A Deadly Alliance – War and the Pandemic Influenza of 1918

As World War I reached its climax, a terrible influenza pandemic broke out. By summer 1919, it had claimed many more lives than the conflict – but the conflict, researchers say, helped create the conditions for the devastating spread of the so-called “Spanish Flu”.

- 30 July 2021

- 6 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

At a glance

- World War I may have been the first major conflict in which battle-wounds killed more soldiers than disease. This was modernity: sanitation and vaccination were better, and weapons were more destructive.

- But war still created optimal conditions for infections to spread, and even evolve. In 1917, the enormous British military encampment at Étaples was struck by an “unusually fatal” and apparently novel lung disease. Some modern historians speculate that this respiratory virus was the pre-mutation precursor to the Spanish flu.

- Whether the so-called Spanish flu originated out of barracked conditions, there’s no question that it spread with returning troops in 1918. By the summer of 1919, the pandemic was waning, leaving the planet littered with between three and 12 times more casualties than the conflict had taken.

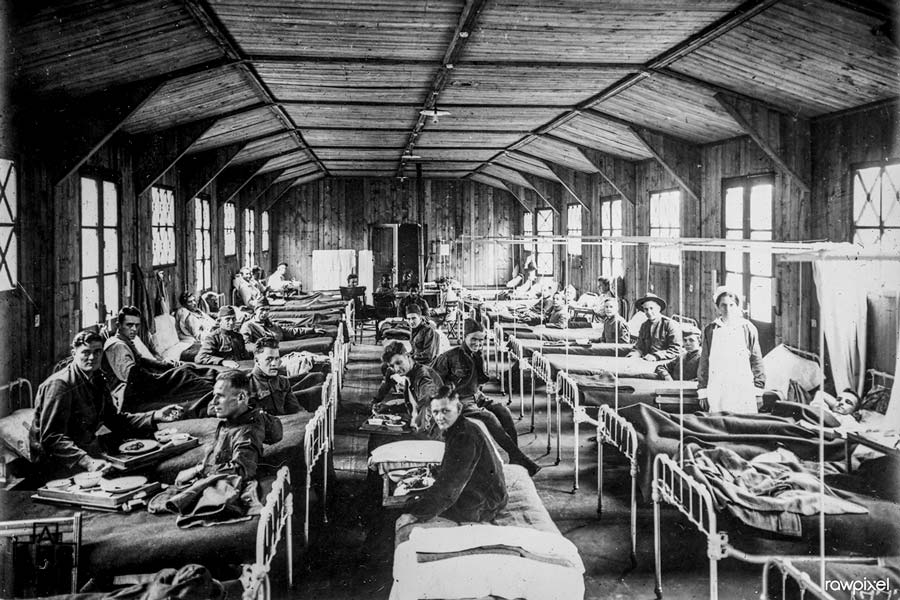

In January 1917, two and a half years into World War I, two million British soldiers were huddled in a line of trenches stretching from Dunkirk almost to the source of the Somme. Winds from over the North Atlantic swept in a season of uncommon cold and unusually high rainfall: the trenches were freezing and muddy; there were rats. It wasn’t a great surprise when some hospitals filled up with more sick than wounded. Everybody knows that infectious diseases love a war. During the Crimean War, after all, more than twice as many soldiers had died of illness than in combat, and the British Army had seen a similar pattern of fatalities during the South African war of 1899 – 1902.

Though the pandemic’s origin is still debated, it’s clear that the war created ideal conditions for the mutation and spread of such an animal virus.

During the Spanish-American war of 1898, only 379 soldiers had fallen on the battlefield, but more than two thousand had succumbed to typhoid. And yet, there had been some progress in infection control since the late 19th century, when it became commonly accepted that that tiny pathogenic organisms caused communicable illnesses. Chlorinated antibacterial washes were deployed generously at the front, and most of the soldiers in the trenches were vaccinated against smallpox, cholera and typhoid before they shipped out.

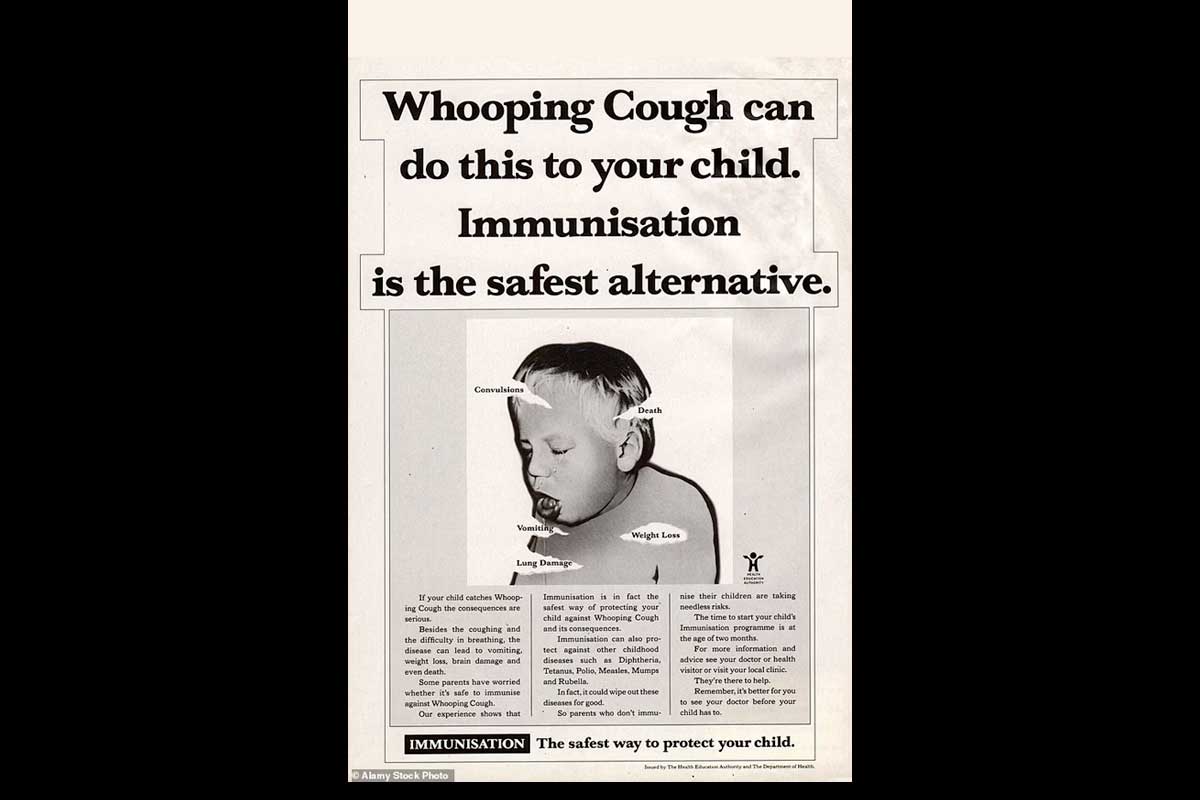

But no vaccine against influenza had yet been discovered. That winter, at Etaples, an enormous British military camp on the coast of France with twenty thousand hospital beds, cases of an “unusually fatal” form of “purulent bronchitis” began to crop up. Patients were breathless and turned blue, noted a 1917 report in the Lancet; their symptoms progressed fast. By January the numbers constituted “almost a small epidemic” – except that the bug didn’t seem to be spreading from human to human. Its cause remained mysterious.

In 2019, virologist Professor John Oxford and military historian Douglas Gill proposed that the semi-forgotten Etaples outbreak, along with a second, similar outbreak at an army base in Aldershot, constituted “a portent of the disaster to come”: 1918’s pandemic influenza, misleadingly called the “Spanish Flu”, which would infect almost one in three of the world’s population before it had run its course.

That pandemic virus, explain the researchers, was a bird-flu, which had likely mutated to move out of the base of the lung and into the upper airways, allowing it to become transmissible – via coughing – between human hosts. Was the sickness at Etaples its pre-mutation precursor? As Oxford and Gill point out, the Aldershot doctors spotted a link: “in essentials the influenza pneumococcal purulent bronchitis that we and others described in 1916 and 1917 is fundamentally the same condition as the influenza pneumonia of this present pandemic,” they wrote in the Lancet in 1919.

Have you read?

Though the pandemic’s origin is still debated, it’s clear that the war created ideal conditions for the mutation and spread of such an animal virus. Etaples, for instance, was home to hospitals, poultry yards and pig sties. 100,000 troops – 100,000 young men with stressed immune systems – could be quartered there at any one time, with over a million moving through during the course of the war. Epidemiologist John Mathews explains: “As people living in close proximity became infected, and the number of infected people and viruses transmitted grew, the overall size of the viral population grew rapidly. With many more viruses being made, there was greater scope for the emergence of new mutations that could grow and spread more readily in humans.” And, with troops moving across continents to reach the front, the First World War also offered unprecedented opportunity for the virus to travel great distances. People were “more liable than ever before to be exposed to any new form of the flu,” according to Mathews.

According to the final, horrific tallies that followed the November 1918 armistice, World War I qualified as the first major war in history in which weapons had killed more combatants than disease. But you can’t call a ceasefire on a pandemic, nor designate non-combatants ‘off limits.’ The pandemic carried on.

Having typically hitched a ride to new territory with a convoy of returning soldiers, the virus blazed through civilian populations all over the world. Vessels carrying the 150,000 African troops who had fought on the European fronts brought the virus to the ports of Freetown, Cape Town and Mombasa. Four percent of Freetown died in three weeks; South Africa and Kenya lost some 4-6% of their populations. It arrived at Brevig Mission, a tiny Inupiat village on the Russian-facing coast of Alaska, in November 1918. 90 percent of the town’s inhabitants were dead in five days. Stowed away on troop ships, the virus made landfall in Bombay in June 1918, and quickly spread along India’s vast rail network as infected soldiers journeyed home. By December, it had claimed possibly as many as 18.5 million lives on the subcontinent. Persia lost between 8-22 percent of its population. In America, where the first cases of the pandemic flu had been recorded in March at a Kansas barracks, overall life expectancy plummeted by 10 years.

Globally, somewhere between 50-100 million people died of the influenza before the pandemic finally waned in the summer of 1919. Its body-count would finally outstrip the War’s by between 3 and 12 times.