New vaccines make big impact in rural Uzbekistan

Pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines are not only shielding children from disease, they’re building confidence in vaccination in the country’s remotest corners.

- 20 February 2026

- 6 min read

- by Umida Maniyazova

At a glance

- Ten years ago, the Ministry of Health of Uzbekistan, in partnership with Gavi, rolled out two new vaccines that protected against diarrhoea-causing rotavirus, and meningitis- and pneumonia-causing pneumococcus. The two infections were causing thousands of paediatric hospitalisations and many hundreds of deaths each year.

- Health workers say the impact has been dramatic. “Almost every week, we saw severe infections before. Now it’s rare,” said a health worker from rural Qo’rg’ontepa.

- The vaccines’ evident effectiveness is reinforcing parental confidence in vaccination. “I believe that vaccines against rotavirus and pneumococcus are especially important because, if a child contracts these diseases, vaccination helps them experience the illness more mildly and safely,” one Qo’rg’ontepa mother said.

About a decade ago, respiratory infections and diarrhoeal diseases were among the leading causes of paediatric hospitalisation and death in the rural villages scattered across Uzbekistan’s endless plains.

Pneumococcal disease, caused by the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae, often led to severe pneumonia, meningitis and bloodstream infections. Rotavirus was estimated to cause about 5,491 hospitalisations and 662 deaths each year among children under five years of age in 2005–2009.

But the introduction of two vaccines, the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) and the rotavirus vaccine, have altered that picture significantly.

Rolling out change

The Ministry of Health of Uzbekistan, in partnership with Gavi, introduced the rotavirus vaccine in 2014 and the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) in November 2015.

Research conducted in Uzbekistan before the vaccine’s introduction confirmed the heavy burden of both these infections. Between 2008 and 2013, for instance, recorded cases of pneumococcal meningitis in children tended to present in advanced and highly dangerous forms: 83.3% of young patients presented with a severe form of the disease, one in three (36.3%) developed convulsive syndrome, and 72.2% faced life-threatening complications such as cerebral oedema and toxic shock syndrome.

Pneumococcal pneumonia also frequently led to serious consequences, with 73% of children experiencing complicated forms, including lung damage and inflammation of the lining of the lung.

Dr Renat Latipov, a WHO specialist in Uzbekistan, estimates that rotavirus was also responsible for at least 32,000 visits to primary healthcare providers and over 330,000 cases of diarrhoea treated at home each year.

The scale of the threat posed by pneumococcus is confirmed by microbiological monitoring data from the same period: Streptococcus pneumoniae was isolated in nearly half (46.6%) of hospitalised children with purulent meningitis and in 13.9% of patients with pneumonia.

Of particular concern was the spread of strains resistant to widely used antibiotics, such as erythromycin (36.2%) and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (53.3%), which made treatment particularly challenging.

The new vaccines gained ground quickly, with immunisation coverage for rotavirus increasing from 52% in 2014 to between 90% and 99% in the 2017–2024 period. Coverage with all three doses of PCV stabilised at 98–99% in the 2021 to 2023 period, with a dip to 94% in 2024.

The impact was felt rapidly. “Before vaccination, rural medical offices registered an average of 20 diarrhoea cases per week; after vaccination, this figure dropped to just five cases per week,” Dr Latipov said.

Indeed, scientific studies had found similar impact. Research on the effectiveness of the rotavirus vaccine in Bukhara and Tashkent in 2015–2016 showed that it reduces the risk of a child’s hospitalisation for rotavirus infection by 51%, and its effectiveness reached 67% against the most severe cases requiring prolonged treatment.

Regarding the pneumococcal vaccine, within just two years of its introduction, by 2016, the number of pneumonia cases in children under five had decreased by 54% compared to the pre-vaccination period, and the rate of confirmed pneumococcal meningitis in hospitals in Tashkent and Samarkand decreased by 2.6 times.

In rural villages, confidence in vaccination grows

The shift was perhaps most dramatic in the country’s remotest places, where timely access to curative care can be a challenge, but where the vaccination system still tends still to achieve high levels of coverage.

In Qo’rg’ontepa village in Andijan province, nestled amid Uzbekistan’s picturesque foothills, for instance, vaccination campaigns have dramatically reduced hospital admissions for pneumonia and acute diarrhoeal diseases in children.

“Almost every week, we saw severe infections before. Now it’s rare,” said local health worker Shaira, who has administered the vaccine to hundreds of children.

She says parents are more confident seeking out the vaccine than they used to be: “Before, we had to go door to door in rural homes, pleading with parents of young children to come for vaccination. Now, mothers bring their kids to rural health posts themselves, asking when the next dose is due.”

She sees this as a victory of strong information campaigns by rural medics – and proof that families have witnessed the vaccines’ effectiveness and their children’s improved health.

Have you read?

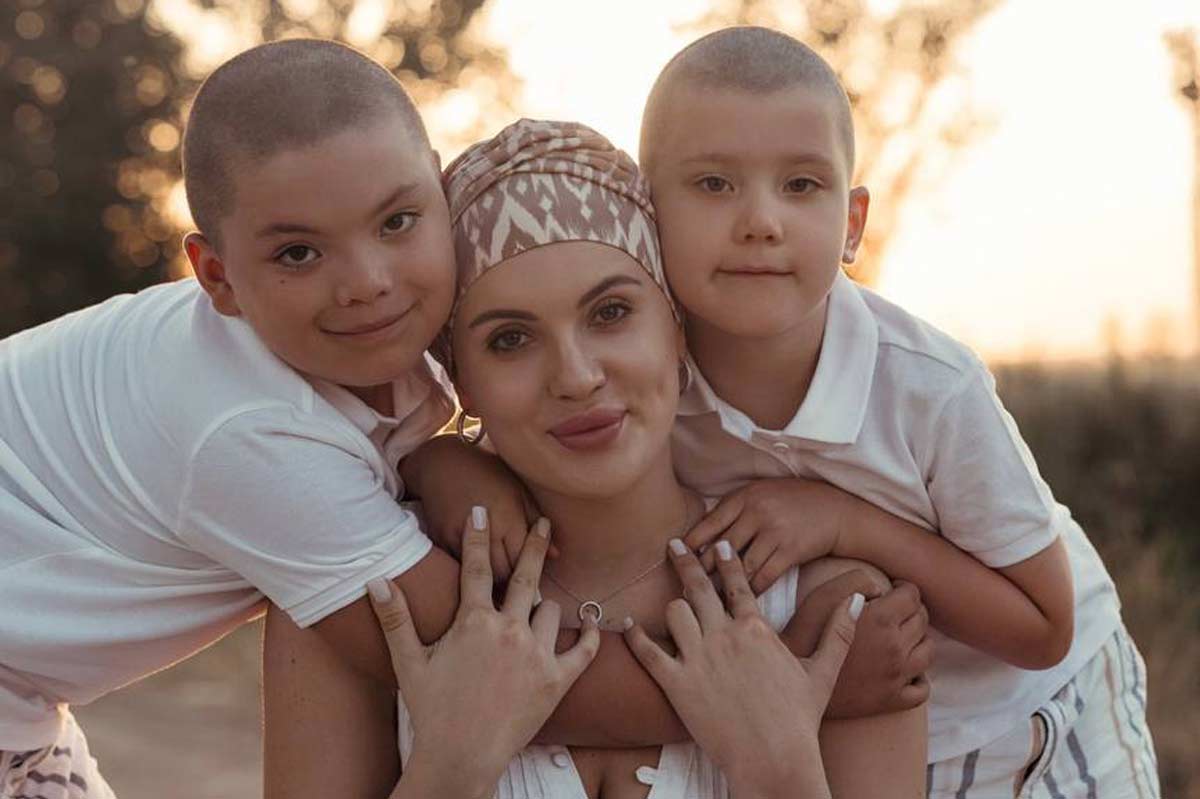

Mokhinur Sotvoldieva, 28, a resident of Qo’rg’ontepa village in Andijan province and a mother of two, explains: “I believe that vaccines against rotavirus and pneumococcus are especially important because, if a child contracts these diseases, vaccination helps them experience the illness more mildly and safely. Naturally, minor side-effects may occur with any vaccine, but the risk is far lower than the risk posed by the diseases themselves. That’s why I prioritise timely vaccination for my children. After receiving rotavirus and pneumococcal vaccines, I’ve become much more willing to travel with my kids without fear, as it has given me confidence in their protection from many serious illnesses. In this way, not only are they protected, but those around them are as well,” says Mokhinur.

Her five-year-old daughter had some discomfort after the pneumococcal shot, while her two-year-old son showed almost no reaction. “Each child responds differently, so vaccinations should follow a thorough medical check-up, doctor’s recommendation, and parental consent,” Mokhinur said.

Expanding further

As noted by the Ministry of Health, to further expand vaccination coverage in the rural areas of Uzbekistan demands strengthening primary healthcare facilities, deploying outreach teams, and reinforcing cold chain and logistics systems so that core childhood vaccines are reliably available at village level.

These include all the vaccines given free of charge per the National Immunization Schedule, including the oral polio vaccine (OPV), inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), rotavirus vaccine, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV), Hib-containing combination vaccines and others.

Health authorities underline that, both in urban centres and in rural communities, these vaccines are now consistently in stock at public clinics, enabling parents across the country to complete their children’s full vaccination schedule on time.