“Pakistan can”: How one country repaired its routine immunisation safety net

As the COVID-19 pandemic hit in early 2020, Pakistan’s routine immunisation programme took a heavy hit. But while many countries continued to struggle to make up lost ground in 2021, Pakistan bounced back to pre-pandemic levels of protection. VaccinesWork spoke to country health leaders to find out what went right.

- 11 August 2022

- 8 min read

- by Huma Khawar , Maya Prabhu

New data confirms what public health officials hoped was true: in 2021, Pakistan’s children were very nearly as well-protected against preventable diseases as they had been in 2019. That may not sound like a landmark triumph, but it is – and here’s why.

Like in most countries, routine immunisation in Pakistan suffered a gut-punch – if not quite a knockout blow – when the pandemic landed in early 2020. Mario Jimenez, who has worked on Gavi’s Pakistan programme since 2019, says, “The lockdowns started, and that led to the immediate stop of outreach activities, and a subsequent accumulation of children that were not being reached with routine immunisation.”

“Our biggest fear was to start seeing a massive increase of outbreaks for measles, diphtheria or pertussis, particularly amongst the most vulnerable populations,” Jimenez says. “We felt it was becoming a time-bomb."

Even once the lockdowns lifted, recalls Dr Faisal Sultan, former Special Assistant to the Prime Minister on Health, fear of infection continued to inhibit contact between people and the health system. And even making it to the clinic didn’t always mean a child would get their jab: Pakistan struggled with periodic vaccine stock-outs as shipping and air travel stumbled to a halt globally.

“It really pushed the country and ourselves to reflect about how we can adapt to the situation, and what can be done to recover some of the losses that were taking place,” says Jimenez. These were urgent conversations: the real-world danger signalled by those losses was plain to everyone involved.

Pakistan has a massive birth cohort – more than 16,000 children are born each day. “In a matter of days,” Jimenez says, “we could have a very large number of unprotected unvaccinated children.” With the vaccine levee crumbling, every small disease outbreak risked becoming an epidemic flash-flood.

From July 2020, the health system kicked into high gear, beefing up outreach, and finding novel means to trace unvaccinated “zero-dose” children. Life-saving gains were made.

Credit: Gavi/2020/Asad Zaidi

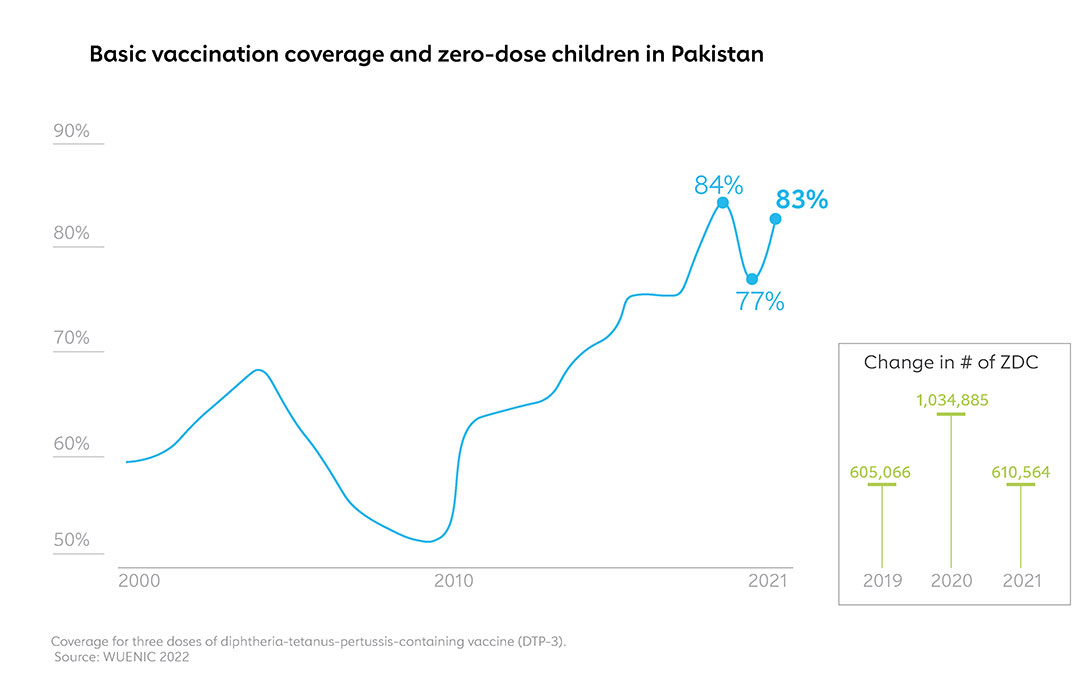

But by year’s end, the number of zero-dose children in Pakistan still stood at more than one million – a massive increase against 2019’s 600,000. Coverage with DTP3 – the third dose of the diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis vaccine, which acts as a conventional indicator for vaccination coverage in general – had dipped to 77% in 2020, down from 84% the year before.

“Our biggest fear was to start seeing a massive increase of outbreaks for measles, diphtheria or pertussis, particularly amongst the most vulnerable populations,” Jimenez says. “We felt it was becoming a time-bomb. However, despite the coverage backslide compared to previous years, it didn’t happen.”

“I still feel the most important thing to take care of is routine immunisation. It is the foundation and it is important that the foundation is strong.”

Lockdowns and social distancing measures likely helped smother smouldering fires, says Jimenez. But a vaccination bounce-back was critical. The latest data tell a story of Pakistan’s health system resilience: at end 2021, DTP3 coverage stood at 83%, against 2020’s 77% and 2019’s 84%, and the pandemic tide of zero-dose children had ebbed to near-2019 levels, with the country’s cohort of the unreached tallying 610,564.

Though the story by no means ends there – waves of the pandemic have continued to surge and break, challenging health systems again – the 2021 achievement places Pakistan in a slender minority. In what WHO and UNICEF are calling “the largest continued backslide in vaccinations in three decades,” country-by-country immunisation statistics released by the two organisations show that most countries’ children remain worse-protected against vaccine-preventable diseases at end-2021 than they were pre-pandemic. Globally, DTP3 coverage has dropped five percentage points to 81% since 2019.

So what went right in Pakistan? VaccinesWork reached out to public health leaders and Gavi experts for their thoughts.

Prioritising routine vaccines

Pakistan is massive, populous, and no stranger to epidemics - and its public health leadership knows it’s a good idea to make routine immunisation a priority. We spoke to Pakistan’s federal Health Minister Abdul Qadir Patel in his office in Ministers’ Enclave, Islamabad, late one recent evening. “I still feel the most important thing to take care of is routine immunisation. It is the foundation and it is important that the foundation is strong,” he said. “This is taken seriously by the entire Pakistan.”

Still, in Pakistan as in most countries, the COVID-19 vaccine campaign was in competition with routine childhood immunisation. Dr Faisal Sultan considers “engaging dedicated technical HR for the COVID response at all tiers” to be one of the most important strategies adopted to mitigate the impact of pandemic on the roll-out of other vital jabs.

“These are not accidental trends. It reflects diligence, commitment and capability of the entire chain, from top to bottom and in all directions around.”

In practice, protecting the resources required for routine immunisation meant lots and lots of hands on deck. In Sindh alone, says provincial EPI manager Dr Irshad Memon, “fifty thousand of our workers were in the field in one day, for fourteen days” when an adult COVID vaccination campaign coincided with routine immunisation activities. Besides the skilled health personnel, there were logistics persons, vehicles, stock-checkers, he says, “all working for COVID specifically. Not a single EPI vaccinator was involved in this entire workforce. Because a policy was adopted in our Ministry from the beginning – not to disturb routine services.”

Have you read?

Eagle-eyed opportunism

Making up the vaccination shortfall also relied on some canny manoeuvring, according to Dr Soofia Yunus, Director General of the Federal Directorate of Immunization (previously called the Federal EPI). “We grabbed every opportunity. Whatever opportunity we got with available financial and human resources, we piggybacked on it to give different options to the community.” When lockdowns were lifted, extended outreach activities for routine immunisation were bolted onto COVID immunisation sessions, she says, and tagged along with polio campaigns.

“I will say that Pakistan was very creative,” remarks Jimenez. “They really reacted by building new solutions.” In major cities, he says, integrated COVID-19 response efforts packaged vaccines and essential nutrition, deworming and other health interventions. In urban slums, Pakistan and its international partners – including UNICEF, WHO and Gavi – worked on enabling extraordinary evening and weekend shifts at immunisation outposts.

Flexible partnerships

That creativity hinged in part on the flexibility of Pakistan’s partners. “It was a collaborative effort,” says Dr Yunus. “One thing that helped us during this drive was the freedom to utilise the available grants to meet emerging needs – that flexibility allowed us to prioritise some COVID-related activities without compromising on the EPI services.”

Resources from all donors and partners were “pooled and streamlined” according to Dr Faisal. For Gavi’s part, says Jimenez, that meant pivoting on a dime to support everything from the procurement of masks, gloves and sanitisers, to the provision of out-of-hours health services. “We are extremely thankful to Gavi for helping us fulfil a major chunk of our responsibilities,” says Minister Patel.

Solid foundations, resilient health systems

Needless to say, the country’s response to the pandemic built on investments made over decades. The technological underpinnings of the system offer a case in point. Since 2017, Gavi has invested more than US$ 23 million in Pakistan’s cold chain and supply chain management systems. The pandemic, says Dr Yunus, has been a kind of stress-test. The result? The system passes – the infrastructure development programme has been “sufficient”.

Referring to the clubbed-together COVID-19 and routine outreach activities, Yunus says, “You can imagine the kind of vaccine movement that was going on at the district level. But we never heard from any areas that we don’t have cold chain, so we cannot have integrated campaigns.”

© UNICEF/UN0493478/Malik

Credit: Gavi/2020/Asad Zaidi

Dr Sultan believes that the pandemic has shown that “Pakistan can” – even faced with a dual or triple challenge. As routine immunisation bounced back during 2021, polio infection numbers headed into a period of retreat, and COVID-19 vaccination rates ramped up impressively. “These are not accidental trends,” he added. “It reflects diligence, commitment and capability of the entire chain, from top to bottom and in all directions around.”

Ownership at the grassroots and the frontlines

“I think the dedication of the frontline workers must be kept on the foremost.”

In other words, leadership and commitment from on high will get you only so far. “Until you get the local population involved and encourage their participation, you won’t achieve success,” explains Minister Patel. “Wherever we have achieved success, it has been because of this formula, and Insha’Allah, we would like to strengthen this programme even further.” Drumming up grassroots awareness of the population’s responsibilities is crucial, he adds.

Jimenez echoes him: “Considering the recognised presence of childhood diseases in the country, mothers are highly aware of the importance of vaccination to protect their children. And therefore, once the lockdowns were over, there was an interest from their side. It was a multi-stakeholder approach. There were new ways of getting the vaccines out there, but there was also sufficient demand to facilitate that.”

Dr Yunus recalls receiving calls from the provinces after the lockdowns, which made it clear that “the community wants immunisation services to be there – so after the initial lockdown, we never closed our EPI services”.

That required extraordinary commitment from the front line. Even as vaccinators risked falling ill with COVID-19, even as they lost friends and family members to the pandemic virus, Dr Yunus said, the provincial health care staff kept the routine immunisation programme running. “I think the dedication of the frontline workers must be kept on the foremost.”

More from Huma Khawar

Recommended for you