How falling vaccination rates are fuelling the antibiotic resistance crisis

Measles is a viral infection, so antibiotics don’t treat it directly. But it weakens the immune system, leading to bacterial infections like pneumonia or ear infections, which do require antibiotics.

- 29 July 2025

- 4 min read

- by The Conversation

Antibiotic resistance is one of the biggest health threats we face today. It’s often blamed on the overuse of antibiotics, and for a good reason. But there’s another major factor quietly driving this crisis that doesn’t get as much attention: low vaccination rates.

In early 2025, Ontario had a measles outbreak with 2,200 cases as of mid-July, mostly in people who hadn’t been fully vaccinated. An outbreak in Alberta that began in March has expanded to more than 1,300 cases as of mid-July.

Measles had been eliminated in Canada since 1998, but it’s now reappearing, largely due to missed or delayed vaccinations. On the surface, these might seem like a limited viral outbreak. But the ripple effects go much further, causing more illness, more complications and, ultimately, more antibiotic use.

Why measles can lead to antibiotic use

Measles itself is a viral infection, so antibiotics don’t treat it directly. But the virus weakens the immune system, leaving people vulnerable to bacterial infections like pneumonia or ear infections, conditions that do require antibiotics.

Unsurprisingly, this pattern isn’t new. A 2019 study published in Pediatrics showed that many children hospitalized with measles in the United States developed secondary infections that required antibiotic treatment, especially pneumonia and ear infections.

In early 2025, Ontario had a measles outbreak with 2,200 cases as of mid-July, mostly in people who hadn’t been fully vaccinated.

While data from the Ontario outbreak is still being analyzed, experts expect a similar surge in antibiotic prescriptions to treat these preventable complications.

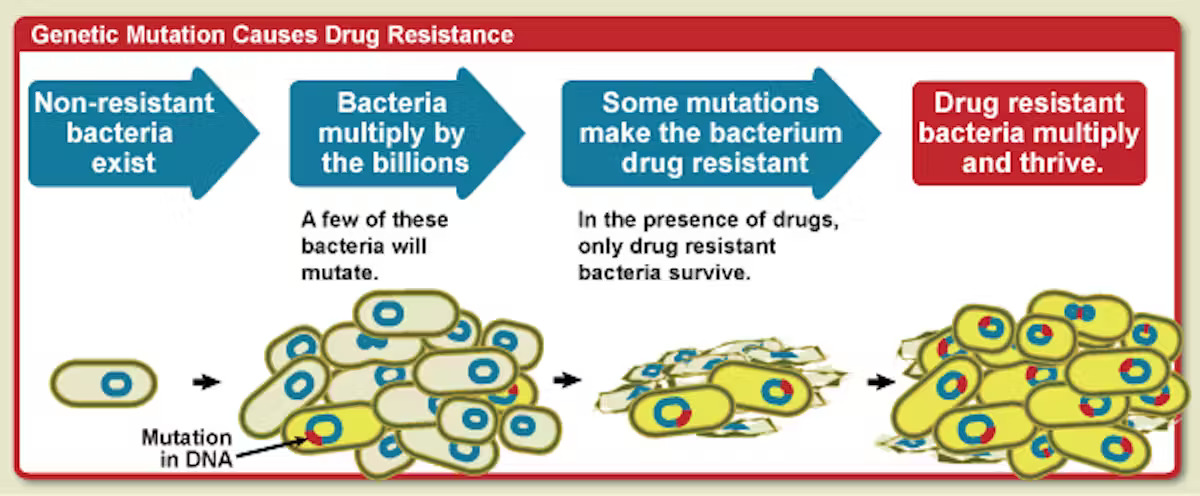

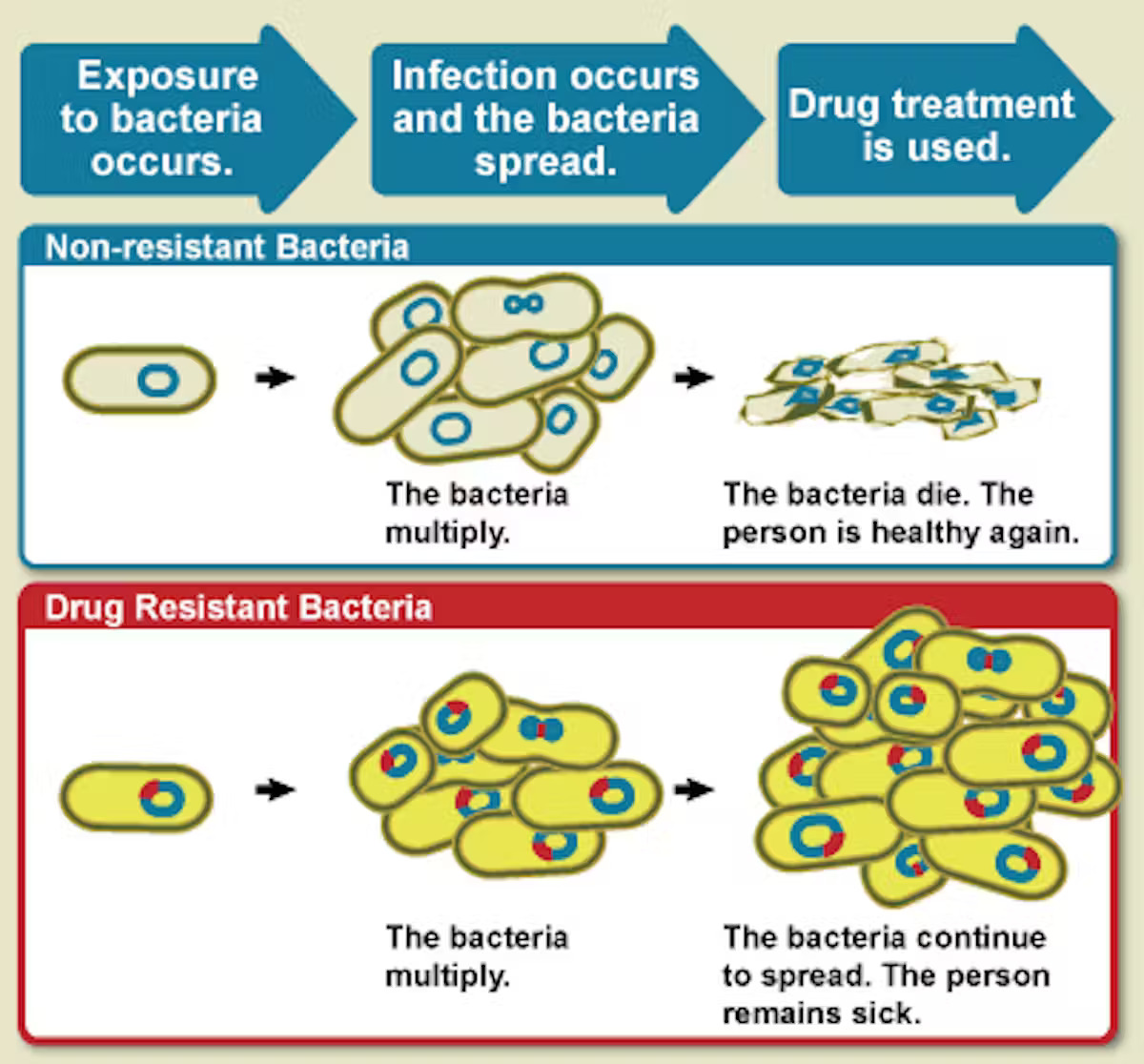

The antibiotic resistance chain reaction

Here’s where it gets dangerous. Every time we use antibiotics, we give bacteria a chance to adapt. The most vulnerable bacteria die, but tougher ones survive and spread. This leads to antibiotic resistance where treatments that used to work no longer do.

Even appropriate use of antibiotics, like treating a bacterial infection after measles, adds to the problem. And the more often we need to prescribe antibiotics, the faster this resistance builds.

Have you read?

A 2022 global study published in The Lancet estimated that antimicrobial resistance directly caused 1.27 million deaths in 2019 and contributed to many millions more. As resistance spreads, doctors are forced to use more toxic, expensive or last-resort drugs, and sometimes, no effective treatment exists at all.

How vaccines help fight resistance

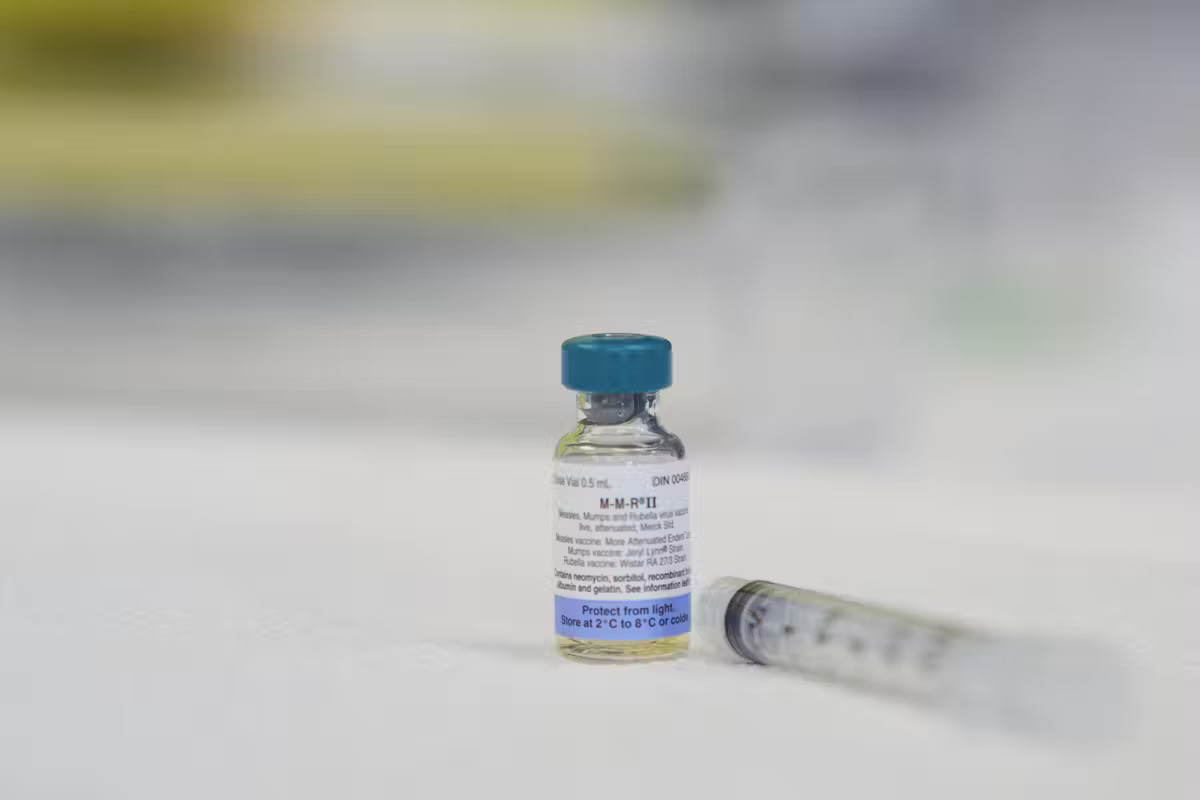

Vaccines are one of the most powerful tools we have not just to prevent disease, but to reduce antibiotic use and slow resistance. By stopping infections before they happen, vaccines reduce the need for antibiotics in the first place.

Some vaccines protect directly against bacteria. Pneumococcal vaccines (PCV13, PCV15, PCV20) guard against a major cause of pneumonia, brain infections and ear infections. Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) and diphtheria vaccines prevent other respiratory bacterial diseases.

Other vaccines protect against viruses, which can weaken the body and open the door to bacterial infections called as secondary bacterial infections.

The MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) vaccine not only prevents measles but also reduces the chance of bacterial pneumonias that often occur after measles due to immunosuppression.

The seasonal flu and COVID-19 vaccines help prevent viral infections that can trigger secondary bacterial complications.

The rotavirus vaccine that protects against diarrheal disease in children has also been shown to reduce antibiotic use by more than 20 per cent, according to a 2024 study in Vaccine.

In fact, a 2020 study in Nature found that improving childhood vaccination coverage in low- and middle-income countries could reduce antibiotic-treated illnesses in kids under five by more than 20 per cent. That’s a massive step forward in the fight against antibiotic resistance.

A wake-up call

The measles outbreaks in Ontario and Alberta aren’t just local issues; they are a global warning. Each missed vaccine doesn’t just put one person at risk; it potentially means more infections, more complications and more antibiotics. That, in turn, means more antibiotic resistance for everyone.

Vaccines are not just about individual protection. They are a public health strategy that keeps antibiotics effective for when we really need them, especially for vulnerable people like cancer patients, transplant recipients and the elderly, who rely on antibiotics to survive routine infections.

Vaccines, in fact, do more than prevent disease. They protect our ability to treat infections by reducing the need for antibiotics and slowing the rise of resistant bacteria. With preventable diseases like measles making a comeback, now is the time to recognize the broader impact of vaccine hesitancy.

Choosing to vaccinate is more than a personal decision. It’s a way to protect our communities and preserve the life-saving power of antibiotics for generations to come.