The 1970s whooping cough vaccine scare

In 1974, one small, flawed UK study linked the pertussis vaccine to neurological problems. The result was nationwide panic and epidemics that claimed the lives of over 30 children. The repercussions can still be felt today.

- 27 October 2025

- 17 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

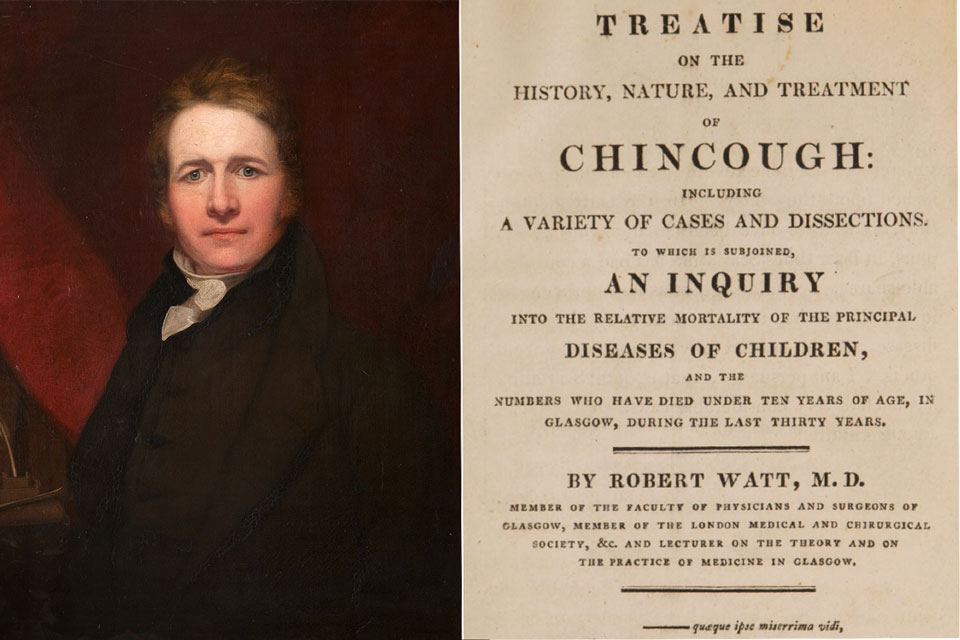

In January 1974, at the dim beginning of a gloomy year for the United Kingdom, a small study was published in a medical journal.

It was a case series of 35 children who had been treated over a period of 11 years at Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital in London [1]. All of the children had presented with severe neurological problems of various descriptions. Four of the children eventually recovered; two died. Most of the children survived with intellectual deficits or epilepsy or both.

What made them a group worthy of collective analysis, to the minds of the report’s authors, was that all the children had shown at least some signs of neurological illness shortly after receiving a dose of the pertussis, or whooping cough, vaccine.

They acknowledged that chance temporal relationships to “such events as teething and inoculation” are liable to crop up in any case of childhood illness – because almost all children, well or unwell, will be vaccinated at several stages in infancy. They also found that 12 of the children had shown signs of vulnerability, like convulsions, before vaccination.

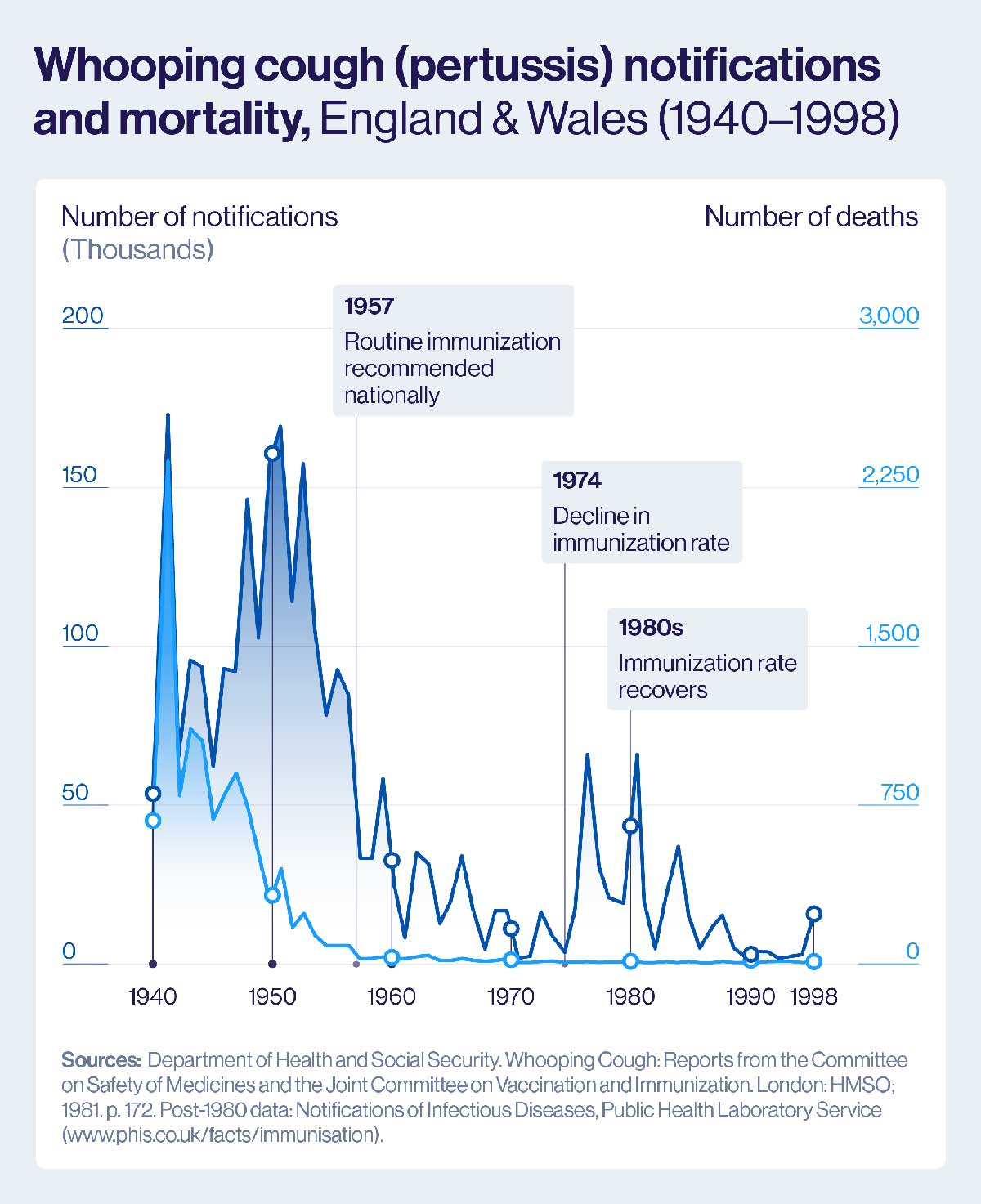

Pertussis immunisation rates in the UK tanked fast: by 1978 just 30% of the country’s children were protected, and in some areas coverage rates had sunk as low as 9%. An epidemic was predicted; three came.

Yet still the researchers concluded that in at least these 35 instances, the link between immunisation and neurological damage was likely to be causal.

In newsprint and on TV broadcasts, the story blew up.

Around 80% of the UK’s kids had received a vaccine that was now being spoken of in connection with brain injury: alarm was widespread. People who believed that their own children’s disabilities might have been triggered by the jab banded together as a campaigning group, as the Association of Parents of Vaccine-Damaged Children, to agitate for compensation [2].

In the public imagination, the threat they spoke for – the alleged risks of immunisation – faced a muted challenger: the jeopardy of the uncontrolled disease was more or less forgotten.

After approximately two decades of routine pertussis vaccination (typically as part of the diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus-containing vaccine, or DPT), whooping cough case rates had plunged in the UK, like in much of the industrialised world. Few people knew the characteristic sound [3] of a child braying for breath [4], and few remembered how often [5] that sound had been a forewarning of loss.

Pertussis immunisation rates in the UK tanked fast: by 1978 just 30% of the country’s children were protected, and in some areas coverage rates had sunk as low as 9%. An epidemic was predicted; three came.

The first and worst landed between 1977 and 1979. By its end, more than 102,500 cases of whooping cough had been reported, and an estimated 36 children – most of them babies – had died.

Was the pertussis vaccine panic warranted?

In a word: no.

The public voices who counselled rattled parents that the vaccine was “worthwhile” – protective, low risk [6] and, decisively, lower-risk than not vaccinating – would be vindicated by the spate of studies released over the subsequent decade and a half.

Still, definitive reassurance took time to crystalise out of the data. In fact, the first impactful, large-scale piece of epidemiological research to come out suggested a modest [7] link between the pertussis vaccine and neurological illness.

Conducted between 1976 and 1979, the National Childhood Encephalopathy Study (NCES) looked at 1,000 children who had been admitted to hospital with central nervous system disease. Only 35 of those 1,000 children had received the pertussis antigen within seven days of symptom onset.

Both the re-investigation of the old NCES data and three recent, large, controlled studies had turned up “no evidence of a causal relationship between pertussis vaccine and permanent neurological illness,” Cherry wrote. “The major problem has been the failure of observers to separate sequences from consequences. The two are not synonymous.”

The researchers matched their hospitalised subjects with control children, crunched the numbers and came up with an estimation of risk: one case of acute encephalopathy could be expected for every 110,000 vaccines, they wrote. Lasting damage could be expected to occur at a rate of one case per 310,000 vaccines.

By these figures, the danger was much smaller than had been alleged by the vaccine’s opponents, and small enough to confirm the Department of Health in its continued recommendation of the pertussis vaccine. But several subsequent, respected studies – including a re-analysis of the original NCES data [8] – would find that even this very slight risk was a problematic overestimation.

By 1990, John D. Cherry, a highly-regarded professor of paediatric infectious disease [9], decided enough evidence had been accrued. He published an editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) in which he called it: ‘pertussis vaccine encephalopathy’ was a myth.

Both the re-investigation of the old NCES data and three recent, large, controlled studies had turned up “no evidence of a causal relationship between pertussis vaccine and permanent neurological illness,” Cherry wrote.

“The major problem has been the failure of observers to separate sequences from consequences. The two are not synonymous.” The years since have borne out his conclusions. [10]

But the horse had bolted long ago. Although pertussis vaccination rates in the UK rebounded to a steady 92% by 1992, hundreds of thousands of children had, by that point, confronted their most vulnerable years under-protected. Many tens of them had died unnecessarily.

As Cherry appreciated with rueful foresight, the terms of public discussion about vaccines, in the UK as in the US, had changed in enduring ways.

A misplaced vote of no confidence?

Vaccines are biological products with biomedical and epidemiological purpose, but decision-making about vaccination is never solely, and often not even principally, a biomedical or epidemiological question.

If they thought they were protecting their children, the parents who opted out of pertussis immunisation in the mid-1970s were wrong. But their worry – like most bouts of public anxiety – was reasonable.

For one thing, the whole-cell pertussis vaccine is, by vaccine standards, a bruiser.

Vaccines differ because the pathogens they mimic or borrow from to produce a protective effect differ. The pertussis bacterium causes illness by releasing a number of different exo- and endotoxins. Still today, the most effective pertussis vaccines we have use both a killed, whole version of both the bacterium itself, and the neutralised toxins, to stimulate an immune response.

That reaction is safe, but often unpleasant. Fevers and localised pain and swelling are common. High fevers occur in a small minority of cases. Fevers high enough to precipitate febrile convulsions are rare but not unheard of.

Asking the parent of, say, an epileptic child to accept that, despite coincident timing, the child’s reaction to the vaccine has nothing to do with the seizure disorder that has since revealed itself, wants trust as much as it wants good evidence.

Although pertussis vaccination rates in the UK rebounded to a steady 92% by 1992, hundreds of thousands of children had, by that point, confronted their most vulnerable years under-protected. Many tens of them had died unnecessarily.

Trust in public authority is a political question. In the UK in 1974, trust, like the national power supply, was short.

The year began in darkness. A global oil crisis and coal miner’s strikes at home led the wrong-footed Conservative government to call for a policy of electricity rationing. A three-day working week was announced in December 1973: starting in the new year, businesses were to shut their doors and turn out the lights out for the week’s remainder.

The high streets were forlorn, the economy was in recession, unemployment rates were high, and IRA bombs were going off on the British mainland with some regularity.

In February, a general election produced a hung parliament. Some political dithering and a tepid, rainy summer followed, and then came 1974’s second general election.

The nation appeared, in short, to be in its dingy ebb-tide. Far away in what had once been Britain’s expansive imperial forecourt, Idi Amin, President of Uganda, appealed to his countrymen for donations in cash and vegetables to “Save Britain,” and “help their former colonial masters”.

Who knows best?

Whether the UK’s public institutions would, in this moment, have been capable of quickly and decisively staunching a haemorrhage of trust in the pertussis vaccine remains to some extent a question of speculation, because they barely tried.

“Though the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunization met and affirmed the vaccine [11], the government (reflecting a general climate of uncertainty) launched no major campaign to restore public confidence,” writes Jeffrey P. Baker in his 2003 essay on the crisis.

Not even the medical profession rallied behind the JCVI’s judgement. Certain doctors had had taken a vocal, activist stance against the pertussis vaccine – physician-epidemiologist Gordon Stewart notably campaigned alongside the Association of Parents of Vaccine-Damaged Children.

But even among the quieter mass of his colleagues, opinion had fractured [12]. A 1977 survey in the Times of London found 47 out of 97 general practitioners would not recommend the pertussis vaccine unless asked for it by the parent.

In the same moment, the traditionally authoritative standing of the family doctor was under new challenge. In the US, where a similar pertussis vaccine controversy picked up momentum into the 1980s, and the UK [13], the feminist movement was finding ways to articulate the systemic marginalisation of women in healthcare [14].

A dominantly male medical establishment had monopolised knowledge that could empower women, and along the way, often let women down, sidelining female experiences, withholding pertinent data and, in at least one burningly memorable scandal, making catastrophic prescriptions.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Thalidomide, then marketed as a morning-sickness pill and given to pregnant women principally in Europe, had caused an estimated 10,000 babies to die, and many thousands more to be born severely disabled.

As the drive for “informed medical consumerism” established itself as a core principle in the American women’s health movement, it also loaned a grammar to another small, increasingly influential group: vaccine-critical parents [15].

“Mothers, who are primarily responsible for taking children to the doctor and holding them while vaccinations are given, must stop being intimidated by physicians,” wrote Barbara Loe Fisher in 1983. “We must educate ourselves about vaccines, start asking questions and demanding answers.” A year earlier, inspired by a sensationalistic television report called DPT: Vaccine Roulette, she had founded a group called Dissatisfied Parents Together – DPT for short.

Like the Association of Parents of Vaccine-Damaged Children in the UK, DPT did not claim point-blank opposition to vaccination, instead agitating for “safer vaccines”, more information for parents, more research on adverse reactions and remuneration for families of injured children.

But they also drew the media spotlight to parent after parent who claimed vaccination was to blame for their child’s infirmity, helping stoke anxiety and drive the conflation of causation and correlation that Cherry would diagnose as the root of a “new national tragedy” in 1990.

By 1984, their campaign was helping choke out the pertussis vaccination programme right at the source.

Market-CPR in the USA

In America, the pertussis vaccine controversy never did produce the same radical cratering of immunisation rates that it had in the UK. It did, however, trigger an avalanche of litigation.

Lawsuits concerning alleged cases of pertussis vaccine injury came for the vaccine’s makers – pharma companies. By 1984, two out of three American manufacturers had dropped production of the DTP vaccine; just one distributor remained. In December that year, the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) warned of looming shortages.

Public spending had underwritten the success of immunisation in the US so far, and it would have to again. In 1986, Ronald Reagan signed into law the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Compensation Act, establishing a no-fault compensation programme for alleged vaccine injuries [16].

As far as its immediate objectives went, the plan worked: pressure on manufacturers lifted, and the supply choke eased. But complications lurked.

The principle wasn’t the problem: the argument for financial compensation for vaccine-induced harm was strong [17]: vaccination serves a shared, public purpose, as well as an individual one, and it makes sense that the costs of an injury sustained in its pursuit should be collectively borne.

In the UK, that moral point had been won by 1977, according to historian Gareth Millward, when the Cabinet, hoping to restore confidence in the immunisation programme, resolved to accept the general proposition of compensation for victims of vaccine damage. The Vaccine Damage Payments Act 1979, as well as the first pay-outs [18] on its basis, followed a couple of years later.

Instead, the difficulty in was in the mechanism of adjudication [19]. In his 1990 editorial, John D. Cherry wrote that the American Vaccine Injury Compensation Program “has legitimized ideas as to causation that were made by the special interest groups and by physicians not trained in epidemiologic science.

“Unscientific precedents have been set for what is and is not a vaccine-related injury.”

In other words, the so-called “vaccine court” was creating a parallel structure of evaluation that had more to do with reputational and ultimately financial expediency than with the actual safety and efficacy profile of a given vaccine.

Indeed, according to the website of the Health Resources and Services Administration, “approximately 60% of all compensation awarded by the VICP comes as a result of a negotiated settlement between the parties in which the HHS has not concluded, based upon review of the evidence, that the alleged vaccine(s) caused the alleged injury.”

Where would it lead? In the case of the American pertussis furore, Cherry foresaw an end to the “national nonsense” only by means of a change of vaccine: “not to prevent non-existent problems such as “pertussis vaccine encephalopathy,” but to decrease the many disquieting reactions.”

The high fevers, crying and fits that “do occur with presently available whole-cell pertussis vaccines,” were not a risk [20] to children’s neurological health. But they evidently had potentially grave ramifications for the health of the immunisation system as a whole.

Is the nicer vaccine the better vaccine?

The acute part of the crisis abated without a vaccine switch-up. American industry had its legal backstop; the UK had pertussis.

In December 1977, as new reported whooping cough cases reached 1,200 per week, British papers reported that a rush on pertussis vaccine had left the country facing a shortage.

The Times quoted a Department of Health official as saying that parents who had rejected the pertussis component of the triple vaccine when their children were younger were “now waking up to the fact that their children are not protected”.

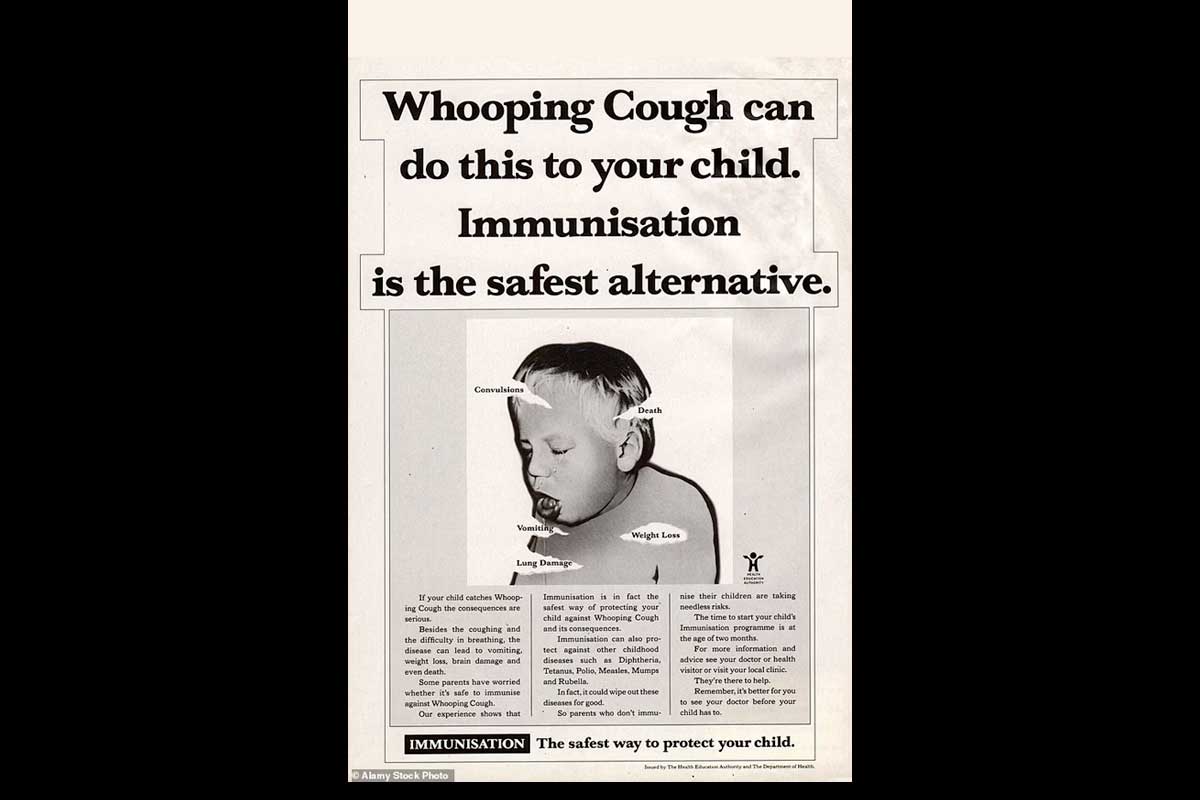

In anticipation of a second epidemic – which arrived in 1982 – the government changed tack, planning a major immunisation campaign and a publicity offensive in its aid.

“Vaccination protects,” splashed one newspaper advert placed by the Department of Health and Social Security over an image of a young mother embracing her child. In 1982, the palace let it be known that baby Prince William had received his DTP shot. Pertussis immunisation rates picked up steadily into the 1990s and, accordingly, whooping cough cases fell.

Still, the whole-cell pertussis vaccine had been left damaged by the crisis. Most high-income countries – beginning with Japan in 1981 [21] – including the US and the UK, did make the transition to a different kind of pertussis vaccine when it became available.

The new vaccines were acellular rather than whole-cell vaccines, meaning they included a couple of selected antigens instead of the whole, naturally-occurring lot. This birthed the new acronyms DTaP (the newer diphtheria, tetanus and acellular pertussis vaccine) and DTwP (the existing diphtheria, tetanus and whole-cell pertussis vaccine).

The pioneer example of these acellular vaccines, developed by Yuji Sato in the 1970s, included just pertussis toxin (PT) and filamentous haemagglutinin (FHA), leaving out the reactogenic lipopolysaccharides and endotoxins that were present in the whole-cell vaccine.

Trials showed that these vaccines – soon incorporated into the standard three-part jab as DTaP – were, indeed, gentler.

“This could be the end of the story, except that in countries using DTaP there is now a resurgence in cases of whooping cough, with the characteristic peak every 2–5 years that was observed in the pre-vaccine era,” wrote Nicolas Fanget in Nature in 2020.

Since the 1990s, the trade-off has grown clearer: DTaP may be less prone to painful side effects than DTwP, but it’s also somewhat less efficacious. “Since 1997, the DTaP vaccination policy has created a cohort of people (the number of which is expanding yearly) who are more susceptible to repeated clinical illness with B pertussis infection than are DTwP-vaccinated children,” wrote James D. Cherry.

But is the better vaccine the more popular vaccine? Has a compromise on efficacy saved evidence-backed immunisation programmes from unnecessary crises of confidence?

Well, no [22].

[1] Kulenkampff M, Schwartzman JS, Wilson J. Neurological complications of pertussis inoculation Archives of Disease in Childhood 1974;49:46-49.

[2] Read more on their campaign for vaccine injury compensation: Millward G. A Disability Act? The Vaccine Damage Payments Act 1979 and the British Government's Response to the Pertussis Vaccine Scare. Soc Hist Med. 2017 May;30(2):429-447. doi: 10.1093/shm/hkv140. Epub 2016 Aug 4. PMID: 28473731; PMCID: PMC5410922.

[3] “We collected specimens by light of kerosene lamps, from whooping, coughing, strangling children. We saw what the disease could do,” said scientist Grace Eldering, recalling the 1930s research that work produced the world’s first widely-deployed pertussis vaccine

[4] “Whooping cough? Who’s ever heard of whooping cough? […] I just didn’t realize how serious it could be,” Karen Pfeffer, a 22-year-old mother told the Washington Post in 1975, after her child contracted a near-fatal case of the disease. Quoted in Elena Conis, “A Mother’s Responsibility…,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Fall 2013.

[5] In 1900, infant mortality from pertussis in the United States as 4.5 deaths per 1,000, dropping to 0.003 deaths per 1,000 by 1974. Between 1921 and 1930, 44,000 deaths in the England and Wales were attributed to pertussis – an average of 4,400 each year. In the 1940s, still 1,000 deaths a year were attributed to whooping cough. In 1957, the year the vaccine was introduced nationwide, that figure plunged to 100. In 1974, just 13 whooping cough deaths would be recorded.

[6] The landmark Medical Research Council trials of the 1940s supplied a robust evidentiary basis for this claim.

[7] For comparison, the global lifetime risk of being struck by lightning is estimated to be approximately 1 in 3,000.

[8] MacRae KD. “Epidemiology, encephalopathy, and pertussis vaccine”. In: FEMS Symposium pertussis. Proceedings of the Conference Organized by the Society of Microbiology and Epidemiology of the GDR. April 22, 1988

[9] Then in the UCLA medical department, Cherry arguably (co-)wrote the book on childhood infection

[10] Further studies have failed to turn up a causal link between the vaccine and brain injury. A 2004 study from Canada took a closer look at seven cases of encephalopathy that had begun wthin a week of pertussis vaccination and found “a more likely cause…in each instance.” A 2006 retrospective case-control study of more than 2 million children, found that “DTP and MMR vaccines were not associated with an increased risk of encephalopathy after vaccination.” Authors of a 2011 study, which looked at 246 paediatric encephalitis cases from a ten-year period in California, found “no association between receipt of currently-recommended immunizations and subsequent development of encephalitis was observed.”

[11]“In 1974 it was recommended that pertussis vaccine should continue to be offered in a triple vaccine together with diphtheria and tetanus vaccines. Further data on the prevalence of whooping cough and the incidence of adverse reactions have shown no reason to change this policy; the hazard of whooping cough remains greater than that of immunization,” read the JCVI statement published in the British Medical Journal in 1975.

[12] “Sir, it must be very difficult for both doctors and parents to make up their minds about the risks of vaccination against whooping cough when such widely differing figures are being bandied about … as a practising clinician who witnessed the effect of this prolonged and debilitating illness on children and their parents, I welcome the advice of the JCVI […] that the benefit of the vaccination outweighs the risks and would urge, though not order, others to follow this guidance,” wrote consultant paediatrician James Appleyard in a 1981 letter to the editor of the Times.

[13] According to Lesley Doyal, the 1970s in the UK were “a period of growing awareness that certain areas of knowledge that had previously been monopolised by doctors were potentially of immense value to women – knowledge about how our bodies work, for example.” Quoted in Zoe Strimpel’s “Spare Rib, The British Women’s Health Movement and the Empowerment of Misery”

[14] Elena Conis’s 2013 article “A Mother’s Responsibility: Women, Medicine, and the Rise of Contemporary Vaccine Skepticism in the United States” is a highly recommended read.

[15] Conis again

[16]Between 1986 and May 2023, the NVICP awarded a total of US$ 4.6 billion.

[17] The present writer, who believes all illness and disability should be a public responsibility, takes little convincing .

[18] These were of relatively modest scale: £10,000 was awarded to each of 349 children in 1979, and to 255 more in 1980, before the claims rate fell.

[19] Cherry was writing specifically about the US, but it applied in the UK. “Dr Gerard Vaughan, Minister for Health, pointed out that figures for vaccine damage payments, which involved a retrospective judgement based on the balance of probabilities, could not be taken to give an accurate assessment of the risks of permanent damage,” reported the Times in 1981.

[20] In a 2019 article published in the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society, Cherry reiterated: “The results of a number of controlled studies between 1979 and 2004 indicated that no risk of severe neurologic disease after DTwP vaccinations existed. It was noted by myself and Shields (a pediatric neurologist) that what was being called pertussis vaccine encephalopathy was not an encephalitis-like event, but, instead, the first seizure or seizures of infantile epilepsy.”

[21] Japan had weathered its own pertussis controversy in the 70s, suspending the immunisation programme in 1975, and confronting a deadly epidemic at the decade’s end. But here, an escape-hatch from controversy was closer at hand: scientist Yuji Sato’s acellular vaccine candidate, was already performing well in trials in the 70s. In 1981 it was approved nationally.

[22] Contemporary anti-vaccine politics directly draw on the vaccine-critical agitation of the 1970s. Dissatisfied Parents Together (DTP) became the National Vaccine Information Centre, a group often since accused of spreading misinformation.

More from Maya Prabhu

Recommended for you