Will the new variant of COVID-19 make re-infection more likely?

New variants of the coronavirus are causing alarm across the UK and South Africa, with many countries closing their borders to travellers from these countries. But what effect could new strains have on our ability to control the pandemic?

- 18 January 2021

- 3 min read

- by Priya Joi

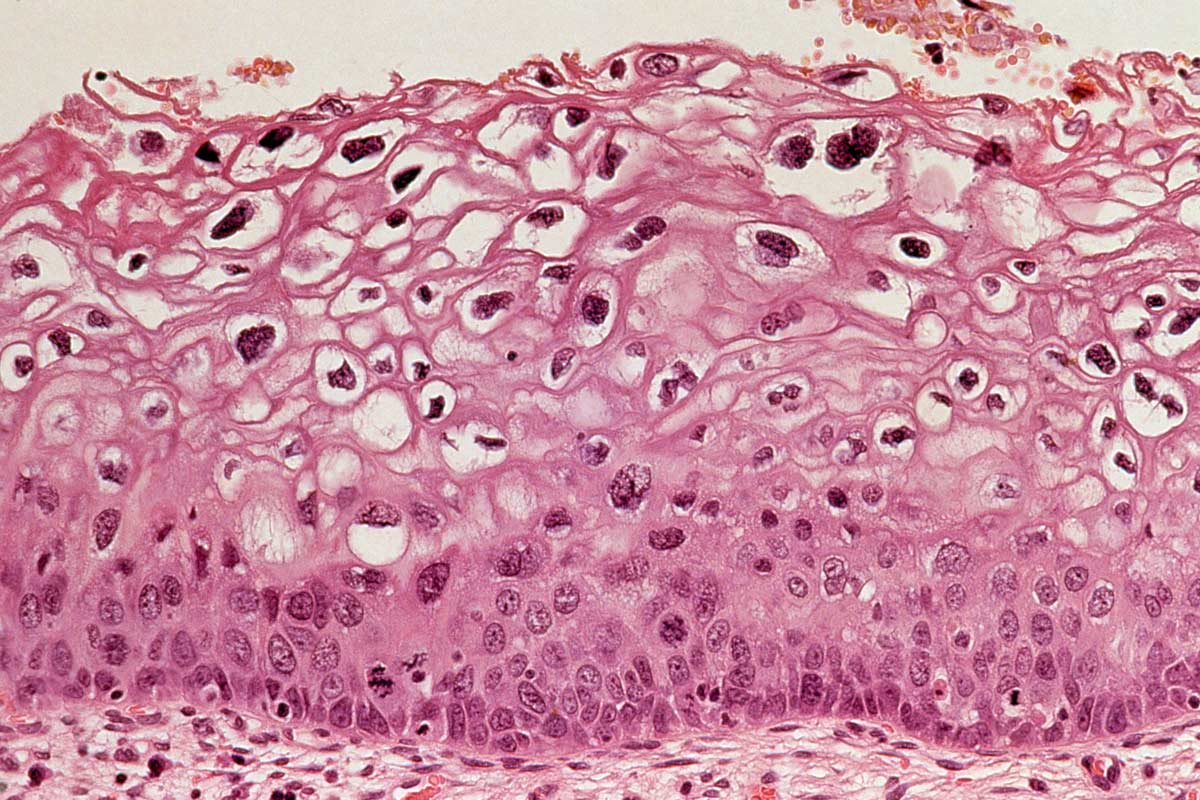

New variants of COVID-19 identified in late 2020 have now spread rapidly across the UK and South Africa, with a new one now emerging in Brazil. But, even though their increased infectivity and transmissibility means more people are dying, there is no evidence yet that they pose an increased risk severe disease or death to individuals. Now however, cases of reinfection are being detected that have been caused by the so-called N501Y variants.

Reinfection is still relatively rare, though it is generally only picked up when an individual experiences two separate infections that are both symptomatic.

What does this mean for the pandemic?

Reinfection in this situation means two or more infections by distinct strains of SARS-CoV-2. The first case of reinfection in the USA was in April 2020 in a 25-year-old man from Nevada. There have been other cases from Belgium, Ecuador and Hong Kong. None of the people were immune-deficient.

Reinfection is still relatively rare, though it is generally only picked up when an individual experiences two separate infections that are both symptomatic – which could mean people are being reinfected and are either asymptomatic or only experience mild disease that is not detected.

Improving our identification of reinfections is critical to understanding how well infection confers natural immunity that prevents reinfection – which will, in turn, be important to understanding how well vaccines will need to work in order to achieve herd immunity.

Have you read?

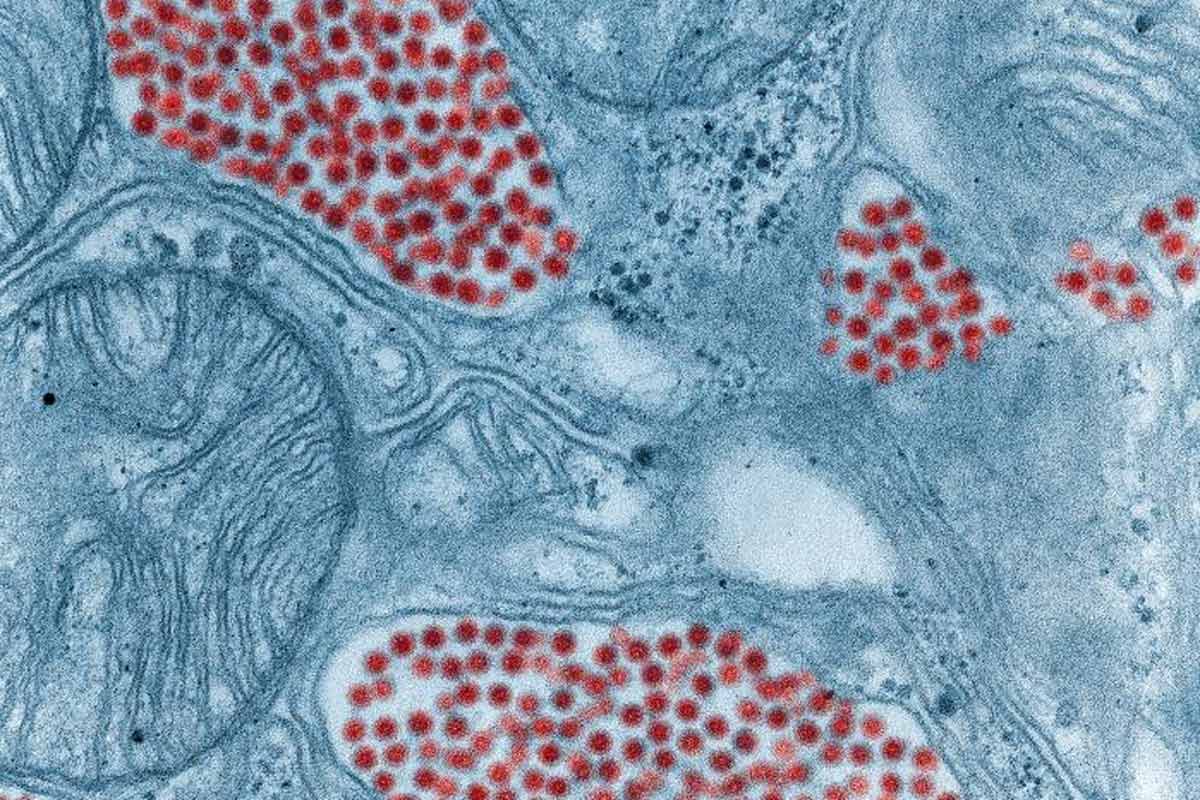

Could the new variant evade the vaccine?

In a case of reinfection in a 78-year-old man with the new UK N501Y variant (which is also called 202012/01), the second infection did cause more severe disease. However, there is no evidence that the increased severity the second time round was due to the variant being more pathogenic or because the individual had a weakened immune system due to other co-morbidities.

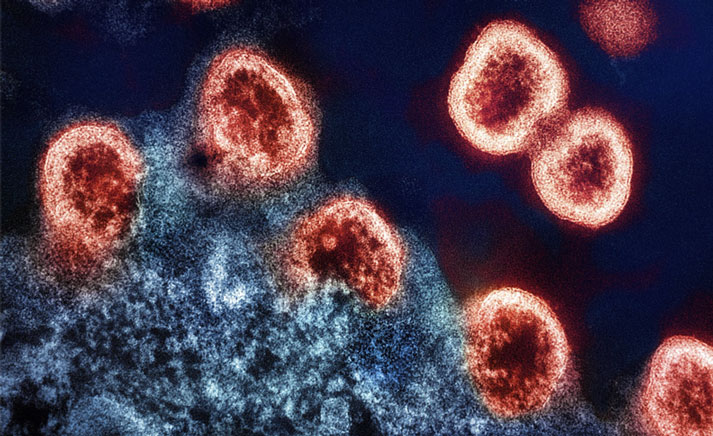

Researchers were initially concerned that he became infected with the new strain despite having antibodies from his previous infection – if this became a common occurrence it could potentially jeopardise the effectiveness of vaccines. The study did look into antibodies against the spike protein, which is the main component of most of the vaccines in development, so it’s still unclear if immunity to this protein can be escaped by the new strain.

Reassuringly, however, a recent laboratory study showed that serum from people vaccinated with the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine was equally effective at neutralising the virus strain that was used for the vaccine, as well as a modified virus carrying the N501Y variant, which is present in the newly circulating strain in the UK.

Because both vaccination against and natural infection with SARS-CoV-2 produce a response that targets several parts of the spike protein, scientists believe it is unlikely that the virus would accumulate the multiple mutations in the spike protein needed to evade immunity induced by vaccines or by natural infection.