Community-driven care cuts risk of child deaths in Togo by nearly a third

For just US$ 10 a year per person, an integrated primary health care approach led by community health workers has proven to be highly effective at saving lives.

- 19 February 2026

- 6 min read

- by Priya Joi

At a glance

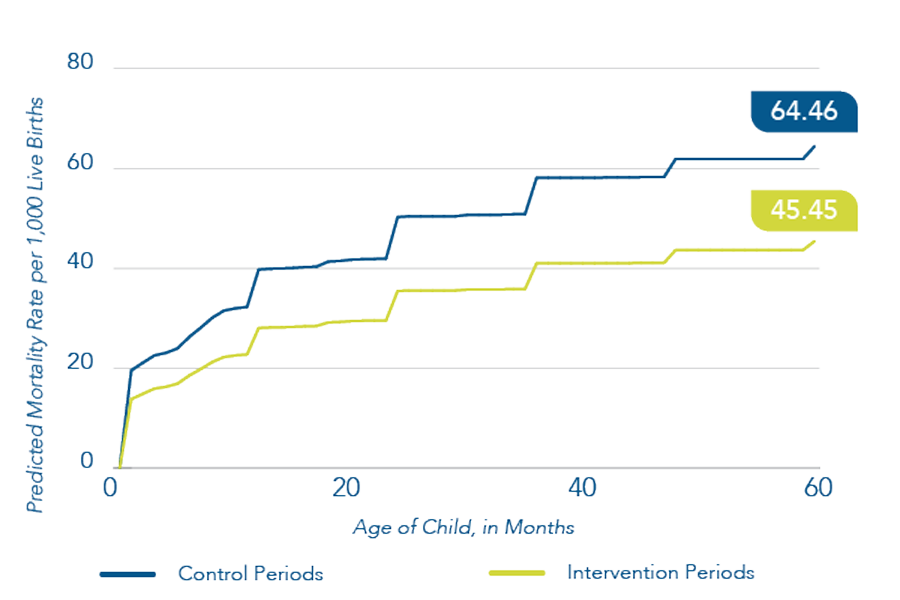

- An integrated primary health care model in northern Togo cut the risk of death before age five by 29%.

- The approach combines proactive community health workers, fee-free care and strengthened rural health centres.

- Delivered at scale, the programme cost around US$ 10 per person per year and was designed to be rolled out in similar settings in low- and middle-income countries.

It’s a weekday morning in a health centre in Adabawere, a village in the Kozah district of Togo, West Africa, and Madeleine Biniwe Teou is a familiar figure. A community health worker (CHW) supported by Integrate Health for over a decade, she serves as a critical link between the community and the local health centre.

That morning, she was helping the nursing staff run a vaccination day – filling in vaccination cards, scheduling follow-up appointments, and tracking children who had missed doses. “We are trained. We know what we are doing,” she says.

But Madeleine’s workday starts at sunrise, before she has even left the house. “In the morning when I wake up, women are already at my door – some for family planning, others bringing children who are not feeling well. I treat them at home before heading out into the field around 07:30.”

Going door to door, she conducts proactive case-finding for children under five, screens for malaria, pneumonia, malnutrition and diarrhoea, monitors pregnant women, and refers serious cases to the health centre.

Behind the daily routines of CHWs like Madeleine lies an integrated health system approach – one that has now been evaluated in a large clinical trial.

A clinical trial testing the Integrated Primary Care Program (IPCP) in northern Togo cut the risk of children dying before age five by 29% and, what’s more, it did so at a cost of US$ 10 per person per year.

Primary health care for all

At a moment when the World Health Organization (WHO) and member states are focused on embedding primary health care (PHC) as the backbone of universal health coverage, Integrate Health’s experience in Togo provides a data-driven view of how that future could look on the ground, says co-author Jessica Haughton, faculty in the Department of Pediatrics at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, USA and a collaborator with Integrate Health, New York, a non-governmental organisation whose mission is to make PHC healthcare accessible for all.

Have you read?

The study, published in Pediatrics in November 2025, tested a model that combines eliminating point-of-care fees, proactive care by community health workers, clinical mentoring as well as structural improvements of health centres in countries like Togo with critical shortages of medical professionals – there is just one doctor per 10,000 of the population.

Haughton explains that the aim of their study was to demonstrate that an integrated model that reduces child mortality by a third “is possible in other places at a low cost and can be replicated in rural areas with few doctors”.

Connecting services

Integrate Health (to which Gavi contributes funding) first tested the IPCP in a pilot study of 10,022 households co-implemented by the Ministry of Health in northern Togo, which showed a 30% reduction in risk of under-five mortality between 2015 and 2020.

When the programme was implemented at scale, there was a similar 29% reduction in the risk of death for children under five. The expanded programme serves four districts, more than 180,000 people, and the study sample included 50,404 households over five years.

The programme was designed to address any potential barriers to accessing healthcare in a rural area. At the facility level, clinical mentors visit rural health centres to support nurses with tasks such as planning for malaria season, ensuring pharmacy stocks and applying clinical protocols, while structural supports bring basics like electricity and water to centres that often lack them.

Community health workers “proactively go to the community and look for sick kids, babies and mothers that need care”, encouraging women to complete antenatal visits, checking for danger signs and linking families to facilities, Haughton told VaccinesWork. Removing fees for women and children is the final piece that eliminates an important barrier to accessing care.

“The results of these interventions being in place are often that people have greater vaccination coverage, higher consultations, more prenatal visits, kids are seen more often and there is increased access to care overall. This is why we believe that the reduction in child mortality is because of the integrated approach we used,” says Haughton.

Teou, as a community health worker, has witnessed the transformation firsthand. “When we started, I saw so many cases of serious illness. Cases of meningitis. Before, you could bring a child into the world, but they would not reach their fifth birthday.”

The introduction of fee-free care through the programme changed everything: “Mothers no longer hesitate to bring their children to the health centre. Women here often tell me that the money they used to spend on care, they now keep part of it for their household.”

Community health workers are critical

Camille Arimoto, Integrate Health’s Communications and Advocacy manager, told VaccinesWork that in global declarations and resolutions, while PHC is acknowledged as a key part of achieving universal healthcare, “no one is talking about community health workers as being a critical part of delivering this care.”

Dr Désiré Dabla, Integrate Health’s Research Manager in Togo, added that trained, salaried and supported CHWs were vital to the success of the programme. Yet in many parts of the world, including West Africa, CHWs are underpaid or unpaid for their work.

This is part of a bigger, widespread problem of health systems in low- and middle-income countries relying on volunteers to deliver community care – a study from the Center for Global Development estimated that across Africa, as many as 86% of CHWs are unpaid.

However, the costing of the Togo study “was done based on the fact that community health workers at Integrate Health are paid,” said Dr Dabla, noting that this demonstrates such a model could be “economically possible” for governments to implement.

Now, said Haughton, the organisation is implementing the IPCP in Guinea and hoping to expand the model to other countries in West Africa. “Seeing the results from the five-year study of the scaled programme gives us confidence in its effectiveness and information on how to improve implementation as we continue to expand and make primary health care accessible for all.”