Tackling Cameroon’s worst cholera outbreak in decades

Health experts in Cameroon have called for vigilance and the respect of basic hygienic rules as the country grapples with a severe cholera outbreak.

- 13 April 2022

- 5 min read

- by Nalova Akua

Cameroon is racing against time to halt the spread of a cholera epidemic that has killed at least 62 people and infected some 2,097 others since October 2021. Six of the country’s ten regions – Centre, Littoral, Far North, North, South, and South-West regions – have reported at least one case amid daily increases in the incidence rate.

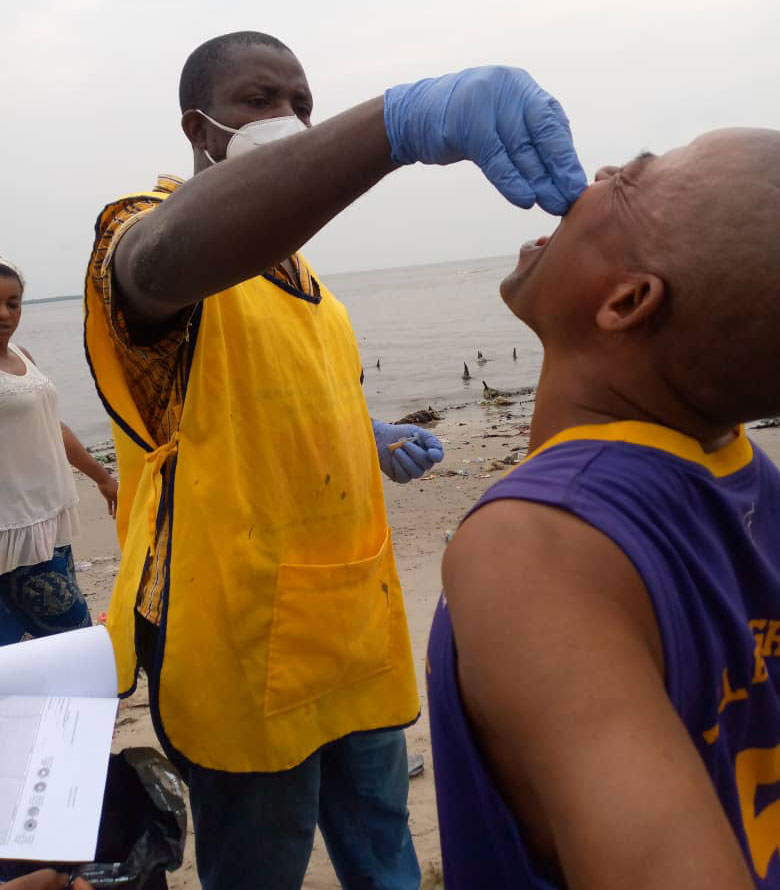

The daily rise in the number of cholera cases has triggered a rush for cholera vaccines in the country. Just over two million doses have been approved from the Gavi-funded oral cholera vaccine (OCV) global stockpile to tackle the outbreak, enough to vaccinate more than a million people.

“Cholera has been moving from one district to the next, from maritime districts to the mainland districts,” says Dr Filbert Eko Eko, Public Health Delegate for South-West Region.

Credit: Filbert Eko Eko

“The South West Region is one of the border regions to Nigeria and it’s also facing a humanitarian crises. Trans-border movement is so frequent, and it is difficult to control the movement of people between Nigeria and Cameroon. For this reason, it is also difficult to check their health status. If we could control the trans-border movement, it would be easier for us,” Dr Eko Eko says.

The situation is exacerbated by social and cultural factors, including religious beliefs and stigmatisation, as well as the unsafe management of bodies.

“There are also areas with difficult terrain, making it difficult to provide the necessary facilities like potable water and decent sanitary conditions. There are situations where we end up with faeces in the rivers where people also draw water from,” adds Dr Eko Eko.

For Dr Eko Eko, dealing with the underlying factors that cause cholera is critical in eradicating the epidemic.

He says, “The cholera epidemic usually starts during the dry season, which is when there are problems with water. We need to provide potable water to the community. We also need to check their sanitary conditions, especially faecal disposal, while also ensuring that the water they drink is healthy enough.”

Credit: Filbert Eko Eko

Cameroon’s Minister of Public Health, Dr Malachie Manaouda admits that the epidemiological situation with cholera throughout the country has evolved.

“A multidisciplinary team is hard at work to contain this epidemic, but also to prevent its spread to the other regions,” Dr Manouada says.

“Free case management, sensitisation and the disinfection of households and communities are effective; water purification kits were made available to affected communities and the surveillance system has been put on alert. Reactive vaccination campaigns are being organised.”

Have you read?

The daily rise in the number of cholera cases has triggered a rush for cholera vaccines in the country. Just over two million doses have been approved from the Gavi-funded oral cholera vaccine (OCV) global stockpile to tackle the outbreak, enough to vaccinate more than a million people. Half of these have already been shipped and campaigns are underway. More than 100,000 people in the South-West Region have so far received the vaccines.

On top of these reactive vaccination campaigns, the country is also working in a revised national cholera control plan that will include the conduct of preventive campaigns in cholera hotspots.

“I was dispatched to come and collect cholera vaccines for some staff of my company,” Ndomo Standley, a worker at SINOMACH water treatment plant in Yaounde, says, moments after collecting 28 doses of cholera vaccines from a vaccination centre. The company has more than 300 employees, the majority of whom have already been vaccinated.

“The company is making sure that every employee is vaccinated against cholera, and COVID-19 for everyone to feel safe. The company monitors the emergence of outbreaks and takes appropriate measures. Given the rise in the number of cholera cases in Cameroon, management is simply taking counter measures to protect its workers,” Standley adds.

Another Yaounde inhabitant, Nkeng Manon, explains that he has been in a state of panic since the first case of cholera was reported in Cameroon, but now feels protected after taking the vaccine.

Credit: Filbert Eko Eko

Cameroon has partnered with international bodies and organisations including WHO, UNICEF, Doctors Without Borders, the Norwegian Refugee Council, and also civil society organisations, to sensitise citizens to the dangers of cholera, as well as manage cases.

“WHO assisted the Ministry of Health by establishing the Incident Management System Team at the WHO Cameroon office to provide technical and financial support across five main pillars of the response: coordination of partners, health operations, planification and surveillance, operational support logistics and administration as well as finance,” says Dr Jean de Dieu Iragena, Cholera Incident Manager, WHO Cameroon Office.

Dr Iragena does, however, feel that Cameroon’s cholera response plan needs to be supported by more partners "to quickly reverse the incidence and mortality".

“We must redouble our efforts and together with the Ministry of Public Health and other partners, we cannot miss this momentum to end this epidemic and put Cameroon on the path towards cholera elimination by the year 2030,” Dr Iragena says.

Gavi started funding the global cholera vaccine stockpile in 2013. Since the stockpile was launched, millions of doses every year have helped tackle outbreaks across the globe. In the 15 years between 1997 and 2012, just 1.5 million doses of oral cholera vaccine were used worldwide. In 2021 alone, the stockpile provided 29 million doses for emergency and preventive use across the globe.