Dr Saima Zubair: Pakistan’s loudest voice for HPV prevention

In conversation with HPV champions – an interview by Jhpiego.

- 19 November 2025

- 13 min read

- by Areej Javed

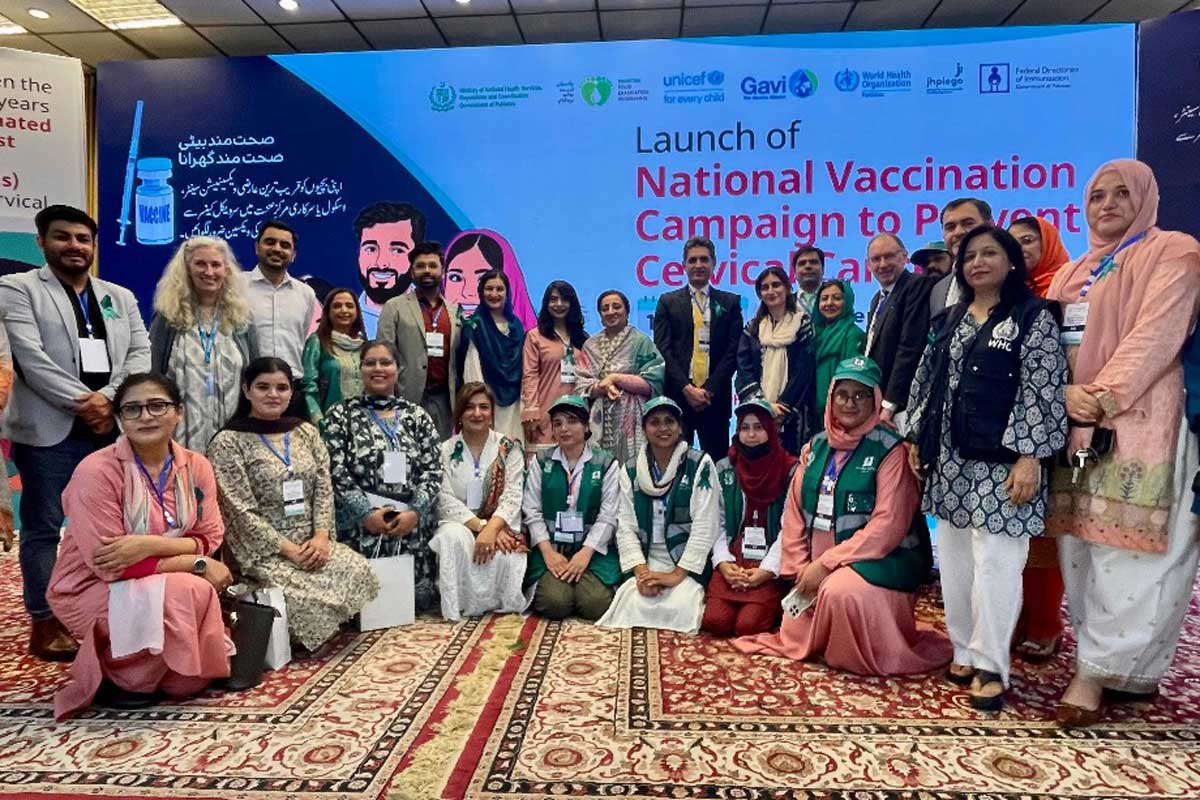

Pakistan has reached a defining moment in its fight against cervical cancer with the launch of its first-ever nationwide human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination campaign – a historic public health milestone protecting nearly 13 million girls aged 9–14 years across Punjab, Sindh, Islamabad Capital Territory and Azad Jammu & Kashmir.

Led by the Ministry of National Health Services Regulations and Coordination and the Federal Directorate of Immunization, with support from Jhpiego, WHO, UNICEF Pakistan, Gavi and provincial EPI teams, this effort has also benefitted from the dedication of individual HPV champions.

One of them is Dr Saima Zubair, an obstetrician-gynaecologist whose passion and perseverance have made her one of Pakistan’s most influential voices for HPV prevention. From engaging parents and teachers to countering misinformation and creating educational content in 12 regional languages, Dr Zubair has become a trusted advocate and bridge between science and society.

Children today are different: they are informed and opinionated. Talk to them honestly and clearly.

In an in-depth conversation last week, Dr Zubair took us through her work as part of the national campaign to end cervical cancer. That conversation, edited for length and clarity, follows below.

Dra Saima, thank you for speaking with us. To begin, what first inspired you to become a doctor?

Dr Saima Zubair: I was in class five when we lost our baby cousin after delivery. I was the eldest cousin at that time, and the feeling of helplessness in the family stayed with me. That was the moment I decided that I would become a doctor. Initially I hadn’t thought of becoming an OB-GYN; I was more interested in cardiology. But things change, and life takes you to where you can make the most difference.

How did you find your way into gynecology specifically?

Dr Saima: It happened during my third year of MBBS at Bolan Medical College, Quetta. I remember my very first day in the OBGYN department. The labour ward was full, there were more mothers than healthcare providers. At one point a provider was juggling two patients in delivery and a doctor screamed that somebody help her! But there was no free healthcare provider to help. That’s when I jumped in with my bare hands. I assisted the delivery and saw closely how everything, a young new life, hangs on skilled hands and quick help. That moment changed me. I realised how sacred and essential this work is, and it motivated me to pursue obstetrics and gynaecology. I take pride in the fact that I serve mothers; mothers with Jannah (heaven) under their feet.

Your career moved from clinical work toward public health. What drove that shift?

Dr Saima: If we rely only on curative strategies, we will always be playing catch-up. We need to move toward preventive strategies and policies. That’s why I did my public health master’s in maternal, child and adolescent health. I wanted to do impactful work where you can set short-, medium-, and long-term goals and see the results. That’s what motivates me: seeing measurable impact.

When did cervical cancer and the HPV vaccine enter your professional life?

Dr Saima: I was very lucky to be trained by Professor Ghazala Mahmud, a legendary professor and one of the few doctors in gynaecologic oncology in Pakistan. She is a master; her fingers did what I used to call a classical dance during surgery. Under her, we had gynaecologic oncology patients coming into PIMS, and I saw all kinds of cervical cancer patients. At that initial time, when the HPV vaccine first appeared in the private sector, we were among the first to use it. Many gynaecologists took it for their daughters. But it was very expensive and didn’t expand across Pakistan. So, my link with the HPV vaccine goes back 10–15 years.

What influenced your perspective on vaccines and prevention?

Dr Saima: COVID-19 changed everything for me. I lost my beautiful mother during it. Before she passed, we were both very involved in helping other healthcare providers with PPE, making and sending supplies across Pakistan. My mother used to sit with me; we would design and make PPE ourselves because the available styles didn’t fit female workers well. Females had issues with that style, so we designed a new style of PPE that was more suitable. When I lost my mother, it made me see, very personally, that prevention and vaccines, save lives. That bond with vaccines became very real and strengthened my commitment to vaccine advocacy.

Can you describe the current burden of cervical cancer in Pakistan as you see it?

Dr Saima: It’s alarming. We’ve all seen the figures: 5,008 cases for 2022–2023 and 3,197 deaths in the same period. Cervical cancer used to be fourth or fifth in ranking; now it’s rising to the second most common cancer among women of reproductive age. Pakistan has a very young population – about 68% are under 30 – and that’s exactly the time when exposure to HPV can become persistent. We see the first peak of disease by the late 30s and early 40s, but the infection mostly happens years earlier. To save these women we must do two things: vaccination and screening.

How effective has screening been in your experience, and what are the barriers?

Dr Saima: We used to do screening using visual inspection with acetic acid; we had a colposcope and performed punch biopsies and detected precancerous lesions at PIMS. But that opportunity served very few women.

Internationally, with functional insurance systems, you make appointments and there’s a pathway to follow. In Pakistan, our services are readily available in some places but we lack health education. I feel health education should be the number one priority for our country and be a part of education system as a regular subject.

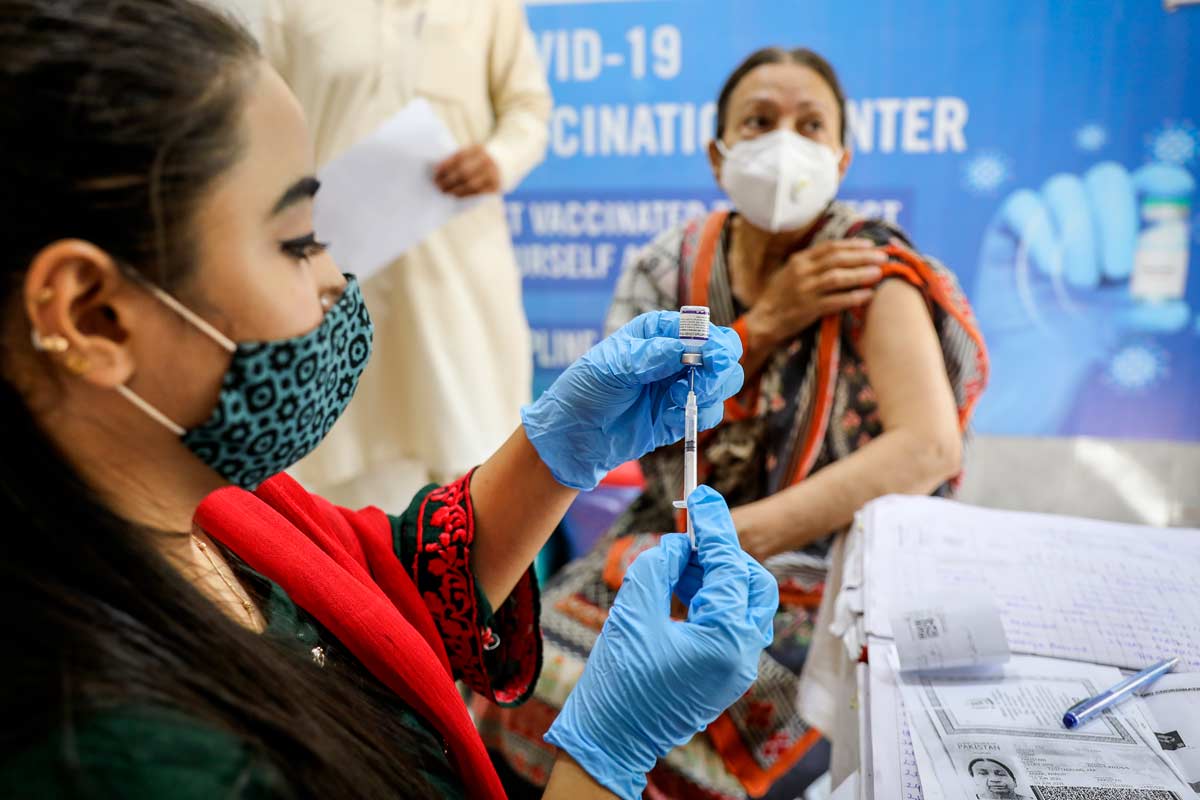

The same barriers exist for HPV vaccine uptake. People don’t understand sexual transmission; they’re not connecting the dots. Only a tiny fraction is actually aware. While 151 countries have introduced the HPV vaccine, we still struggle with awareness here. We even fear how to break the news of deaths to families because they lack basic knowledge... There is lack of health awareness, lack of information, lack of communication. We need to advocate in the language of our communities, guide them to get vaccinated as vaccines work and save lives.

How do you approach communicating with families, especially where cultural sensitivities exist?

Dr Saima: I believe strongly in girls’ education. Mothers are generally receptive; fathers often have questions, but if you tell them the truth and the facts, they’re receptive too.

We have early marriages in Pakistan [involving] girls as young as nine in some rural areas. In disaster-affected places like flood zones, families sometimes marry daughters off for perceived protection. There’s also child abuse and gender-based violence in many areas; we must cover those girls. People need to know that this is a disease, that transmission happens in certain ways and that a vaccine works because a young immune system produces strong, long-lasting antibodies.

I always advise people to go to learned sources, to call 1166 and seek reliable information from trained professionals rather than believing rumours. Public awareness is also our primary responsibility: we must reach the masses. If we can make teal ribbons visible for cervical cancer like pink ribbons for breast cancer, it will help normalise the conversation.

You’ve done a lot of direct outreach and advocacy. What did that look like in practice?

Dr Saima: I learned that parents are interested but they need accessible information. That is why I started doing public webinars for parents; anyone could join. Through parents I found that some schools were already privately procuring HPV vaccines for girls.

Community engagement consumed me! I was sleeping maybe four hours after 44 hours! I engaged with people in different groups, did advocacy sessions on Zoom with Al-Huda and various school principals, and made videos in 12 regional languages. I made video messages by renowned local gynaecologists in those languages and shared them widely.

I went to six schools in one day on average across Islamabad. In E-8 sector, we achieved more than 90% coverage because I was personally going there and giving sessions. We hung banners everywhere: public places, parks, near mosques, in markets. We visited the schools regularly. We faced resistance, of course, but we persevered.

You mentioned an intense situation in one area with withdrawals. Can you walk us through that?

Dr Saima: Yes, that story captures why rapid, empathetic action matters. In one school there were 150 withdrawals triggered by a misleading video. We acted quickly: we went to other schools and got 200 girls vaccinated the same day to prevent the misinformation from spreading further. Hearing that 200 had been vaccinated, other parents and children began to return. The same day, 50+ girls came to our camp to get vaccinated. The next day 100+ of the 150 withdrawals returned and were vaccinated. On the third day 35 more came. I remember saying to my team, “Even if one more girl comes, we will go and make sure she gets vaccinated.” Originally there had been 366 consents registered in that area, but by the end we vaccinated 1,300 girls there. It was exhausting but energising, and it showed how quickly trust can be rebuilt through direct action.

Were there other school stories you remember vividly?

Dr Saima: Absolutely. We set up a big hall in another school and organised a parents’ meeting. I listened to issues that had nothing to do with the vaccine, like water problems at the school. I listened because listening is the best way to connect. I said: “As you realise that safe water is important for health, similarly the HPV vaccine is important.” I spoke to them for two hours. That day we vaccinated more than 350 girls. The rush was hard to manage in the school vicinity so we shifted operations to the hospital and vaccinated another 400 girls. When I returned to the school the next day, all the principal, teachers and students had gathered. They were cheering and were beating drums for me at the entrance. It was an incredible, emotional moment.

How did you address needle fears and other concerns that parents or children had?

Dr Saima: We made sure to address needle fears proactively. If a girl faints because of fear, people sometimes wrongly link that to the vaccine. So, we trained teams to manage fainting and anxiety, and explained that such reactions are about fear, not the vaccine itself. I remember a parent who was a doctor called me about his 11-year-old daughter who had seen many anti-vaccine videos online and refused the vaccine. He asked me to speak to her. I did – she had informed, specific questions, and I addressed each one. She eventually got vaccinated. Children today are different: they are informed and opinionated. Talk to them honestly and clearly.

There are some moments with children that sound especially touching. Can you share any?

Dr Saima: One sticks with me: a nine-year-old girl came and asked about her ten-year-old sister who had blood cancer. She wanted to know if her sister could have the vaccine. I said we would look into it personally and guide them. If a nine-year-old can appreciate the importance of the vaccine and care for her sister, that’s a powerful reminder of how much children understand.

Let’s make the teal ribbon visible everywhere, like the pink ribbon for breast cancer. We owe it to every mother, daughter and young girl to protect them from a preventable disease. This is not just a health issue; it is a movement for dignity, protection and hope.

This was in E9 school, where there were 450 girls in one batch and more than 900+ girls across groups. I did two special sessions in one day. For the young girls I made a special presentation, not the routine PowerPoint for parents. I used friendly, relatable language and imagery. I used Teeku, the well-known mascot from FDI, and made a rhyme – Daikho Daikho Teeku Aya, Sath Apna Ceco Laya (“Look, look! Teeku’s here today –and he’s brought Ceco to play!). I told them that Ceco is short for Cecolin, which is the injection they are getting and that it’s their right to know the name of the injection they were given.

You’ve apparently been everywhere in the media. Give us the rundown.

Dr Saima: I went on morning shows, cooking shows, talk shows, radio, TV, social media, every platform people watch. I wanted to be where the masses are: to talk to the agriculturalist, the cleaner, the banker, everyone. I needed to speak to my nation in many different languages and formats. I not only went to school and hospitals but offices like banks, telecom, IT, etc. All my posts, webinars and videos made sure I was everywhere. I didn’t refuse any platform.

How have you coordinated with government health teams and volunteers?

Dr Saima: When our Director General, Federal Directorate of Immunization, Dr Soofia Yunus, said we needed to engage schools, the government started calling for volunteers among clinicians and partner organisations to support vaccination drives. We were there to support both advocacy and the vaccination activities. I asked the government to write simple appreciation notes to volunteers. People are not always looking for money; recognition motivates. CSOs shared guiding material with volunteers.

Looking forward, what gives you hope for Pakistan’s future in cervical cancer prevention?

Dr Saima: The girls themselves give me hope. Pakistan’s future is these girls – their spark, their curiosity, and the seriousness of their questions. Their concern about parental permission shows how self-aware they are about their health. If they take it on, they can turn the table favourably on cervical cancer. They think differently; they are informed in ways older generations may not expect. Most important, these are different times and different girls.

Have you read?

How many girls have been vaccinated so far, and what does that mean to you?

Dr Saima: As of now, around nine million girls have been vaccinated out of our target of 11 million (which is 90% of the national population of 9- to 14-year-old girls in Pakistan). That milestone makes me proud and hopeful. It shows that when communities understand and when systems respond, we can protect a generation.

If you could give one final message to healthcare providers, policymakers, parents and young people, what would it be?

Dr Saima: Our message must be clear and inclusive: public awareness is our collective responsibility. Healthcare providers should lead by example and speak honestly. Policymakers must prioritise health education and create supportive systems for vaccination and screening. Parents should seek trustworthy sources like 1166 and trained professionals rather than word of mouth. Young people – especially girls – should be empowered: their questions are real and valuable. Let’s make the teal ribbon visible everywhere, like the pink ribbon for breast cancer. We owe it to every mother, daughter and young girl to protect them from a preventable disease. This is not just a health issue; it is a movement for dignity, protection and hope.

Thank you, Dr Saima. Is there anything else you’d like readers to know?

Dr Saima: We must keep listening, keep educating, and keep acting – because every life we prevent from being lost to cervical cancer is a life worth fighting for. Cervical Cancer Free Pakistan In Sha Allaah.

About Dr Saima Zubair

Dr Saima Zubair, MBBS, MMCH, FRCOG is a leading consultant in maternal health and an obstetrician-gynaecologist at the Islamabad Institute of Reproductive Medicine (IIRM), Pakistan. She serves as the Coordinator for International and National Chapters of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Pakistan (SOGP) and Managing Editor of the Journal of SOGP. Founder of the Pak Virtual Hospital (PVH) – Pakistan’s first virtual hospital launched during COVID-19 – she is also the Project Coordinator for the FIGO LDI: REACH project and is an active member of national technical groups including RMNCAH&N TWG and NITAG.

A Governor’s Gold Medal recipient, Dr Zubair has pioneered initiatives such as Family Planning by Family Physicians (FP by FP) and the Samra Noor Initiative (SNI) for COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy. She co-founded K-Cares for critical care training in Balochistan and heads the NGO ARMAN, recognised by WHO for resilient frontline service. Passionate about women’s health, advocacy and health system strengthening, she continues to champion equitable reproductive and maternal care across Pakistan.

More from Areej Javed

Recommended for you