Unique and universal: how fingerprint tech is helping get kids protected in Bangladesh

Kids as young as nine months of age can now be biometrically identified ahead of vaccination – creating reliable, verifiable records, and expanding the reach of immunisation.

- 5 October 2023

- 7 min read

- by Mohammad Al Amin , Maya Prabhu

Shartho Barman, aged 15 months and cradled in his mother Dolly's lap, looked apprehensively at the small device the nurse extended towards him. To adult eyes, it looked quite unremarkable: palm-sized, rounded and mute, resembling a wireless computer mouse.

“Privacy-by-design is essential. If it’s not front and foremost, we put it front and foremost.”

Bill Hoggarth, Strategic Partnerships Lead at Simprints

Though it preceded the vaccine needle, all this device wanted from Shartho was a picture – albeit an important picture: one with the potential to reform health system record-keeping, and ultimately help to reliably extend the protection of immunisation to every child.

Credit: Ashraful Arefin

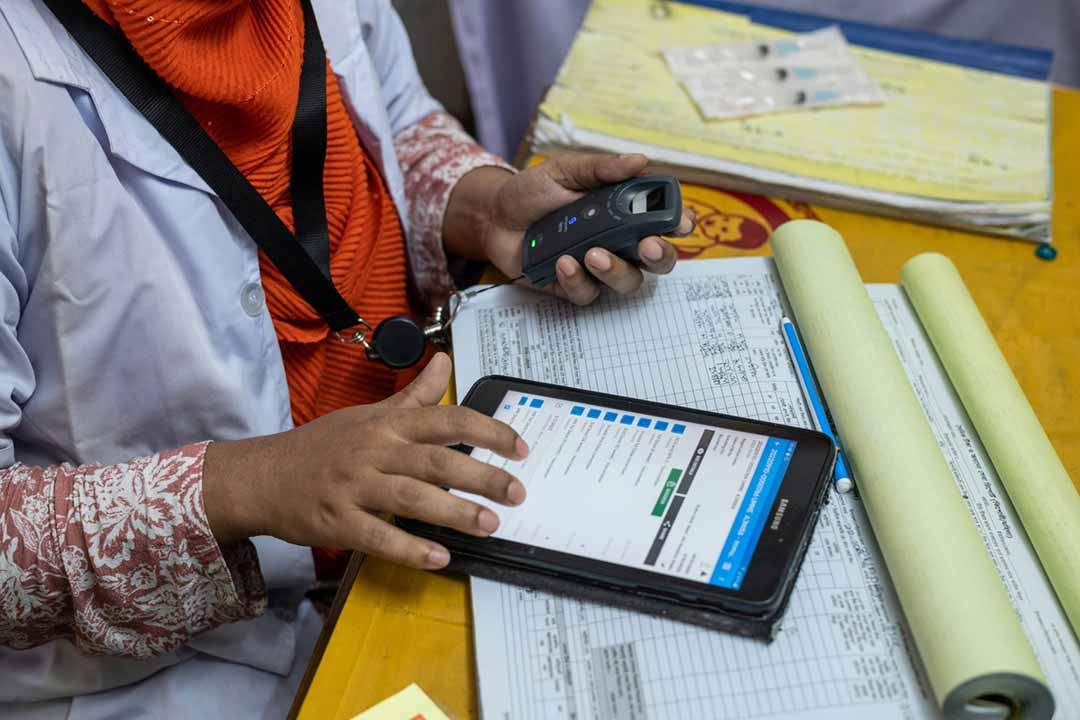

The nurse recruited the thumb from one small hand and pressed its pad to a transparent window of the machine. Called a Vero scanner, the device is the invention of a non-profit company called Simprints, founded to provide ethical and inclusive patient ID powered by biometrics. A light flashed, the image captured. Inside the scanner, a computer parsed the thumbprint image for unique markers – junctions where whorl-lines crossed or met, for instance – and converted those biometric landmarks into a code called a "template".

This template, more unique to Shartho Barman than his name or address or date of birth, beamed its way to the nurse's smartphone over Bluetooth. An app ran a comparison to an encrypted library of thumbprint templates, searching for its match.

It found it. "My baby was registered by this clinic vaccinator when I came here for immunisation with MR1 vaccine," Dolly explained. "The vaccinator took his fingerprint for biometric registration."

This child, the match confirmed, was due for dose two. The nurse injected him with vaccine, and the system recorded it. This child – with this thumb-print – was now covered against measles for life.

A new chapter for an old technology

Initially, Dolly concedes, she was confused – she'd never been asked for her infant's fingerprints before. In fact, not many people have been.

Because fingerprinting is a time-tested technology – there is evidence that handprints were used as identifiers as long ago as the 200s BC in in Qin China – it's easy to miss how novel the process carried out at the Dhaka clinic that mid-August morning was. Until recently, it was considered impossible to get a good fingerprint from a child under five. Not only are children's fingers tiny, but their skin is soft, pliable, and the ridges on their fingers are liable to move and distort in contact with imaging technology.

With support from partners including Gavi and the Bangladesh Ministry of Health, Simprints and NEC, the Japanese global information technology and electronics giant, have worked for years to develop technology sensitive enough to be reliable even in babies as young as nine months, and robust and simple enough to function well in infrastructure-strapped settings.

The reason for their efforts is simple: globally, one in four children go unregistered at birth. This lack of legal registration often leaves health workers struggling to link children to medical records. Demographic identifiers like names or dates of birth frequently overlap. These problems are particularly acute with immunisation, which demands that the system be able to reach the same child six or seven times over the course of 18 months. As a consequence, data errors lead to kids being missed out and mistaken. Conversely, reliable record-keeping can supercharge the capacity of a health system to protect its population.

Have you read?

Bangladesh's pilot programme is at the vanguard of Simprints' global technological roll-out. At 50 clinics in Dhaka and Moulvibazar, 5,499 children have been enrolled while receiving their first measles vaccines, and 2,536 children, including Shantho Barman, have been verified against their stored templates to confirm receipt of their subsequent jab.

Complex, but uncomplicated

At the point of enrolment, Dolly Barman, whose husband keeps a shop in the area, remembers quizzing the nurse – what was the fingerprint for? What would it achieve? "Later, after knowing about it, I was convinced," she recalled.

At a different branch of the Surjer Hashi Clinic network – this one in BCC Road in Dhaka's Wari area – a vaccinator called Anjuman Ara said it's a minority of guardians that share Dolly's initial mistrust. "Sometimes, guardians question about the biometric system – whether there is any harmful effect of taking the fingerprint of a baby with the device. We counsel them about the benefits," she said. "About 80% of guardians appreciate the system in the beginning, while only around 20% ask questions about it," she said.

The questions are understandable: biometric data is sensitive. "Privacy-by-design is essential," said Bill Hoggarth, Strategic Partnerships Lead at Simprints. "If it's not front and foremost, we put it front and foremost."

He means that Simprints takes data security painfully seriously. "We follow the highest encryption standards throughout our application," explains his colleague, Sarah Grieves. "We minimise other data about the beneficiary in a practice known as data siloing. Our partner applications only receive a randomly generated ID that they store with the patient/beneficiary form."

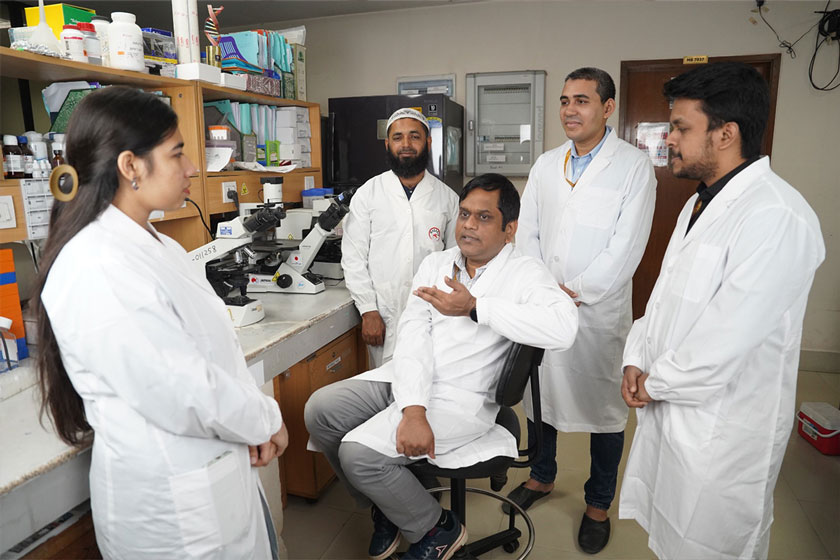

The biometric verification system is a next, not a first, step for Bangladesh's well-established project to digitise immunisation. In fact, Dr SM Abdullah Al Murad, programme manager of the Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI), says the EPI is "one of the most enriched areas of the government health system in terms of digital innovations".

"Over the course of time, resonating with the government'' commitment we have developed an online microplanning tool, EPI vaccination centre app, GIS-based microplanning and individual tracking, rapid convenience monitoring tool, immediately notifiable disease app, AEFI reporting app, real-time EPI monitoring, etc.," he expands.

Credit: Ashraful Arefin

The Simprints trial is at the forward edge of an ambitiously progressive system, in other words. And as complex as the back-end data protection systems are, in practice, the tools are remarkably simple to operate.

Atika Begum, who has worked at the Surjer Hashi Clinic since 2012, says, "Taking fingerprints of the babies is a very easy task with a small electronic device."

She explained the process: "At first I take the fingerprints of the left hand and then of the right hand of nine-month babies for completing biometric registration. Some babies move aside their finger from the device – but I manage it softly."

If the inconvenience to the vaccinator is negligible, the advantages are patent. Says Begum, "If the guardians of babies even lose their paper cards or mobile numbers, we can easily identify the baby with fingerprint checking."

Mohammad Abdul Kader Buiyan, the clinic's senior manager, echoed her. "With the help of the fingerprint saved in the e-tracking system, it is very easy to track the minor babies and identify the vaccine recipients. That helps in preventing drop-out of children from immunisation."

Eager uptake

The novelty of the Simprints/NEC scanning process – which was introduced at the Distillery Road clinic in December 2022 – turns out to offer its own attraction: "The number of children coming to my clinic has increased a little bit after introducing this biometric system with fingerprints for babies, as many guardians are enthusiastic for the system," Buiyan says.

Credit: Ashraful Arefin

One such parent was Asma Akter, whose husband, Sheikh Sadek Wahid, is a cloth trader in the Gendaria area of Dhaka, and whose ten-month old baby girl, Umme Ajmira, had been added to the secure biometric register a month earlier. "I'm very much happy that my little girl is also under a biometric system registration process," Akter said. "I even conveyed the message to my relatives and well-wishers and neighbours who also come to this clinic to immunise their children under the biometric registration system."

Samia, mother of a 16-month-old girl called Zayma, who was too old to be enrolled in the pilot when it began, said "I think it is an exciting matter that my baby could be registered in the biometric system – but I missed it."

A full-scale roll-out is conditional on an evaluation of its performance, according to Dr Al Murad.

Samia is impatient: "The government should introduce this system for all children across the country, for all vaccination and health services, as children get immunisation and health services hassle-free," she said.

Credit: Ashraful Arefin

Barriers to hurdle

When it comes to health systems, hassle-free can mean life-saving. Mohammad Mowla Baksh Chaudhury, a former programme manager of the EPI, described the Simprints system as, "a good thing".

"If it's successfully implemented from the first dose of immunisation of EPI vaccines, then it could be beneficial to reduce drop-out of children from immunisations," he went on. While an impressive 98% of Bangladeshi children receive the third dose of the basic diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis-containing vaccine, and about 93% of children access the second and final dose of measles vaccine, there are still an estimated 30,000 children under age one countrywide who have never received a single jab.

The children of some communities face higher barriers to protection than others. Children who live on the streets, for instance, or the children of brothel workers, often lack the identity documents that can make public services so much easier to access. Making health records accessible by a physical identifier could help unlock vaccination for the most marginalised.

That, in turn, promises not just a change in health outcomes, but the democratisation of public care.

More from Mohammad Al Amin

Recommended for you