5 ancient diseases and what the ancients said about them

Maybe more surprising than a 4,000-year-old prescription for ‘extract of crocodile’ or a 2,600-year-old warning that sex after rich food can cause leprosy, is how much the ancient medics got right.

- 21 September 2022

- 12 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

The genetic record confirms that many of our common infectious scourges have roots in antiquity. DNA samples from the leg bones of a Roman skeleton unearthed at Lugnano, Italy, for instance, proved that falciparum malaria had ravaged the sixth-century community. Using molecular clock modelling, scientists are able to peer even further into the past, poring over pathogens’ evolutionary histories, revealing, for example, that the divergence of the human measles virus from the cattle bug rinderpest occurred way back in the sixth century BCE.

“Oh! my Father! Concerning a man whom […] a rabid dog attacks, and to whom passes its venom […], I do not know what I shall do for that man.” Marduk, Akkadian God of Healing, c. 21st century BCE.

But genetic analysis tells us nothing about how the ancients understood the diseases that sickened and killed them, or how they tried to ease or resolve their symptoms. For that, we need to dig into the written record.

The maladies and visitations referenced in the world’s oldest surviving medical texts are sometimes hard to identify – systemic, scientific lists of symptoms are not always on offer; an objective clinical picture might be muddied by assumptions about demonic or divine intervention. But sometimes, the diagnosis leaps off the page, the illness recognisable by its still-familiar characteristics.

Here are five diseases from deep in the historic record – all of which we still battle today.

MALARIA

What we know now

Transmitted by the bite of the female Anopheles mosquito, the malaria parasite remains the cause of more than 620,000 deaths a year, the vast majority of those in children under the age of five.

That’s despite the fact that humanity has been hunting for the means to prevent and turn back the infection for millennia, and despite the fact that many good preventive tools and life-saving drugs now exist.

From bed-nets and mosquito sprays, to chemoprevention and treatments, that varied arsenal saves millions of lives each year. Last year, it received an important addition: in late 2021, the Gavi Board decided to fund the world’s first malaria vaccine rollout, marking a new, and hopefully transformative chapter in an age-old fight.

What they knew… in Ancient China

In Chinese medical documents of 270 BCE, tertian (every third day) and quartan (every fourth day) fevers presenting with the characteristic enlarged spleen are clearly recognisable as malaria. The headaches, chills and fevers were attributed to the interference of three demons: one with a hammer, one with a bucket of water, and one with a stove.

If that demonic aetiology seems quaint, the remedy proposed by the philosopher and medical thinker Ge Hong half a millennium later is surprisingly current. Written in ca. 340 CE, his Handbook of Prescriptions of Emergency Treatments offers a preparation against such ‘intermittent fevers’ which has leapfrogged into modernity.

Credit: Gan Bozong (Tang period, 618-907)

“Take a handful of sweet wormwood,” wrote Ge Hong, “soak it in a sheng of water, squeeze out the juice and drink it all.”

In the 1970s, Chinese scientist Tu Youyou took up his advice, and began to investigate the curative properties of sweet wormwood. It didn’t take long for her to isolate the antimalarial compound artemisininfrom the plant, a discovery which won Tu Youyou the Nobel Prize in 2015. Today, WHO recommends artemisinin combination therapy as the first line of defence against uncomplicated cases of falciparum malaria, the deadliest strain.

TUBERCULOSIS

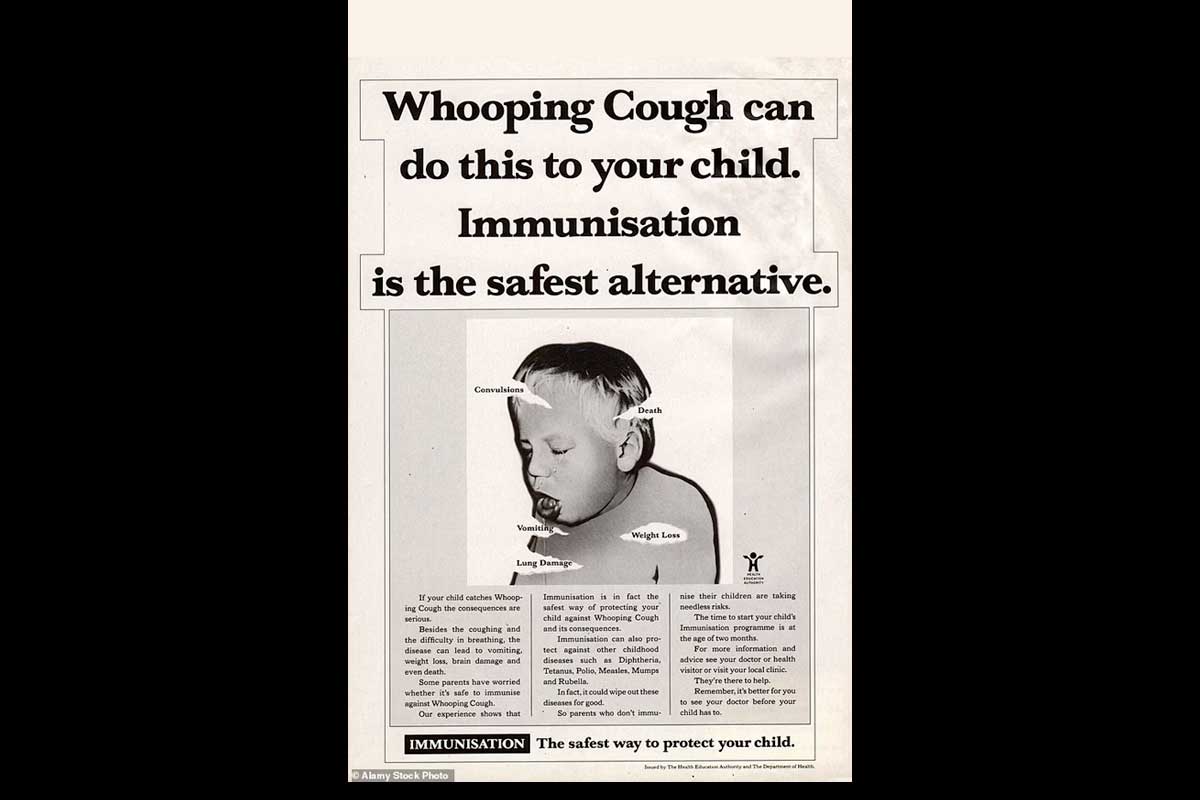

What we know now

Every year 10 million people get sick with tuberculosis, a bacterial infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis which most commonly affects the lungs. Of those, 1.5 million die. Most cases of TB are curable with the use of antibiotics, but multidrug-resistant TB is a growing health crisis.

The disease spreads through the air. When people with TB cough, sneeze or spit, germs are released which are capable of hovering for several hours. Inhaling just a few of the bacteria can be enough to cause infection to take root – though only 5-10% of people infected with TB bacteria will become sick.

Untreated, 45% of people with TB will die – usually after a period of weight loss, violent coughing that brings up sputum and blood, night sweats and fever. Among HIV-positive people, that number rises to almost 100%. Though the tuberculosis pathogen wasn’t discovered until 1882 – at which time TB killed one in seven people in the US and Europe – it’s been with us for possibly as long as three million years.

Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

In 1921, Albert Calmette and Jean-Marie Camille Guerin developed the Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine against tuberculosis, still the only vaccine in widespread use today. It was a vital milestone in the fight against the illness, but the BCG vaccine wears off over time, and has limited efficacy in adults. New vaccines are in development.

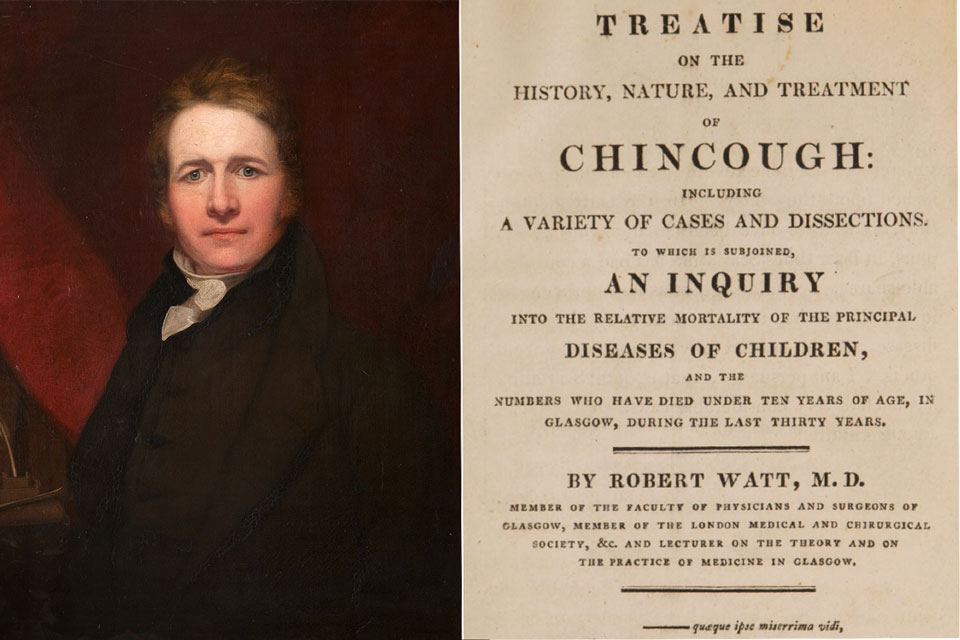

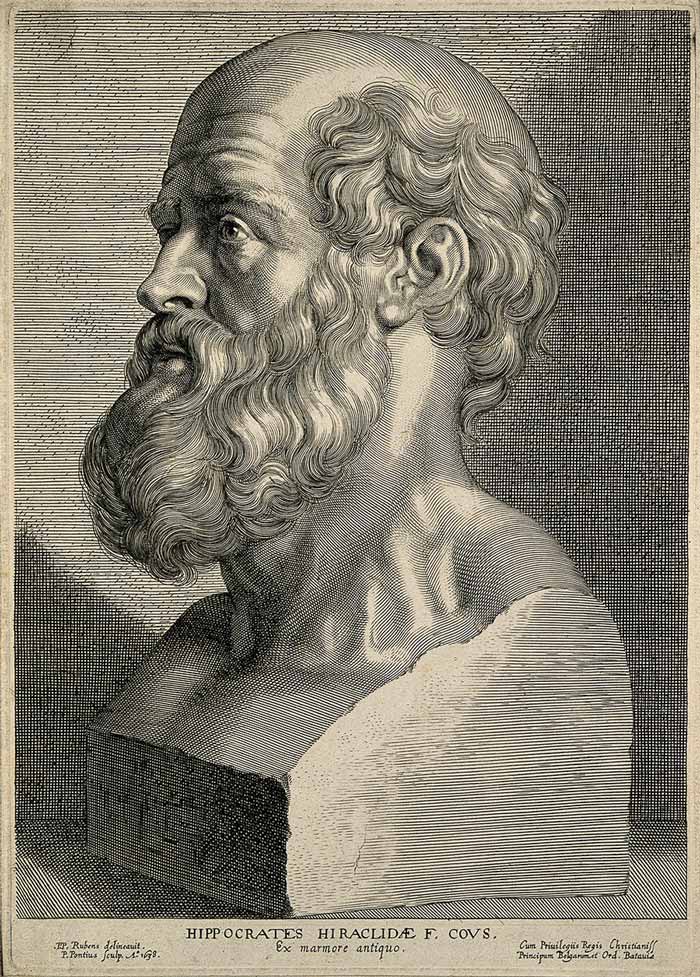

What they knew… in Ancient Greece

It was tabesto ancient Romans, and schachepeth in ancient Hebrew. Known as phthisis in ancient Greece, tuberculosis was described by Hippocrates, writing in about 400 BCE, as a wasting disease accompanied by cough, spit and fever, and which “made its attacks chiefly between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five” – a finding consistent with modern observations of a tendency for active tuberculosis to hit young adults.

“Those who spit up frothy blood bring this up from the lung,” he understood, warning his students against taking on advanced cases: they were likely to die, he said, and could tarnish the treating physician’s reputation.

Have you read?

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images images@wellcome.ac.uk http://wellcomeimages.org Hippocrates.

Hippocrates’s self-appointed Roman heir, Galen, incorrectly imagined TB as a process of blood leaking out of the lung into the chest, and recommended fresh air, milk, and sea voyages, a prescription which echoes the 19th and 20th century medical habit of sending consumptives to ‘take the air’ at mountain or seaside sanatoria.

The Hippocratic theory of disease, which understood illness as an imbalance of the four humours of the body, did not offer an explanatory concept for epidemic transmission. However the Hippocratic writers did note, in Book I, Of the Epidemics that tuberculosis “was the most considerable of the diseases which then prevailed, and the only one which proved fatal to many persons.” That grim reputation still resounds today, with TB having lost its status as the world’s deadliest infectious disease only with the arrival of COVID-19.

RABIES

What we know now

Caused by a virus that spreads by the bite of an infected animal – 99% of the time, a dog – rabies has been vaccine-preventable for more than a century, but continues to kill thousands of people each year, 95% of them in Asia and Africa.

There is no treatment. The virus travels in the nervous system, remaining undetectable in the blood until almost the end. Once the first symptoms set in – usually two to three months after exposure, but sometimes as long as a year – death is virtually guaranteed. The disease’s days-long progression is a notorious horror. In its more common form, known as ‘furious rabies’, hyperactivity, excitability and aggression, hydrophobia, and aerophobia precede death by cardio-respiratory arrest. Paralytic rabies moves more slowly, with a gradual paralysis spreading from the site of the bite. It’s usually only conclusively diagnosed after death, and as such, is often misdiagnosed.

But the rabies vaccine – developed in its first form by Louis Pasteur in the 1880s – is almost universally effective when deployed correctly as part of a post-exposure prophylactic protocol, with the first dose administered ideally on the day of exposure.

Further, the canine vaccine has wiped out the virus as a public health threat in most wealthier countries, and is making major strides in parts of the world’s most rabies-vulnerable countries.

What they knew… in Ancient Mesopotamia

Rabies, which diverse cultures have understood as nothing short of the dissolution of a bite victim’s humanity, his perversion to a bestial state, is relatively thick on the ground in surviving ancient texts.

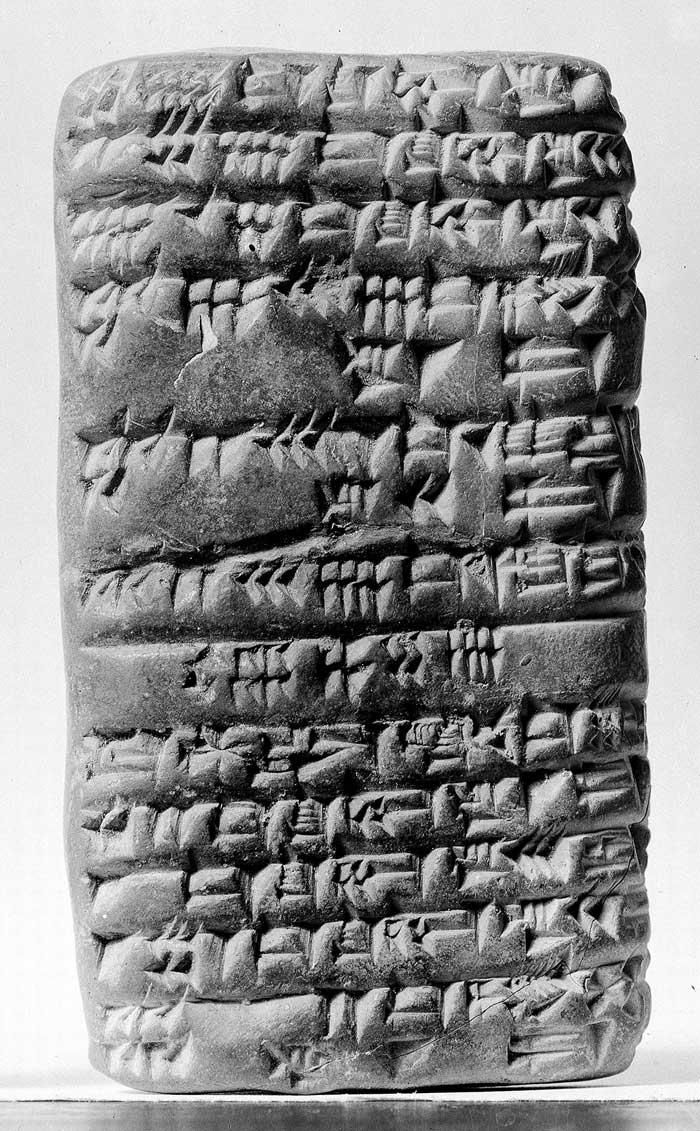

Some of the earliest references are over 4000 years old. Akkadian clay tablets of incantations from the ancient city-state of Ur, unearthed in modern-day Nuffar, Iraq and dated to ca. 2100-2000 BCE, include a fascinating exchange between Marduk, the God of Healing and his father Enki. Striking is the tone of despair – the suggestion of even divine impotence in the face of the still-now incurable disease: “Oh! my Father! Concerning a man whom […] a rabid dog attacks, and to whom passes its venom […], I do not know what I shall do for that man,” Marduk admits.

It’s striking that Akkadian “dog-bite incantations” – chanted during a quasi-medical ritual usually reserved for only the most serious illnesses – regularly refer to the dog’s saliva (which we know today to be the vehicle for the virus’s transmission) as “venom”, comparable to a snake’s or a scorpion’s.

One incantation from ca. 1900-1600 BCE hints at the disease process which follows as a sort of hybridisation: The rabid dog’s “semen is carried in its mouth”, it says. “Where it has bitten, it has left its child.”

Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

The Sumerian laws of Eshnunna, from ca. 1930 BCE, identify the dog’s bite unambiguously – and culpably – as the direct cause of mortal human illness. A man who did not watch over his rabid dog allowing him “to bite a man and cause his death”, the laws stipulate, must be fined in shekels of silver (a discounted rate applied when the victim was a slave).

LEPROSY

What we know now

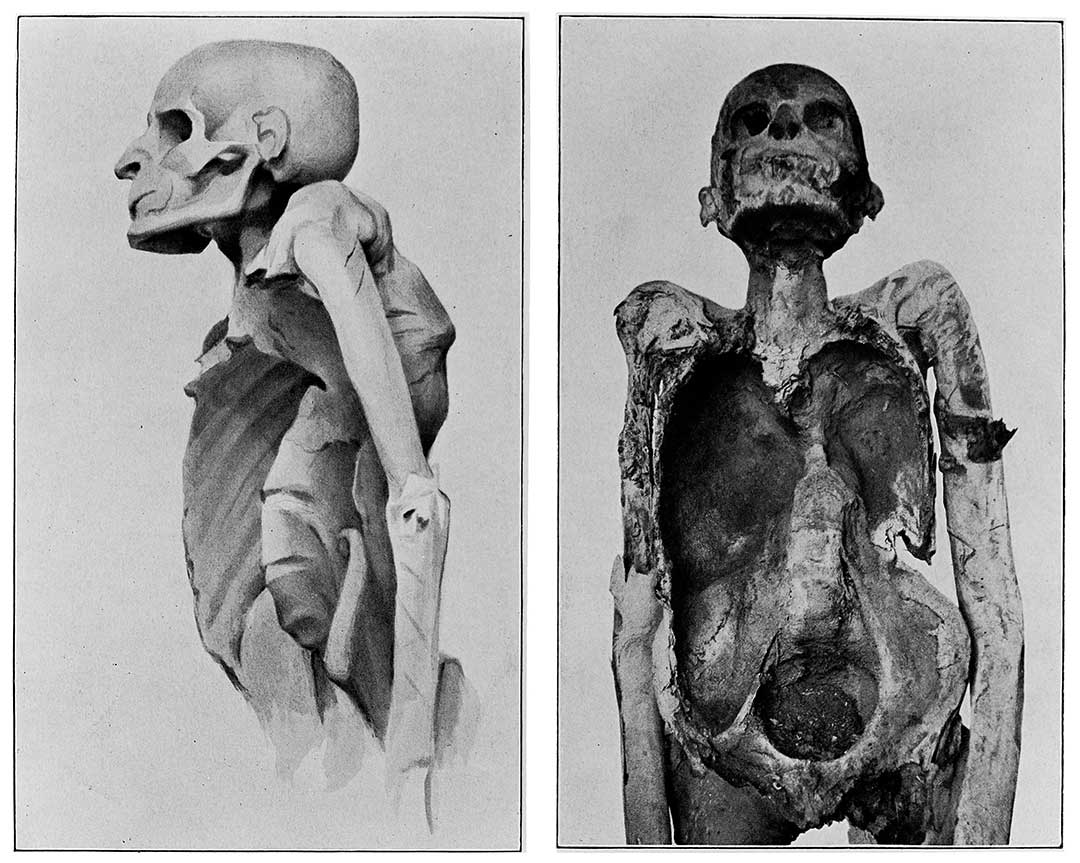

A chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae, a slow-growing, slow-spreading bacterium, leprosy affects the skin and nerves, the eyes, and the mucosa of the upper respiratory tract. Since the 1980s, the infection has been curable with a year-long course of multi-drug therapy (MDT). But if detection and treatment are delayed, the nerve damage and other disabilities resultant from the infection might be permanent – and even progressive. Where nerves have been damaged and limbs numbed, sufferers continue to be prone to new injuries, which, unfelt, can become terribly infected.

In 2020, 7,198 of the world’s 127,558 new leprosy patients had already progressed to severe, permanent disability before they were identified and treated. Though forced transferral to ‘leper colonies’ is a public health strategy from a crueller past, leprosy remains a diagnosis freighted with a profound and isolating social stigma.

What they knew… in Ancient India

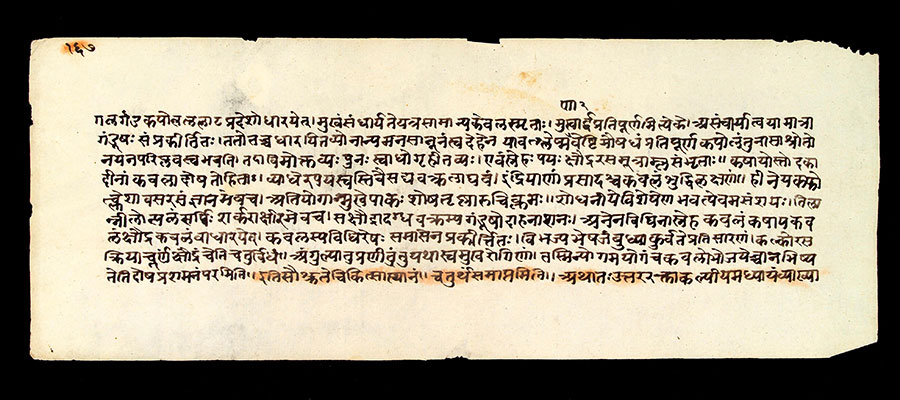

Leprosy is referenced in Egyptian scrolls and Indian vedic texts from as long ago as 1550 BCE, but some scholars consider that the first clinical portrait of the chronic infection arrived with the Sushruta Samhita, a Sanskrit treatise on medicine and surgery from perhaps 600 BCE (though there’s considerable disagreement about temporal origin).

Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

It was a ‘maha kushtha,’ or great skin disease, characterised by vermillion-coloured patches, numbness, deformity of the limbs, suppuration of the affected parts, the falling off of fingers, the sinking of the nose. Long before germ theory revolutionised how we understood contagion, the author or authors called Suśruta understood that diseases, including leprosy, could transfer by proximity: “Leprosy, fever, consumption, diseases of the eye and other infectious diseases spread from one person to another by sexual union, physical contact, eating together, sleeping together, sitting together, and the use of the same clothes, garlands and pastes.”

Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

But it was also described as a kind of karmic visitation, a punishment: “It is said that acts of killing a Brahmin, a woman, or a noble person and usurpation of other’s money, etc., are responsible for leprosy, which is a disease born out of sins.” Rebirth was no escape: leprosy sufferers would be afflicted again in their next life, Suśruta wrote. It was also a more worldly inheritance, he thought, capable of passing from father and mother to child via the semen and menstrual blood.

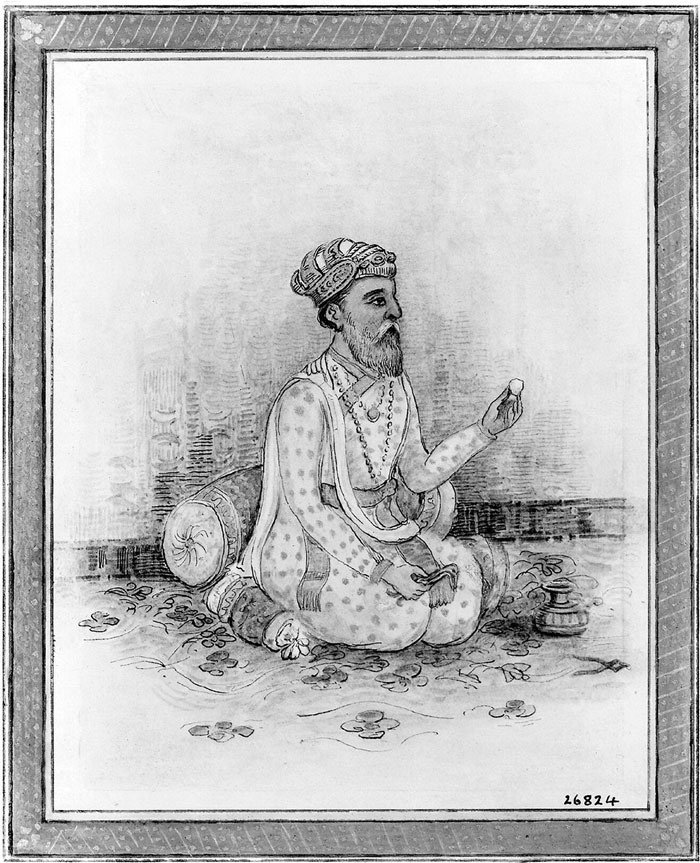

In about 78 CE (again, the timelines are debated), the Emperor’s physician, Charaka, produced his own magnum opus, the Charaka Samhita. In this great medical text, seven varieties of leprosy are identified, of which just one is incurable.

Charaka’s aetiological explanations are less metaphysical, but no less wrong: sudden changes in diet during the seasons’ changes could excite a leprosy, he thought; as could sudden plunging into cold water while afraid, or grieved or exhausted, or sex after eating too much rich food.

A remedy which first entered the historical record with the Ayurveda Susruta (100-900 CE) and still recommended in India by traditional practitioners is Tuvarka seed oil, either consumed, or rubbed onto the affected regions.

TRACHOMA

What we know now

The bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis evolved into a pre-human world, one populated by strange little early mammals. Genital strains of the bug emerged first; the ocular strains diverged from them two to five million years ago. Modern humans – young, by contrast – joined the chlamydia bug on earth 120,000 years ago.

Today, trachoma remains the leading infectious cause of blindness in the world. It can be spread by the ocular and nasal discharge, directly, and can also be carried from person to person on the bodies of flies. Classed as a Neglected Tropical Disease, trachoma is a public health problem in 44 countries. In endemic areas, inflammatory trachoma is common among small children, but repeat infections can cause the inside of the eyelid to become so scarred that it turns inwards in a painful process called trichiasis, in which the eyelashes scrub against the eyeball, risking corneal scarring and irreversible blindness.

© Clare Gilbert. Published by the International Centre for Eye Health www.iceh.org.uk, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

In 2020, 42,045 people received surgery for the advanced stage (trachomatous trichiasis) of the disease.

What they knew… in Ancient Egypt

In ca. 1600 BCE, a thousand years after trachoma’s very first appearance in the written record – via an entry in the Chinese text Huang Ti Nei Ching (ca. 2700 BCE) – the blinding infection entered the medical canon of ancient Egypt.

Source: Tomb chapel of paätenemheb (RMO Leiden egypt saqqara 1333-1307bc)

Two documents commonly referred to as the Edwin Smith papyrus (ca. 1600 BCE – thought to be copied from a text produced around 3000 BCE) and the Ebers papyrus (ca 1550 BCE) discuss acute and chronic eye blurriness and blindness. The causative diseases are hard to separate out with perfect clarity, but most historians agree that they include trachoma, a sickness which retained its association with the people of the upper Nile, becoming known in modernity as ‘Egyptian eye disease’.

A diverse parcel of remedies is recorded. If trichiasis occurred, the eyelashes were supposed to be removed. To prevent recurrence, the papyri call for treatment with ointments applied, usually, to the outside of the eyes. These consisted of oils or fats mixed with fragrant compounds like myrrh and resin, or grated minerals like malachite, green copper carbonate, and red natron. Honey, thought then to have an effect on demons, but in fact also a natural bactericide, was frequently stirred in.

“The characteristic black or – sometimes – green painting of the eyelids and margins was not only a sacred rite… but part of a more or less rational treatment involving antibiotic elements such as allicin from garlic,” writes S. Ry Anderson of the Eye Pathology Institute of Copenhagen.

Other treatments sound more outlandish: it’s hard to imagine “extract from crocodile” or “gall from fish” or “extract from healthy pig eyes” having powerful healing properties, and honey probably didn’t do its best work to resolve eye problems when it was funnelled into the patient’s ear.

So: were the remedies effective? Anderson suggests we have to be careful in dismissing them out of hand. Copper, for instance, mentioned in the scrolls, would have had a chance of changing the course of the trachoma infection. “The psychological placebo effect is undoubtedly the greatest, whatever the method used, apart from some minor surgical treatments such as epilation,” he concludes.