Back to basics: the journey of “health for all”

As the delegates to the 76th World Health Assembly convene under the banner “saving lives, driving health for all”, VaccinesWork reflects on the history of an ambitious idea.

- 26 May 2023

- 12 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

China's three-person delegation to the 28th World Health Assembly (WHA), which convened at Geneva's Palais des Nations in May of 1974, included two very different health workers.

The first was Huang Chia-szu, an eminent, excellent, expert figure in the medical hierarchy of the People's Republic: a professor of surgery, practising on the cutting edge – in more than one sense – of curative care, and the President of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

“Technology could not surmount the fact that much of Asia possessed little in the way of rural health services to detect and report cases of malaria.”

– Sunil Amrith, Decolonising Global Health

The second was both his complement and his foil: a part-time farm worker, part-time community medic, a "model worker" representing the one-and-a-half million strong corps of rural Chinese farmer-medics.

The barefoot doctors: "prevention first"

The WHA's records identify her as "Dr Wang Kuei-Chen1, "Barefoot" doctor of Kiang chen People's Commune, Chuan Sha County, Shanghai." But Wang was a physician neither by qualification nor pay-grade. Her medical schooling was most likely limited to between three and six months of basic training, with top-up courses and refresher classes added on – the standard for China's Barefoot Doctor programme – and enough, it appeared, to have made a profound difference to rural health in just nine years of formal existence.

The baseline was profound neglect. In 1949, China was home to 40,000 doctors – some sources say 20,000 – in a population nearing 600 million. Almost all physicians lived in cities; 80% of the population laboured in the countryside.

In 1965, at the dawn of the Cultural Revolution, Chairman Mao ordered an inversion of public health priorities. Twenty percent of China's medical force were sent to rural areas to provide care, but more importantly, to train up a large-scale legion of paramedical rural health workers like Wang.

Credit: Gavi/2023

The barefoot doctors traded in both western and traditional medicine, and adhered to a "prevention first" policy, which Wang outlined at a WHA session on communicable disease control in Geneva, 49 years ago this month.

Prevention, as she explained it, was a safety net woven from multiple fabrics. Health education was one: "As they knew the conditions in the rural areas, [the barefoot doctors] could take advantage of, say, a break in agricultural work in the fields to tell commune members about disease prevention," say the official records of her address.

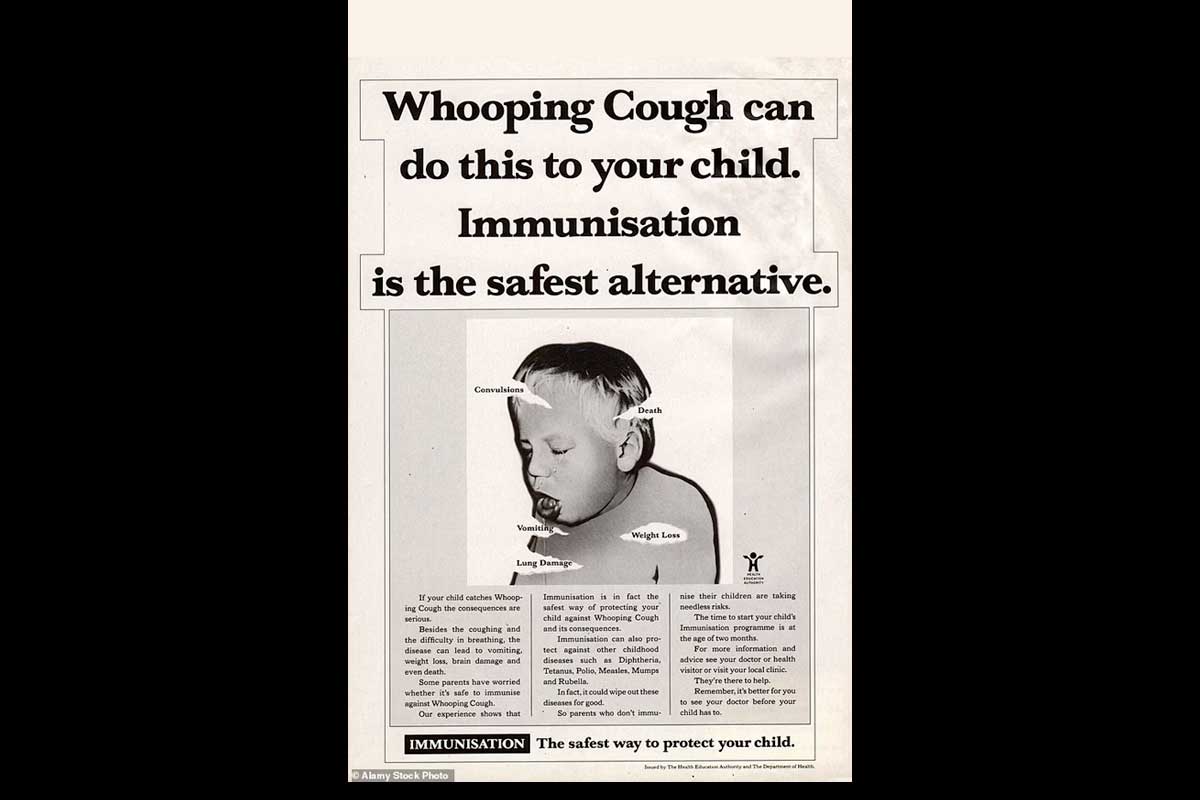

Immunisation – against smallpox, measles, whooping-cough, and epidemic encephalitis B – was another. Coverage rates now stood at 100%, Wang said, and morbidity from infectious disease had consequently fallen3.(For comparison, most developing countries are thought, at this point, to have had immunisation rates of approximately 5% among infants).

The barefoot doctors also periodically mobilised their fellow agricultural workers in "patriotic sanitary campaigns" against pests, like rats, schistosomiasis-spreading snails, and malarial mosquitoes, she told the gathered dignitaries. The disposal of human faecal matter was controlled, swamps and stagnant pools were drained, insecticides sprayed.

One imagines Sri Lanka's delegate, at least, sat up at this. Malaria, target of a resource-intensive, all-out, tech-forward World Health Organization- (WHO-) led "vertical" eradication campaign, which had made astounding inroads in the late '50s and early '60s, was resurging badly by the '70s. "Malaria eradication slipped out of WHO's grasp," reflects historian Sunil Amrith in Decolonising Global Health. "Technology could not surmount the fact that much of Asia possessed little in the way of rural health services to detect and report cases of malaria." In Sri Lanka, Dr Jayasandera told the 28th WHA, the mosquito-borne disease had infected some 217,000 people in 1973 alone.

“Large numbers of the world’s people, perhaps more than half, have no access to health care at all, and for many of the rest, the care they receive does not answer the problems they have.”

– John Bryant, Health and the Developing World, 1975

By contrast to the faltering, almost surgically narrow eradication campaign, what Wang was describing was a radically horizontal, low-tech approach4. The integration of medical, sanitary, and social services, and the integration of the healthcare worker into the community, constituted a mechanism of health care that was, above all else, accessible and affordable.

Proximity – geographic and social – was foundational. The barefoot doctors "treated their patients as their dear ones, and were in turn profoundly welcomed by the peasants," as Wang told her audience. As an idea – at least an ideal – it was thrumming with promise.

Primary health care: "A spiritual and intellectual awakening" – Halfdan Mahler

Even before Wang spoke in Geneva that spring, the Barefoot Doctors programme was emerging as a north star for the burgeoning Primary Health Care (PHC) movement in global health.

The historical moment was baying for new solutions. The tech-led vertical strategies long boosted by the US – this was the Cold War, and even health was foreign policy – were losing their shine, as public health campaigners realised that vanguard medical technologies were a sequestered resource. "Large numbers of the world's people, perhaps more than half, have no access to health care at all, and for many of the rest, the care they receive does not answer the problems they have," wrote John Bryant in his influential 1971 book5 Health and the Developing World.

Credit: Living Goods/2022/Jjumba Martin

Ideologically and pragmatically, China's socialised health care system had struck the leaders of several newly postcolonial, leftist-nationalist African states – vulnerable to infectious diseases and low on funds – as an apt model. A Tanzanian delegation, for instance, visited China in 1967, and left "impressed by the stage of development of health services".6

China, in turn, found that its health system was a compelling exhibition object for the promotion of its world view. Between 1963 and 1989 China sent medical teams to more than 40 countries in Africa7. A first medical delegation from the US visited China in 1971 at the invitation of the China Medical Association. "China's achievement in public health shows that Communist China had more to offer the world," raved E Grey Dimond8, one of the American delegates, on his return.

Have you read?

In 1973, Halfdan Mahler, who had spent time attached to India's National Tuberculosis Programme, was a strong voice for social justice in global health, and who had signalled interest in China's barefoot doctors and analogous community-led health programmes in other developing countries9, was elected Director General of the WHO. In 1975, Mahler proposed the pursuit of "health for all"– a beautiful ambition, and a call-to-arms which still resounds nearly half a century later.

“Of all the interventions of GOBI, immunization achieved the greatest success and prestige.”

– Marcos Cueto

It took a few years of involved diplomatic wrangling, but in 1978 at Alma Ata, consensus – albeit brittle consensus – was met. A global declaration was signed, affirming that health – "which is the complete state of physical, mental and social wellbeing, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity" – was a human right; that health for all by the year 2000 was the goal; and that primary health care was indispensable to its achievement.

This would be more than health policy; PHC would function as the core of all social and economic development.

"Primary health care is essential health care based on practical, scientifically sound and socially acceptable methods and technology made universally accessible to individuals and families in the community through their full participation and at a cost that the community and country can afford to maintain at every stage of their development in the spirit of self-reliance and self-determination," Article V of the Alma Ata Declaration.

"At the end of the conference, a young African woman physician in beautiful African garb read out the Declaration of Alma-Ata. Lots of people had tears in their eyes," recalled Halfdan Mahler in 2008. "That was a sacred moment."

Erosion

Without question, Alma-Ata had weaknesses – for good and ill, it was idealistic and very big; 2000 was a too-tight deadline; it was thin on measurements for progress; it read 'community health' (including the barefoot doctors) a little simplistically, maybe even superficially10 – but it also had bad luck. The 1980s came on awfully quickly.

Margaret Thatcher was in office before the turn of the decade; Ronald Reagan was inaugurated in 1981. Conservatism and a neoliberal zeal for the market's appetites were in ascendancy. The post-war energy for international cooperation dimmed; Reagan withdrew from UNESCO and threatened to leave WHO.

Already in 1979, a number of agencies led by the Rockefeller Foundation convened to trim down Alma-Ata in the name of realism. The modified proposal that emerged was called Selective Primary Health Care (SPHC) – "for supporters… the minimum package of health care services that was possible to provide to the poor," in Marcos Cueto's words – and, as public sector ambition retracted, it rapidly overtook its expansive, generous parent.

UNICEF's take on SPHC gained particular traction. Its flagship offering was a four-intervention package, described by the acronym GOBI: growth monitoring, oral rehydration techniques for diarrhoeal disease, breast feeding, and immunisation.

"Of all the interventions of GOBI, immunization achieved the greatest success and prestige," writes Cueto. WHO launched the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) in in 1974. By 1989, WHO could boast that half of the children in the developing world received immunisation each year. "This partially occurred because new immunization programs paid due attention to community participation and education and was no longer pledged to a rigid 'top-down' design."

Credit: Gavi/2018/Guido Dingemans

In China, the rout of the primary health care model was more complete. In the 1980s, China too swivelled towards the market and away from its Maoist collective economic system, which had paid the salaries of the barefoot doctors. The programme was disbanded. Jobless, barefoot doctors opened private practices and charged user fees. "It seemed highly ironic that by the mid-1980s, millions of rural villagers in China, once the world leader in Primary Health Care, were left without healthcare," writes Xun Zhou.

Recommitment

Despite the challenges to Alma-Ata's ideals, the achievements of PHC in the last half-century are particularly easy to appreciate from the vantage point of immunisation programmes around the world. Picture a vaccination outreach worker with a blue vaccine cooler-box dangling from one shoulder, and you're picturing an inheritor of the barefoot doctor's legacy. India's million-strong legion of ASHA workers, Pakistan's Lady Health Workers – vital nodes in their respective national immunisation systems – are transformative examples of PHC in action. There are many others.

![Rural health care. Left - a barefoot doctor in a cotton farming commune, eastern PRC, 1975 (still from a documentary [link] by Diana Li). Right - Nurses deliver COVID-19 vaccines in the Sundarbans, India, 2021"](/sites/default/files/vaccineswork/2023/Thumbnail/side-by-side_h2.jpg)

Left - a barefoot doctor in a cotton farming commune, eastern PRC, 1975

(still from a documentary by Diana Li.)

Right - Nurses deliver COVID-19 vaccines in the Sundarbans, India, 2021.

Credit: Gavi/2022/Benedikt v.Loebell

And in the last couple of decades, the global health community has turned freshly appreciative eyes on the principles articulated at Alma-Ata. A 2008 Lancet special issue reflecting on the Declaration at 30 determined it, broadly, still relevant, still vital.

A comment piece in the issue by Margaret Chan, then-DG of WHO, made a bid to rehabilitate its ideals. "With an emphasis on local ownership, primary health care honoured the resilience and ingenuity of the human spirit and made space for solutions created by communities, owned by them, and sustained by them," she wrote. "The approach was almost immediately misunderstood. It was a radical attack on the medical establishment. It was utopian. It was confused with an exclusive focus on first-level care. For some proponents of development, it appeared cheap: poor care for poor people, a second-rate solution for developing countries. … Today, primary health care is no longer so deeply misunderstood."

New immunization programs paid due attention to community participation and education and was no longer pledged to a rigid “top-down” design.”

– Marcos Cueto

Ten years later, world and health leaders met at Astana to reaffirm "the commitments expressed in the ambitious and visionary Declaration of Alma-Ata of 1978 and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, in pursuit of Health for All". A year after that, at a first UN high-level meeting on Universal Health Coverage, world leaders pledged that "the highest attainable standard of health" was a human right, and recognised primary health care as "the most inclusive, effective and efficient approach to enhance people's physical and mental health".

Credit: Gavi/2022/Asad Zaidi

The ongoing 76th World Health Assembly convenes in the light of those promises, under a familiar-sounding banner: "saving lives, driving health for all."

It is also the first WHA to succeed the COVID-19 emergency. The world responded to the novel pandemic virus at staggering speed. But emergencies are vertical, and jealously vertical, by nature. More than 13 billion COVID-19 vaccine doses have been administered worldwide, but in 2021 alone, 25 million children missed out on at least one routine vaccination. In the 57 Gavi-supported countries, the number of unvaccinated 'zero-dose' children swelled to 12.5 million; globally, it reached 18.2 million.

“History has shown us that there really is no “health for all” without immunisation for all … Vaccine equity opens doors to inclusive, equitable primary health care, and is essential for universal health coverage.”

- Anamaria Bejar, Director of Public Policy Engagement, Gavi

"Primary Health Care is a global commitment that should be realised and funded as a matter of urgency. To honour the 'barefoot doctors' still making a big difference in communities all over the world – the majority of them women – and to reach zero dose children, we need to reflect on a critical question: what does the road to health equity and health justice look like look like in today's world?" said Anamaria Bejar, Gavi's Director of Public Policy Engagement. "Two things are clear: firstly, history has shown us that there really is no 'health for all' without immunisation for all. Secondly, vaccine equity opens doors to inclusive, equitable primary health care and is essential for universal health coverage."

1. More commonly spelled Wang Guizhen

2. Just how transformational the Barefoot Doctor programme was to Chinese health is contested. The CPC heavily promoted claims that the rural health system totally eradicated the previously highly prevalent parasitic infection schistosomiasis. This headline achievement has been refuted as overblown. There is evidence that some barefoot doctors in some areas were too meagrely trained to be effective, as historian Xun Zhou of the University of Essex has pointed out – but “many barefoot doctors did provide invaluable healthcare or aid for millions of villagers in the rural countryside”, she concludes.

3. “The mortality rates of infectious disease started declining after 1968 and dropped to their lowest ever levels by 1970, where they have remained ever since,” writes Xiaoping Fang, noting that vaccines against the deadliest infectious illnesses were being produced in China by 1970.

4. Not that the PRC had eschewed forward-facing research science. In fact, just three years before Wang attended the WHA, Tu Youyou had become the first researcher to isolate artemisinin from sweet wormwood – a compound that WHO now recommends as part of the principal treatment for falciparum malaria. Tu was awarded the Nobel Prize for her discovery in 2015.

5. For a proposed bibliography of literature foundational to 1970s PHC thinking, see Dr Socrates Litsios's chapter in Health for All: the Journey of Universal Health Coverage.

6. John Iliffe, East African Doctors: A History of the Modern Profession, quoted in Xun Zhou "From China's "Barefoot Doctor" to Alma Ata: The Primary Health Care Movement in the Long 1970s."

7. Xun Zhou, "From China's "Barefoot Doctor" to Alma Ata"

8. E Grey Dimond, "More than Herbs and Acupuncture," Saturday Review (December 18, 1971), quoted in Xun Zhou, "From China's "Barefoot Doctor" to Alma Ata"

9. The Barefoot Doctors program was not alone in inspiring WHO-led conceptions of Primary Health Care – but it was probably the single greatest influence on the from PHC took by Alma-Ata. Interested readers might begin to read more about other early rural health development experiences in ""Health for All".

10. Marcus Cueto has more.