New data shows “staggering” increase in measles deaths worldwide

Some 136,000 people died of measles in 2022, a 43% increase on 2021, amid a protracted slump in immunisation rates.

- 16 November 2023

- 6 min read

- by Gavi Staff

Measles killed an alarming 43% more people worldwide in 2022 than in 2021, according to data released today by the USA's Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO).

Some 136,000 people, most of them children, died of the highly contagious but vaccine-preventable viral infection last year.

Two doses of the vaccine are 97% effective at offering protection for life – a fact that underlies another striking statistic: measles mortality has dropped by 82% since 2000, when an estimated 772,854 were estimated to have died in a year.

The spread and scale of global measles disease incidence also rose, with 18% more infections – totalling more than 9.2 million cases – recorded worldwide in 2022. Thirty-seven countries, up from 22 countries in 2021, recorded "large and disruptive" outbreaks of measles.

"Staggering" – but also anticipated

The new figures quantify a disaster that experts have been warning of since COVID-19 crash-landed into health systems around the globe, causing vaccination coverage to crater in virtually every country. In a statement, the CDC's John Vertefeuille, director of the organisation's Global Immunization Division, called the increase in measles outbreaks "staggering, but unfortunately, not unexpected".

Airborne and efficient, measles is one of the most contagious human viruses known to science, which means it's uniquely adept at exploiting even the slenderest gaps in a population's immunity. "From a disease-control point of view, we say, you know, measles will find communities that have low vaccination coverage, or susceptible persons," disease control expert Dr Peter Strebel told VaccinesWorklast year.

Though the vaccination coverage gaps left behind by the pandemic's brutal early impact have narrowed, the holes in the global measles safety net have remained dangerously large.

WHO considers populations with a 95% immunisation coverage rate safe from measles; the world currently hovers at an alarming 83%. Thirty-three million children missed at least one of two necessary doses of measles vaccination in 2022. Twenty-two million of them didn't receive even their first.

Inequitably sick

While the new data does not break down measles mortality by country, it does estimate that 63% of the year's measles deaths occurred in Africa, 29% in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean region and 7% in the WHO South-East Asia region.

We also know that half of the children who received no measles vaccine at all in 2022 lived in just ten countries, and six of those – the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, India, Madagascar, Nigeria and Pakistan – are classed as lower-income countries.

Inequitable gaps in measles protection only magnify the virus's in-built appetite for poverty. While in Western Europe, measles infection is fatal in about 1 in 5,000 cases, in the poorest parts of the world, more than 1 in 100 children who contract the disease may die.

That's because, even within a single town, worse nutrition and crowded living make measles a deadlier disease amid lack than plenty. If a poor child's body is primed to be more vulnerable to the virus's attack on the immune system, that child is also less likely to be caught by the health system when he or she falls ill. "Measles is called the inequity virus for good reason," said Kate O'Brien, WHO's Director for Immunization, Vaccine and Biologicals, reflecting on the new figures in a statement.

"Unfortunately more cases does mean more deaths – but it's important to understand where these cases occur as case fatality ratios (CFR) will be higher in areas where there is inaccessibility to adequate health services, including fragile and conflict areas where malnutrition may be more prevalent, as well as other secondary infections," says epidemiologist Dr Stephen Sosler, Gavi's Head of Vaccine Programmes.

What Gavi’s doing to help:

Between 2000 and 2022, Gavi helped countries reach approximately a billion children with routine vaccines, including measles vaccine.

In 2023, Gavi has:

- Disbursed more than US$ 12 million to support measles outbreak response in six lower-income countries;

- Supported health systems' efforts to plan, fund, and roll out measles-rubella "follow-up campaigns" – which include children aged from nine months to five years – in nine lower-income countries so far in 2023…

- …with three more campaigns to come before year's end.

In 2024, Gavi will support at least 15 lower-income countries – those disproportionately at risk of major outbreaks, according to this latest data – to conduct preventive measles and rubella vaccination campaigns, to protect an estimated 38.5 million children.

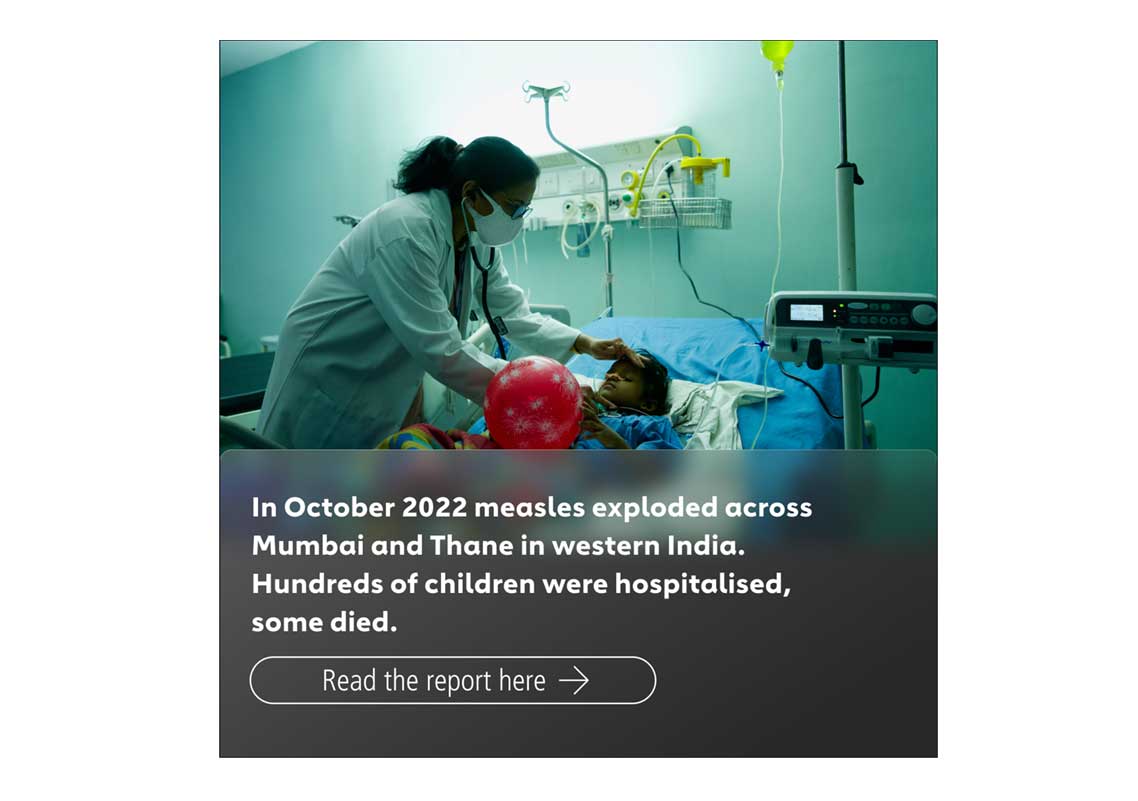

One in 136,000

"The main problem was unimmunisation," Dr Vandana Kumavat, Head of Paediatrics at a Rajiv Ghandi Medical College Hospital in Thane, a city in western India, told VaccinesWork earlier this year, reflecting on the outbreak she watched fill up her wards in late 2022 and early 2023.

Have you read?

Her department admitted and cared for 177 critically ill measles patients in an emergency isolation ICU in the months of that crisis. Beyond a lack of immunisation – 150 of the 177 were confirmed to have missed even their first dose of measles vaccine – the children she saw also followed a socio-economic pattern: the majority of them came from poorer, Muslim-majority enclaves of the city.

On 23 November 2022, Arhad Khan, almost two years old and unvaccinated, was admitted to Dr Kumavat's measles ICU. Measles had tanked his immune system: opportunistic infections had set in. On November 27, he died with measles-linked bronchopneumonia, septicaemia and Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. He was one of two recorded measles deaths in Thane in 2022 , and, as we now know, one among some 136,000 worldwide.

But equitable vaccination can level the inequitable risk posed by the virus. In Kenya's conflict-troubled Mandera County, which has some of the country's lowest immunisation rates, VaccinesWork spoke to Deka Dacar, who had lost two children to measles, and was campaigning for increased vaccine uptake amid an outbreak in late 2022. "I will not allow another mother to lose her children when we have vaccines," she said.

Two doses of the vaccine are 97% effective at offering protection for life – a fact that underlies another striking statistic: measles mortality has dropped by 82% since 2000, when an estimated 772,854 were estimated to have died in a year.

After measles

What's next? Unfortunately, measles has a well-earned reputation as an epidemiological harbinger as well as a threat in its own right. Because it's so infectious, measles tends to be the first pathogen to exploit a breach in a population's immune defences, but it's often not the last.

"We're already seeing this with outbreaks of diphtheria and type 1 circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus," said Sosler. "Both of these are rare and only occur when routine immunisation (RI) coverage levels are persistently low."

The solution, he says, is to raise immunisation levels across the board – strengthening routine immunisation, timeliness and quality of preventive campaigns and mounting "Big Catch-Up" campaigns to push back against what he calls the lingering "Long COVID" effects on health systems.