lost her newborn child while trying to access a health facility,” he recalls.¨

Credit: Victor Moturi

“Mobile clinics have brought services closer to us that once felt impossible to reach. When they come, they treat children, give deworming medicine, check blood pressure and bring vaccines closer to us. Many people now know the benefits of vaccines.”

Funding gaps and government efforts

Despite the progress so far recorded in the community, challenges remain, especially around funding. “There is a problem with setting aside enough money at the county level to tackle more cases,” Ekiru says. “With more funds, we could reach more people.”

According to Corazon Otieno, a nurse and a trained CHP, the Kenyan government has intensified efforts to expand community-based healthcare initiatives in the parts of the country where tough terrain and a low density of healthcare infrastructure make access to essential services especially difficult.

“Across the arid and semi-arid counties, the government is scaling up community clinics and strengthening the network of CHPs to ensure healthcare reaches families directly at the household level,” said Otieno.

Those new and upgraded clinics should bring more services closer to residents, who previously had to navigate great distances for immunisation, antenatal check-ups, malaria testing and chronic disease management.

Improved digital efficiency should also help the CHPs to do more with less. “To improve accuracy and speed of reporting in remote areas, CHPs have been equipped with electronic Community Health Information System (eCHIS) tablets, allowing real-time data sharing with health facilities and county departments,” said Otieno.

Beyond providing clinical care, CHPs are playing a critical role in addressing broader health challenges including nutrition, water safety, maternal health and hygiene, issues that are urgent in drought-prone areas. Their close relationship with households has boosted trust and helped to integrate modern medical services with community traditions.

“These efforts are already showing results, including improved vaccination rates, early referral of pregnancy complications, better disease surveillance and increased uptake of family health services,” reiterates Otieno.

As the programme continues to expand, the government hopes the strengthened community health system will reduce preventable deaths, improve resilience in drought-affected communities, and ensure that even the most marginalised families have access to timely, life-saving care.