From theatre to TikTok: how a Kenyan youth group is tackling malaria

The Kenya Malaria Youth Corps are bringing a Gen Z flavour to awareness campaigns against the mosquito-borne bug.

- 18 September 2025

- 6 min read

- by Muthoki Kithanze

A preacher makes his entrance, announcing to nobody in particular that the man lying on a bed before him, sick with malaria, is not to be taken to hospital, despite his relatives’ fervently expressed wishes. Instead, the patient is to wait for healing from ‘above’.

Nobody, not even the ill man’s parents, registers their disapproval. The preacher is a revered figure, and his word is accepted as final.

But the disease progresses despite the preacher’s edict. The man’s bodily functions shut down slowly, and then with frightening speed, until he breathes his last breath.

At his funeral, a health worker known to the family stands to speak. “We have lost our brother today, but we do not have to lose others from a disease that can be. Let us take our loved ones for treatment and children for vaccination.”

Neither the funeral nor death were real. But many in the crowd would agree that the sketch, staged by members of the Kenya Malaria Youth Corps (KeMYC) in Kenya’s Naivasha town, was a true reflection of what happens in communities when religious belief prejudices medical care, exposing people unnecessarily to serious illness and even death.

“Performed art leaves a memorable impression on people. It is easier to recall events acted out in a play than it is to remember reading a book or a pamphlet with the same message,” KeMYC member Eliud Wanjala, 29, told VaccinesWork.

A social movement

Malaria remains a major public health problem in Kenya and accounts for an estimated 13–15% of all hospital consultations. Approximately 70% of the population is at risk, including 13 million people in endemic areas and another 19 million in highland epidemic-prone and seasonal transmission areas, according to data from the Kenya Malaria Indicator Survey, 2020.

Commissioned in 2021 by former president Uhuru Kenyatta under the auspices of African Leaders Malaria Alliance (ALMA), KeMYC is a youth group dedicated to championing malaria elimination through community engagement.

Since its establishment, the group has built a presence in eight regions across the country. “Our work is guided by the Kenya Malaria Strategy 2023–2027, which recognises the importance of community-led action and youth involvement,” says John Mwangi, country lead, KeMYC.

Have you read?

Typically, public health messaging follows a familiar pattern: posters slapped on the corridors of hospital walls and broadcast messages carried by health care workers moving through the neighbourhood.

But this group has charted its own course, Mwangi says. “Our youth creatives use videos, spoken word, music, infographics and trending social media challenges to drive engagement.”

That doesn’t mean KeMYC eschews traditional models altogether – they’ve been known to pull together roadshows, door-to-door campaigns, community dialogues and school programmes too, he says.

‘Zero malaria starts with me’

As Eliud Wanjala headed towards a Kakamega restaurant to meet with VaccinesWork, many people shouted greetings to him – he answered with loose promises to meet with them later. “I lead community mobilisation in this region, so it is common for people to know me,” he said with an embarrassed smile.

Kakamega is one of Kenya’s high-malaria burden areas, with a prevalence of 15.2%, more than double the national rate.

Wanjala, who runs a small business, joined KeMYC in 2023 after a friend told him about it. “I have a history of a loved one dying from the disease, which makes this undertaking personal,” he says.

Part of Wanjala’s mobilisation work is finding spaces where KeMYC’s message can be heard. Sometimes that means securing a stage for plays, such as during international days like Malaria Day or Youth Day. Other times it’s simply making sure their ground sensitisation efforts are shared on camera and have a chance to ripple out across the internet.

If you scroll through their TikTok page, which has so far garnered close to 7,000 likes, you discover a blend of creations. In some clips, group members are holding message placards; others quiz malaria know-how. In others, they speak directly to the camera, or dance alongside a guest to a song. Yet the message is never diluted in the fun. It is always clear and urgent: zero malaria starts with me.

Getting an online generation on-side

The group has forged alliances not just with the communities they seek to influence, but with the health workers who train them up, and Ministry of Health officials who join their podcasts and lend authority to their messages.

Jackline Vutita, a community health promoter from Lumino village in Kakamega, calls KeMYC’s popularity extraordinary. “In my 20 years of doing community work, the youth were hardly there: this work has always been done by women and countable men.” The perception was that health work was high-input, low-reward, she explains. Now she marvels at the improved numbers and commitment of the youth.

“Young people are trusted by the community despite their youthful nature, and they are able to mobilise community outreach programmes online consistently, something that I cannot do,” Vutita says.

Helping keep parents on the vaccine track

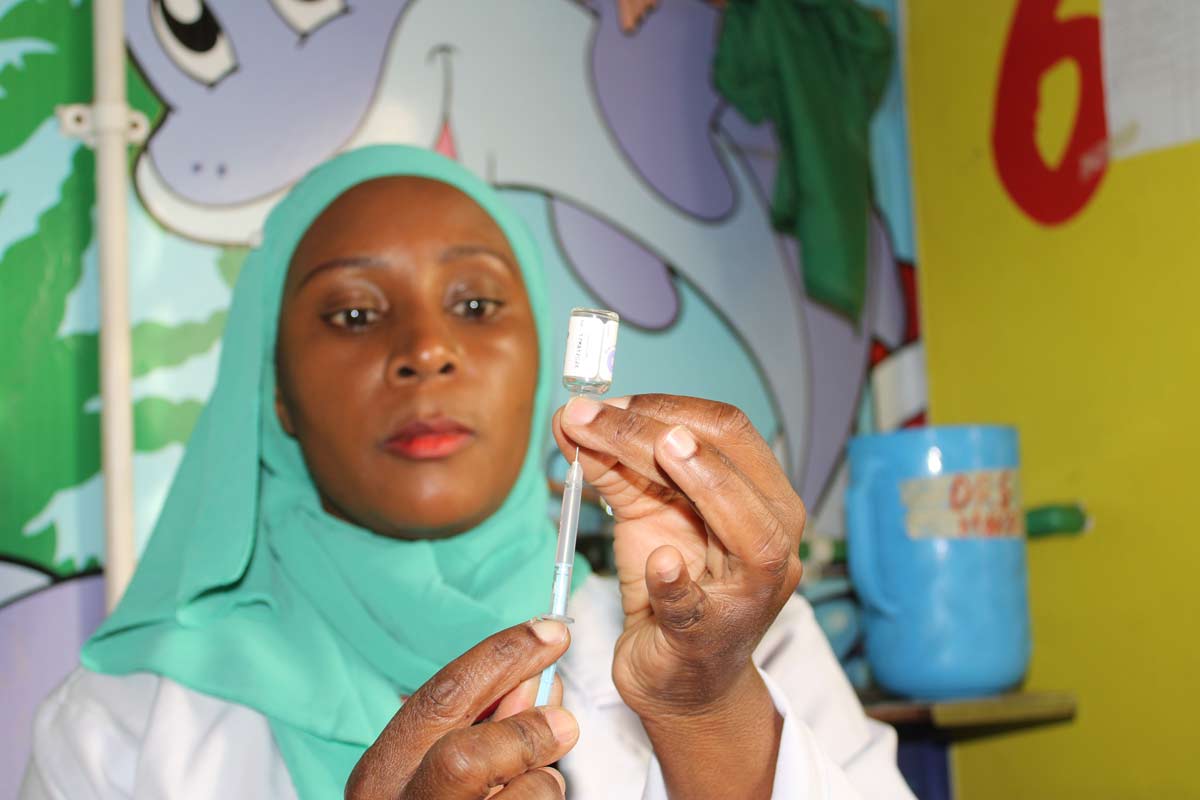

Mumias West Level 4 hospital, one of the busiest public hospitals in Kakamega, recorded 843 malaria cases of children under five in 2023. The number dropped significantly to 511 in 2024, says Agneta Aseko, a nurse at the Mother and Child department, who attributes the decline to an impressive malaria immunisation rate.

Despite the challenges inherent to delivering a vaccination course that comes in four doses, close to 400,000 children across the Lake Endemic counties were vaccinated between the programme’s start in 2019 and early 2023.

Vaccine sensitisation efforts by people like Miriam Akinyi, 29, may be helping more caregivers to adhere to the long vaccination schedule. Akinyi, a member of KeMYC from Nairobi county, hosts podcasts in which she regularly engages members of the community to share their testimonials, often telling stories of their children who have been fully vaccinated.

She explains that producing a podcast, starts with identifying a suitable guest. Recording sessions are usually conducted in health facilities or at locations convenient for both the guest and the production team.

Each session runs for about an hour, with Akinyi skilfully guiding the conversation. “We started podcasting last year to give every region a chance to handle particular issues that affect them – like vaccine hesitancy. So far, we have six episodes,” she says.

All the various efforts mounted by the group feed into the Zero Malaria Starts With Me campaign, a pan-African push to stamp out the disease.

“In the first quarter of this year alone, [our] group directly engaged over 1,000 adults across different counties. Social behaviour change is not something that happens instantly, but we hope that when the new Kenya Malaria Indicator Survey is released later this year it will reflect our efforts,” Akinyi said.

More from Muthoki Kithanze

Recommended for you