What are monoclonal antibodies – and can they treat Covid-19?

For more than 30 years, monoclonal antibodies have transformed the way we treat many diseases. Researchers think they are also one of the most promising treatments for Covid-19. Here's why.

- 7 October 2020

- 9 min read

- by Wellcome

1. What are monoclonal antibodies?

Monoclonal antibodies are a class of medicines that have transformed the way we prevent and treat diseases, from cancer and diseases of the immune system, to childhood viral infections.

They are not chemical compounds, as most drugs are. They are based on natural antibodies – which are proteins that the body produces to defend itself against disease – but are created in the lab and mass-produced in factories. This is why they’re sometimes called ‘designer antibodies’ – they are tailor-made to the disease they treat.

The first monoclonal antibody product was licensed more than 30 years ago. Since then, millions of people have benefitted from more than 100 such treatments. Around 50 of these were brought to market in the past six years alone.

This is one of the fastest-growing fields in biomedical research, and an increasingly important segment of the pharmaceutical market – last year, seven of the top 10 best-selling drugs were monoclonal antibodies.

2. How do they work?

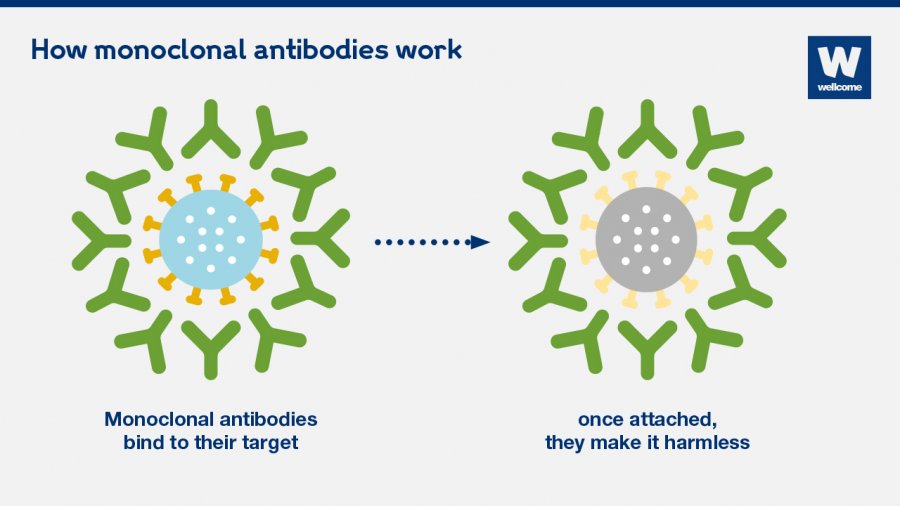

Antibodies are proteins produced by our immune system and are one of the main ways the body defends itself against diseases.

They work by binding to their specific targets – for example viruses, bacteria or cancerous cells – and making them harmless. They block the action of the target, or they flag it as foreign so that other parts of our immune system can clear the ‘invaders’ away.

Monoclonal antibodies work in the same way too.

They bind to their specific target, without harming anything else in their way. This target is not always a ‘foreign intruder’, like a virus. Antibodies can be designed to attach to different molecules in the body, for example, to turn down the immune response when it overreacts; this phenomenon, which also happens with some Covid-19 patients, is called a ‘cytokine storm’.

Due to their numerous applications, monoclonal antibodies have been safely and effectively used to treat a growing number of diseases, some of which were difficult to treat in the past.

3. How are they made?

Making monoclonal antibodies is complex and expensive.

First, scientists extract the relevant antibodies from human blood. Then they replicate and manufacture them in large quantities.

Most monoclonal antibodies are produced in Chinese hamster ovary cells which are typically grown in large bioreactors for around 10 to 15 days. The resulting antibodies are then purified and packaged so they can be easily administered.

This whole process takes a long time and uses costly materials. Some estimate that the cost of producing one gram of marketed monoclonal antibodies is between $95 and $200; this doesn’t include the costs of research and development, or packaging, delivering and administering the medicine. The costs are even higher for start-up companies.

Manufacturers are looking into ways to reduce production costs, for example through novel technologies and using alternatives to hamster cells (such as algae, yeast and plants) that would change the way these drugs are made.

Have you read?

4. What diseases are they used for?

The majority of the monoclonal antibodies on the market are for noncommunicable diseases, such as autoimmune diseases, like rheumatoid arthritis and cancer.

In the past few decades, cancer immunotherapies have saved the lives of millions of people around the world. Monoclonal antibodies have transformed the way we treat multiple cancers, including breast cancer, for which the drug Herceptin has been a game changer.

Out of more than 100 licensed monoclonal antibodies, only seven are for treating and preventing infectious diseases – though many more are in development, including candidates for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19.

Monoclonal antibodies could have a huge impact on the way we treat and prevent infectious diseases. And there are already promising signs.

Two experimental antibody therapies against Ebola are being used to great effect as part of an emergency access programme in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

And several antibodies that can act against different strains of HIV are also in development.

5. Can monoclonal antibodies treat Covid-19?

For the past 30 years, monoclonal antibodies have transformed the way we treat various diseases – they proved to be more effective, better tolerated and easier to deliver than other treatments.

Researchers are optimistic that monoclonal antibodies could help prevent and treat early infections of Covid-19 too.

Some of the advantages they offer are:

- they can specifically target the SARS-CoV-2 virus because they originate in the blood of people who have recovered from Covid-19; this would potentially make them more effective than other drugs.

- they can be rapidly isolated and manufactured – since the pandemic started, more than 70 monoclonal antibody products for Covid-19 are now in development.

- they can provide rapid protection against infection – once administered, monoclonal antibodies enter the bloodstream straight away and offer immediate protection for a few weeks or months. Vaccines take a few weeks to have an effect, but usually provide long-term protection. This is why researchers are optimistic that monoclonal antibodies could complement vaccines in helping to contain the pandemic.

- they have the potential to treat infected patients or prevent infection in all individuals, including the elderly and young children, and immunocompromised people – some of whom can’t receive a vaccine, or for whom vaccines don’t always work as well.

6. How many monoclonal antibodies for Covid-19 are in development?

Since the start of the pandemic researchers have been rapidly evaluating existing drugs and developing new treatments – including monoclonal antibodies – to treat Covid-19 patients.

Several monoclonal antibodies that are licensed or in development for other diseases are in clinical trials to see if they have an effect on Covid-19 patients. One of these is adalimumab, used to treat arthritis and Crohn's disease; the University of Oxford recently launched a trial to look at its potential to treat people in care homes, funded by the COVID-19 Therapeutics Accelerator.

Researchers have also been rapidly identifying monoclonal antibodies that specifically target SARS-CoV-2. More than 70 such products are already in development.

The pharmaceutical company Lilly, in collaboration with AbCellera, launched the first human study of a potential Covid-19 antibody treatment in May-June this year. Other safety clinical trials followed, including studies by AstraZeneca, Celltrion and Regeneron.

7. When will Covid-19 monoclonal antibodies be available, and who will get them?

The speed of research into Covid-19 treatments has been unprecedented.

One of the advantages of monoclonal antibodies is that clinical trials can happen even more rapidly; because these are based on natural antibodies, not chemical compounds, safety trials take less time.

In less than four months since the start of their clinical trials for Covid-19 antibody-products, Lilly and Regeneron published early results showing encouraging signs. Results from other clinical studies are expected later this autumn.

Knowing if any of these antibody treatments are safe and effective for treating or preventing Covid-19 is only the first step.

Making them available to patients will depend on many other things, such as manufacturing capacity – how quickly large quantities of the effective treatment can be made. It will also depend on price – who will be able to afford to buy them.

The ACT-Accelerator is a ground breaking collaboration created for exactly this purpose – to make sure that any Covid-19 treatments, vaccines and tests will be accessible to those who need them most, across the world, not only in the countries that can afford to pay the highest costs.

8. Are monoclonal antibodies expensive?

Monoclonal antibodies are more complex and expensive to produce than other types of drugs. This makes them some of the most expensive drugs in the world, unaffordable for most of the world’s population.

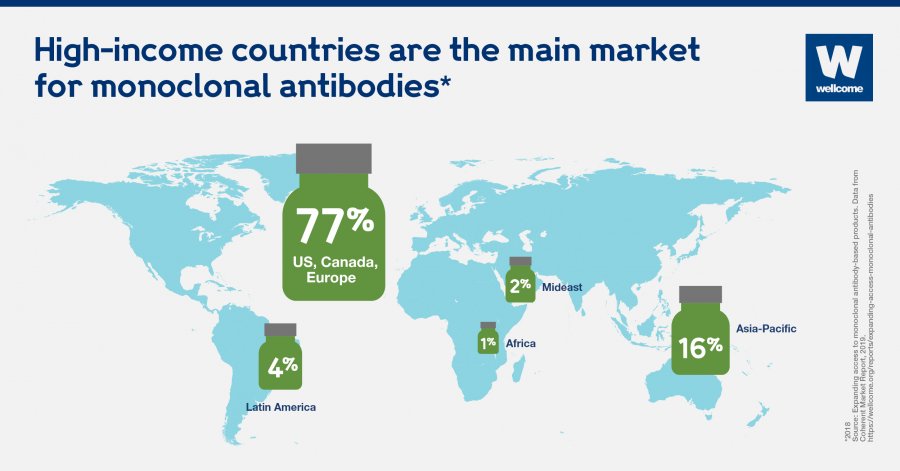

The median price for monoclonal antibody treatments in the US ranges from $15,000 to $200,000 a year. Although drug prices vary greatly worldwide, companies that market many of these treatments focus primarily on high-income countries, where prices are the highest.

As a result, almost 80 per cent of monoclonal antibodies are sold in the US, Canada and Europe. That could change.

Biosimilar products are one way to reduce production costs and make these innovative treatments cheaper. Once the original monoclonal antibody product is off patent, companies can create similar, but cheaper products. An example is Canmab – a biosimilar version of the breast cancer drug Herceptin – which sells for $100–$200 per dose in India. This is significantly less than the $1,800 price per dose in the US.

Another way companies can make monoclonal antibodies cheaper is by introducing second brands which can only be sold in low- and middle-income countries. One example is Herclon, another brand that Herceptin is sold as.

9. Are they available everywhere?

Antibody treatments are not widely available, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Although 85 per cent of the global population live in these countries, they account for less than 20 per cent of the global sales of monoclonal antibodies.

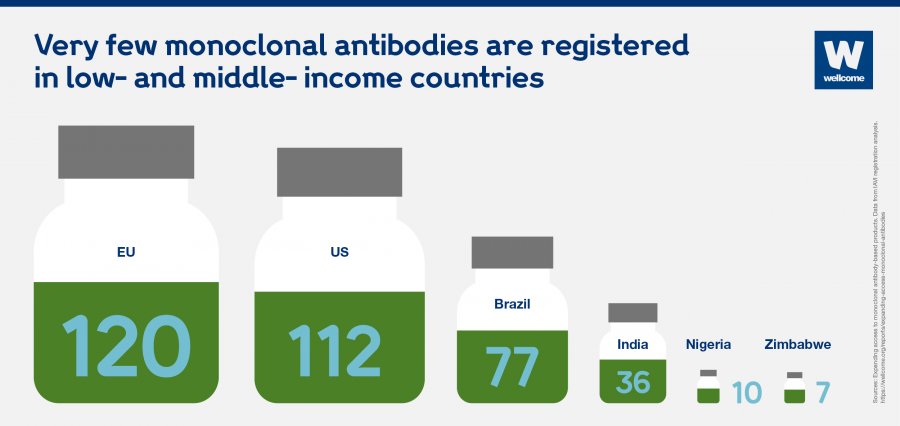

Very few licensed monoclonal antibodies are even registered in low- and middle-income countries.

That’s true even for some infectious diseases that affect developing countries more than the rest of the world. For example, 99 per cent of deaths caused by respiratory syncytial virus are in low- and middle-income countries. But 99 per cent of the sales of Synagis, an antibody-based preventive, are in the US and Europe.

And the few monoclonal antibodies that are registered in low- and middle-income countries are often unavailable through the public health system, so unaffordable to most people.

India is one of the few middle-income countries that stands out, mainly because of its local manufacturing capacity – it has more than 100 companies that make biosimilar products. Still, people in India only have access to a fraction of the antibody products from the US market.

10. What will it take to make monoclonal antibodies more available and affordable?

Millions of people around the world could benefit from existing monoclonal antibody treatments and those in development – including the ones for Covid-19, which could help bring the pandemic to an end.

These innovative products are not currently accessible for most of the world’s population. That could change if governments, the bio-pharmaceutical industry, global health organisations and funders work together.

Some of the things they could do to make monoclonal antibodies more available across the world include:

- spreading the word about how valuable antibody therapies can be for treating a range of diseases, and advocate for greater access

- making it easier to register antibody therapies in low- and middle-income countries

- developing guidelines for monoclonal antibodies to make sure that these products are designed with the needs of local populations in mind.

To make monoclonal antibodies more affordable, they should:

- invest in innovative technologies that could lower production costs

- create new business models that enable different market approaches in low-, middle- and high-income countries

- establish collaborations between public, private and philanthropic organisations to focus on the needs of the developing countries.

Original article

This article is republished from Wellcome. Read the article here.