The female bridge: How a new link in the healthcare chain helps vaccines reach kids in under-immunised Lakki Marwat

In a culturally conservative part of north western Pakistan, mothers were disconnected from a very male healthcare system until female community workers – like Nusrat Bibi – built a bridge.

- 19 April 2022

- 6 min read

- by Huma Khawar

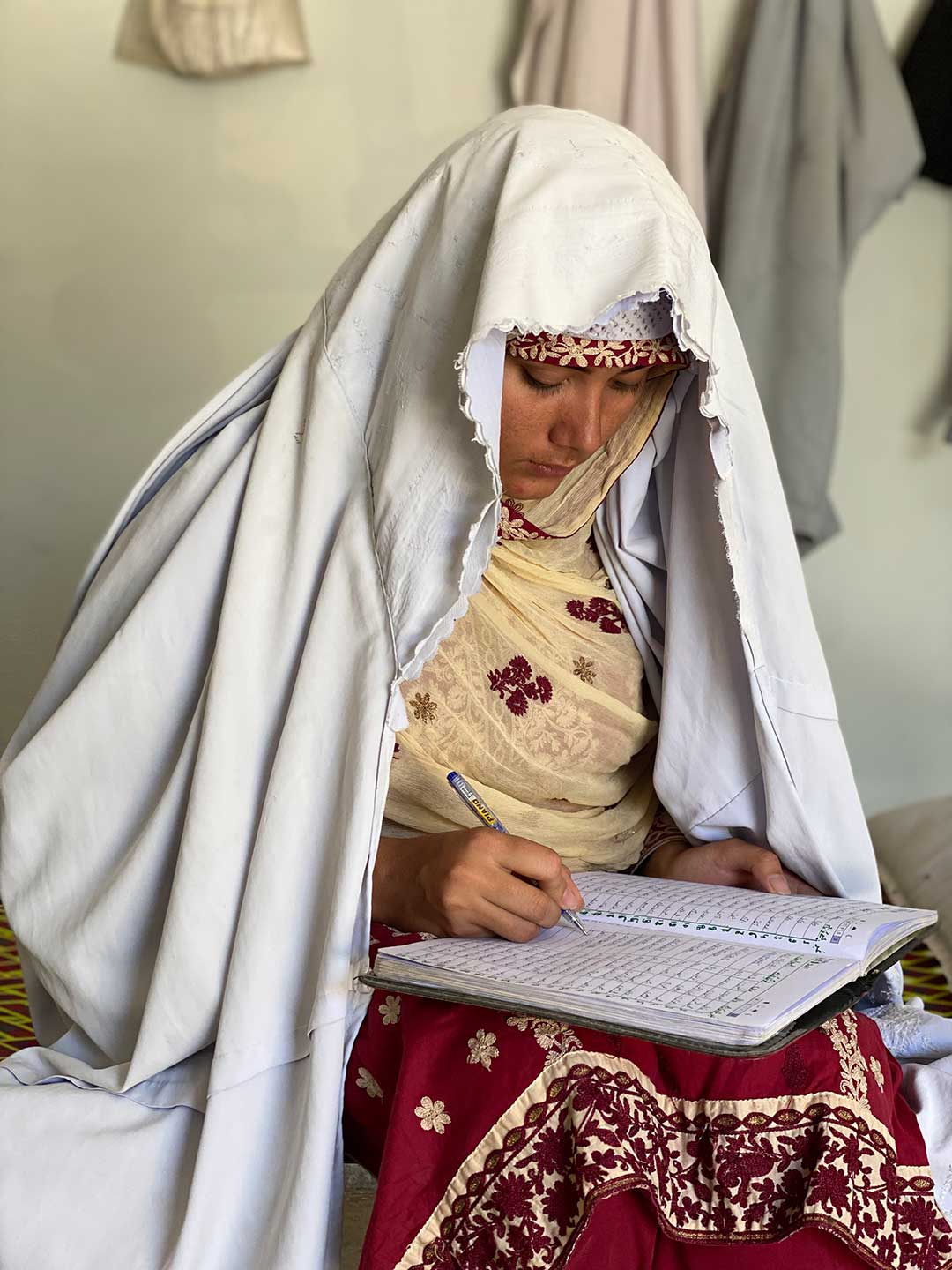

It’s a warm April morning on the sandy plains of Lakki Marwat in Pakistan’s northwestern Khyber Pakhtukhwa. In a village called Masha Mansoor, some 20 women have gathered in the drawing room of a community elder. The room, known locally as a hujra, is a space usually reserved for men and, though this meeting is an all-female, informal affair, some of the women have kept their burqas on – a visual reminder, to outsider eyes, that Lakki Marwat is perhaps the most conservative part of an especially conservative province.

Credit: Huma Khawar

Lakki Marwat district can claim only 29 percent full immunisation coverage among under-twos. Of the remaining 71 percent of kids who have missed out on routine jabs, a staggering 51 percent count as zero-dose children

Nusrat Bibi, 21, stands to address the group. Her voice, speaking the local Pashto, is warm; her manner open and friendly. What are some of the reasons, she inquires, that the women gathered have chosen not to vaccinate their children against preventable childhood illnesses?

Credit: Huma Khawar

It’s a pressing question, even if she asks it unhurriedly. As the village’s Community Resource Person (CRP), a kind of adjunct non-medical figure in the local health system, Nusrat knows that Lakki Marwat is lagging dangerously behind on immunisation coverage.

While 76.1% of Pakistani children aged under two qualify as fully vaccinated, those children are not evenly distributed across the vast and varied country. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa trails the national average, recording an overall vaccination rate of 68 percent. Within the state, the arid south sees the lowest immunisation coverage and Lakki Marwat district can claim only 29 percent full immunisation coverage among under-twos. Of the remaining 71 percent of kids who have missed out on routine jabs, a staggering 51 percent count as zero-dose children – children who have never received a single vaccine and are, as such, totally vulnerable to preventable infections1.

Credit: Huma Khawar

Thirty-five-year-old Mariyum Begum’s kids number among them. At the Masha Mansoor meeting, Begum volunteers an answer to Nusrat's question. “My husband says [vaccination] is a conspiracy by the West to halt the Muslim population and kill our children,” she says. Nusrat listens quietly, and then explains what vaccines are, and that she wants them to understand that vaccines will protect their children from infection with serious illnesses.

The reasons parents resist vaccination on behalf of their children are individual. But “zero-dose” bubbles – whole communities of unimmunised or under-immunised children – are likely to emerge as a consequence of shared, and often structural, conditions.

“The problem of vaccine hesitancy stems from illiteracy, which gives birth to misconceptions. One-on-one communication helps in shattering the myths around vaccination.”

– Nusrat Bibi

What happens, for instance, when a community’s social life is arranged along such strictly gendered lines that mothers rarely encounter the outposts of public health and health education? Vaccinators and doctors in this region are almost always men. Might the resultant communication vacuum explain why worrying myths about vaccination – such as the one Mariyum's husband articulates – are able to gain uncommon traction?

Have you read?

That’s what the Civil Society Human and Institutional Development Programme (CHIP), an NGO supported by Gavi, was betting when they trained up Nusrat and her fellow CRPs in the villages of Lakki Marwat. “Because of the strict purdah, it is not culturally appropriate for women to interact with unknown men, and it is impossible for men to enter their homes if their male family members are not present,” explains Atif Iqbal, a CHIP project officer.

Credit: Huma Khawar

Nusrat, who comes from a relatively liberal family and remains, unusually, unwed and childless at 21, functions as a “bridge” – a culturally acceptable female interlocutor who can link women up to a health establishment that remains too male to be accessible. Sometimes, that means knocking on doors to let families know that the vaccinator from the district health office is in town, setting up his makeshift walk-in clinic in a neighbour’s hujra. Other times, like today, that means gathering women together for a session of friendly myth-busting.

“The problem of vaccine hesitancy stems from illiteracy, which gives birth to misconceptions,” Nusrat tells VaccinesWork. “One-on-one communication helps in shattering the myths around vaccination.”

For Mariyum, that’s clearly true. Following the April gathering in the Masha Mansoor hujra, Mariyum declares that she intends to get her sons vaccinated. “I think what scared me the most was when Bibi told me my kids could get paralysed if they are not vaccinated,” she says.

The logistics of vaccine delivery can be almost as tricky as convincing parents that vaccination is a good idea. “If women do not want to visit these [makeshift] centres, our female CRPs will pick their kids from their homes and drop them back after getting vaccinated, making sure not to miss the opportunity.”

– Atif Iqbal, CHIP project officer

Another mother at the meeting, 25-year-old Bilquis Jan, travelled over from the nearby village of Samandi. Jan had four kids, none of whom had received a single vaccine, Nusrat Bibi knew. Given that the children were healthy, their parents assumed there was no call for medical intervention. Nusrat has made several home visits over the past three months to explain the prophylactic function of the jabs. “We had heard of some diseases, but not all – and only recently found out that there is a medicine that is injected into a child’s body to fight diseases even before the child is actually ill,” Jan concedes when she speaks to the gathered group.

Bilquis' turnaround, Nusrat later says, appeared to have a catalytic effect. “As she announced that she was ready to get her son vaccinated, more mothers seemed amenable to the idea.”

A big win – but still only half the battle. The logistics of vaccine delivery can be almost as tricky as convincing parents that vaccination is a good idea. “If women do not want to visit these [makeshift] centres, our female CRPs will pick their kids from their homes and drop them back after getting vaccinated, making sure not to miss the opportunity,” says CHIP’s Iqbal.

“This may sound like a pretty straightforward job, but what it takes to get it done is not. Reaching every child requires hard work, meticulous planning, and patience,” says Alvina Gul, a CRP working in Dabak Mandra Khel, a village nine kilometres from Lakki city centre. “Behavioural change almost always requires personal contact,” she says, describing repeated visits and meetings with mothers and mothers-in-law.

“Just when you think you have won [parents] over, you get a setback as they won’t turn up at the centre to get the child vaccinated. You go to their home, and they offer some excuse or another.” The no-shows are often not about resurgent vaccine anxiety, she says, but about life getting in the way – competing priorities, the burden of housework, the shortage of time.

So Alvina puts in the extra miles to bridge the gap between good intentions and good outcomes, visiting 14 to 15 homes each day. “Getting the zero-dose children vaccinated is a cause for celebration for us,” she explains. “We have covered more than four hundred zero-dose children in the last three months in these Union Councils of Lakki Marwat,” she adds, beaming ¬– and says she’s confident that she and her colleagues can convince the rest.

1. Statistics from the most recent Third-Party Verification Immunisation Coverage Survey (TPVICS)

More from Huma Khawar

Recommended for you