We studied drug-resistant bacteria on hospital surfaces in six countries. This is what we found

In 2022 2.4 million new-born babies died of sepsis worldwide. Antimicrobial resistance could pose a further risk.

- 27 November 2024

- 4 min read

- by The Conversation

Antimicrobial resistance happens when bacteria and other microbes that can cause infections gain the ability to resist treatment by antibiotics or other antimicrobial medicines.

Pneumonia, urinary tract infections and sepsis are some of the infections that are usually treated with antibiotics.

Newborn babies are particularly at risk from infections by antimicrobial resistant bacteria. This is because of their immature immune systems.

The risk to babies is greatest in low- and middle-income countries, where infections among newborns are 3 to 20 times higher than in developed countries.

In 2020, 2.4 million newborn babies died of sepsis in the first month of their lives.

Most of these deaths happened in sub-Saharan Africa.

Sepsis is an immune system overreaction to an infection somewhere in the body.

Researchers at the Ineos Oxford Institute for Antimicrobial Research carried out a study to investigate antimicrobial resistance-carrying bacteria recovered from surfaces in 10 hospitals from six low- and middle-income countries.

The hospitals were in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Rwanda and South Africa.

In total, 6,290 hospital surface swabs were processed from intensive care units for newborns and maternity wards.

The swabs were taken from:

- surfaces near the sink drain (including sink basin, faucet, faucet handles, and surrounding countertop)

- emergency neonatal care

- ward furniture and surfaces

- mobile medical equipment

- medical equipment.

Many of the surfaces were found to be colonised with bacteria carrying antibiotic resistance genes. The largest growth was detected near sink drains.

These genes can confer resistance to carbapenem antibiotics, which are last-resort therapies for treating newborn sepsis.

These findings are alarming. They indicate that newborn babies could be at risk of infection by bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics. This could lead to newborn sepsis.

Bacteria colonisation

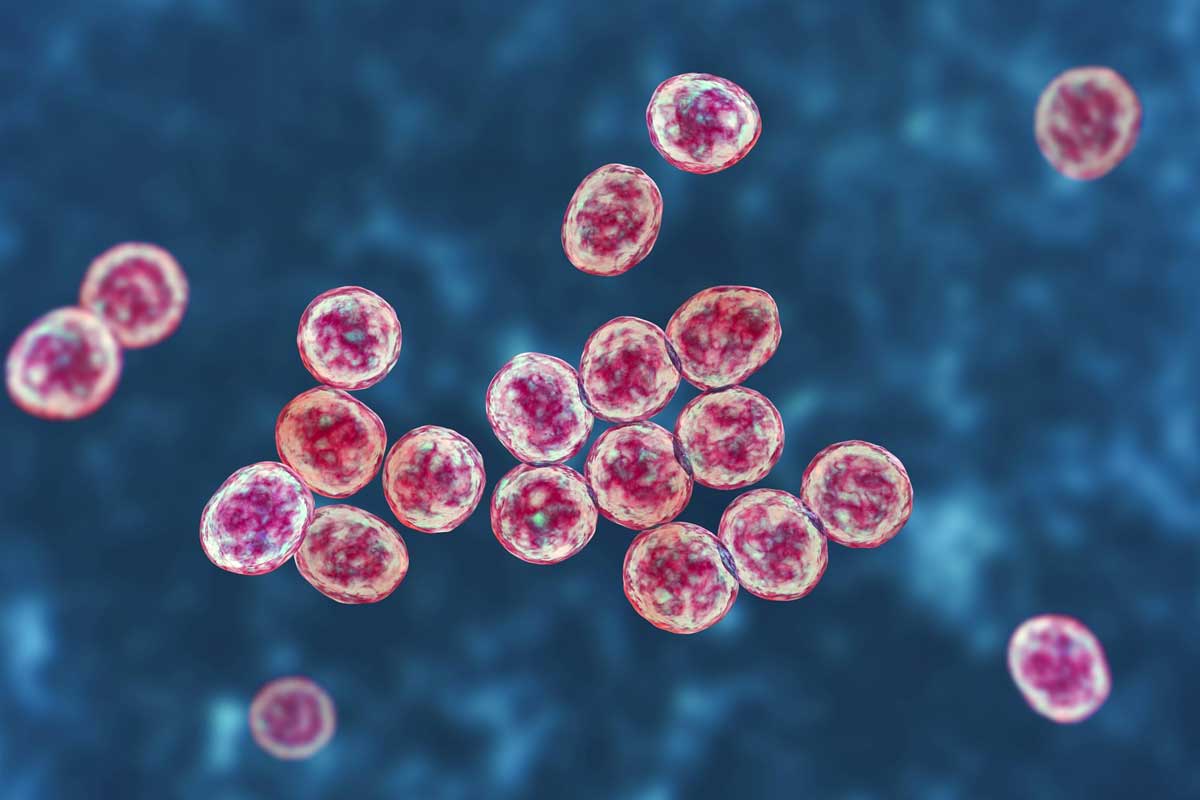

In the study, whole genome sequencing was used to identify bacterial species carrying resistance to carbapenems.

Carbapenems are a last resort antibiotic used when other medicines no longer work to treat an infection.

In the study, 18 different bacterial species carrying carbapenem antibiotic resistance genes were recovered from hospital surfaces.

These included bacteria that can cause pneumonia, urinary tract infections and blood infections.

In one of the hospitals, a bacterial clone which was present on hospital surfaces was at the same time found causing sepsis among newborn babies.

This could mean that bacteria from the hospital surfaces could potentially be transmitted to newborn babies. Future research will need to confirm this.

Antibiotic resistance genes are often found on mobile parts of DNA that can be passed from one bacterium to another. This is through a process called horizontal gene transfer.

These mobile elements move between nearby bacteria, helping resistance genes to spread. This means that antibiotic resistance can quickly pass to different bacteria on the same hospital surface or across various surfaces. It makes infections harder to treat and increases risks for patients.

The study findings highlighted the possible antimicrobial resistance spread between different types of bacteria on the same hospital surface or across different surfaces. This was due to the presence of similar mobile genetic elements in different bacterial species.

This puts patients at greater risk of acquiring an infection. And their treatment options could be limited because the bacteria infecting them are resistant to antibiotics.

Have you read?

Looking ahead

Antibiotic resistance is a substantial economic burden to the whole world.

In 2006, in the US alone, deaths associated with pneumonia and sepsis, mostly, cost the US economy US$8 billion.

Our work points to the need for an urgent review of infection prevention and control guidelines, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

A number of steps could reduce the risk of hospital-acquired infections. For example, ensuring:

- safe drinking water

- vaccinations to reduce infection and the need for antibiotics

- hospital infrastructure for waste management and recycling

- tailored infection prevention and control programmes in health facilities, including cleaning and disinfecting hospital surfaces.

A major challenge is that hospitals in low-resourced countries may not have funds and resources needed to implement or maintain these measures.

Financial institutions and governments therefore ought to invest in these preventive programmes.

Accessible, effective and sustainable infection prevention and control measures could prevent the deaths of thousands of newborn deaths.![]()

More from The Conversation

Recommended for you