Getting screened for cervical cancer is choosing self-preservation

Like most Zambian women, 33-year-old VaccinesWork contributor Fiske Nyirongo had never been screened for cervical cancer. That changed this August, after the death of a prominent campaigner.

- 10 September 2025

- 6 min read

- by Fiske Nyirongo

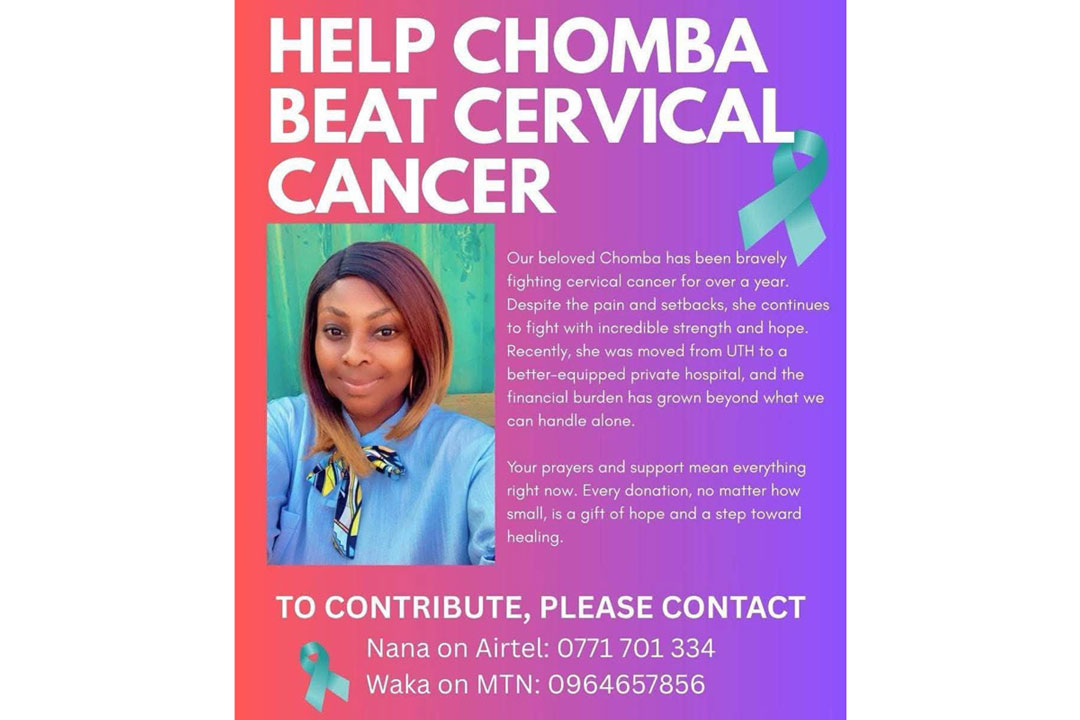

On a warm afternoon in July 2024, a former classmate sent me a TikTok video. In it, a soft-spoken woman with a bright, open face spoke directly to the camera.

“Good morning family, good morning friends. This is the 7th of February 2024. In case you don’t know who I am and you come across this video on any of my platforms, I am Chomba Nakazwe. I was diagnosed with cervical cancer in 2023, December 22, and this has been my fight…”

My stomach dropped. Chomba looked like someone I might know – a friend, a cousin, a sister. I interrupted the video. But Chomba’s face and voice resurfaced across platforms, and soon, her name appeared in everyday conversations.

A few months later, she was making fundraising appeals for treatment in Tanzania. Zambia’s Cancer Diseases Hospital was under renovation, and in a country with limited tertiary care infrastructure, temporary closures can make foreign travel the only means to access specialist treatment.

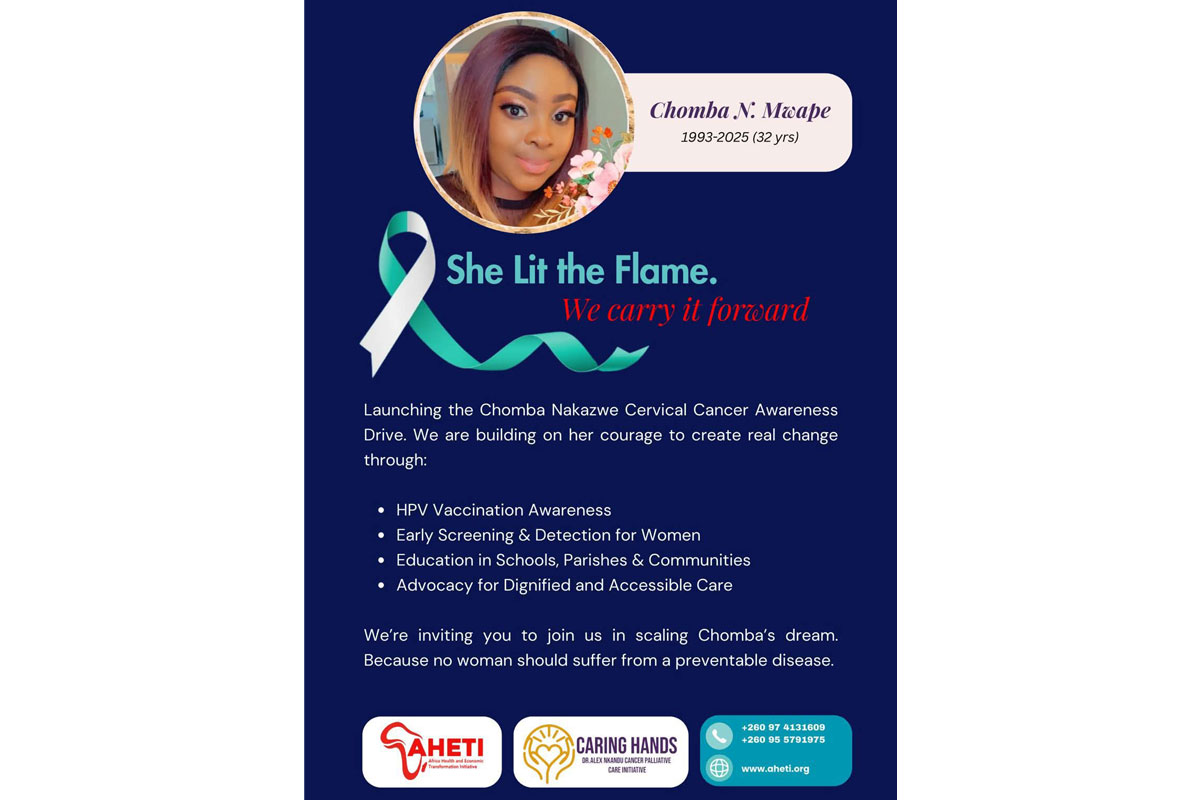

More than 60% of cervical cancer patients in Zambia succumb to the disease but Chomba’s death, in April 2025, was shocking. She was only 32. She had three children under ten. She had dreams.

Even in a regular year, resources for cancer care are relatively thin on the ground in Zambia. Oncologists are few – in 2018, there were just seven of them in the country – and cancer rates are high, with more than 15,000 new cases diagnosed each year. Cervical cancer accounts for a staggering 23.8% of those cases.

Shocking – and shockingly common

More than 60% of cervical cancer patients in Zambia succumb to the disease, but Chomba’s death, in April 2025, was shocking. She was only 32. She had three children under ten. She had dreams. Her loss wasn’t just a moment of national mourning, but an eye-opener. Despite the high rates of cervical cancer afflicting Zambia and the region at large, we Zambians know relatively little about it.

From First Lady Mutinta Hichilema’s Facebook post – praising Chomba for “inspiring countless women to prioritise their health” – to advocacy pages sharing her experience, her story became a rallying cry for early detection and equitable care.

Never too late

I’m a 33-year-old Zambian woman, unmarried and without children. I’ve also been writing about health for five years, but until recently I – like most Zambian women – had never been screened for cervical cancer. If I’m honest, I hadn’t even seriously considered it.

Zambia’s national campaign currently offers free HPV vaccination to girls aged nine to 14, aiming to protect them prior to exposure to the virus. It’s an opportunity I mildly envy our young sisters. The vaccine is capable of preventing 90-plus percent of cervical cancer cases.

When I first saw Chomba’s video, I shut it down almost instinctively. Was it that I didn’t want to confront the risk? According to a 2021 paper, just 22% of women in Zambia had participated in nationwide screening programmes, and those women skewed HIV-positive, more educated and older – the majority of them falling in the 35–49 year age bracket. But Chomba was younger than me: no more excuses.

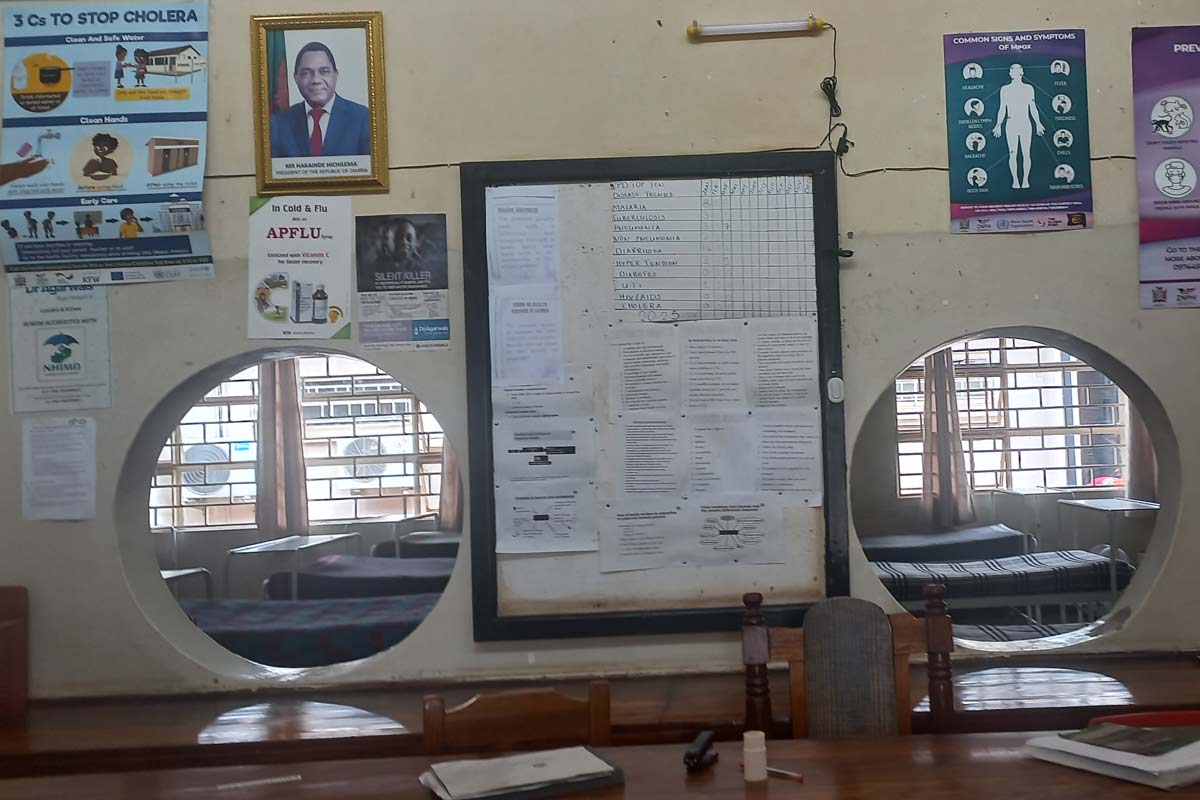

In May 2025, I began researching my options, looking for a clinic that was accessible, responsive and respectful. During my twenties, I had encountered stories about gynaecologists or nurses who were unnecessarily harsh to young women accessing reproductive services, especially if the woman was single, or from a lower-income background.

After speaking with friends and combing through reviews, I chose the Planned Parenthood Association of Zambia (PPAZ) clinic near Lusaka’s central business district. They were easy to reach by phone, answered my questions patiently, and offered screening at a fee of 200 kwacha – approximately US$ 8.

Have you read?

For women aged 25 and above, screenings are available free of charge at government hospitals and clinics, part of an effort to reach every woman who needs them. While this free option is commendable, results can take longer to come out, which can be a barrier to early detection.

Getting checked

On the day of my appointment in August, I arrived anxious but determined. A receptionist greeted me warmly. Her easy manner softened my nerves.

I explained to Olivia, the nurse/midwife who saw me, that this was my first screening and that I was worried. She asked about my last menstrual cycle, whether I’d begun breast cancer screening, and gently walked me through the process. I asked questions too – about the recommended frequency of screenings, HPV, and what happens if abnormalities are found.

“Every two years is the recommendation for us in Zambia,” she said. “If it’s caught early, you have a better chance of surviving. That’s why screening is so important.”

The procedure was mildly uncomfortable but quick, taking less than ten minutes. Olivia mentioned there was a backlog due to a recent mass screening of utility company employees, meaning that my results would take longer than usual to reach me. According to Nurse Olivia, large groups often visit the clinic during workplace health days – wellness initiatives typically prompted by awareness campaigns led by medical personnel, the Ministry of Health, or individuals personally affected by cervical cancer, including both survivors and families who have lost loved ones to the disease.

Next was the wait. I felt nervous. But I also felt grateful. Grateful that I could take this step. Grateful that I had options. Grateful that Chomba’s story, though tragic, nudged me into action. I reminded myself that even a worrying result was good news – it could lead to curative care. Still, when the results returned normal, I felt a quiet flood of relief.

My younger sisters have more options

I have not explored the HPV vaccine for myself yet, and I am not sure what access looks like for women outside the target age group. Zambia’s national campaign currently offers free HPV vaccination to girls aged nine to 14, aiming to protect them prior to exposure to the virus – this, the World Health Organization has established, is the optimal window for vaccine impact.

Screening, like vaccination, is an act of deliberate self-preservation – a gift we owe ourselves, and more accessible than some think.

It’s an opportunity I mildly envy our young sisters. The vaccine is capable of preventing 90-plus percent of cervical cancer cases. In 2023 alone, the Ministry of Health sought to immunise over 1.42 million girls during a six-day campaign – cancer rates in the next generation should be far lower than in mine, or in the generations before mine.

Had I belonged to the vaccinated generation, my anxious experience of screening might have felt very different. In Scotland, where HPV vaccination has been routine for girls aged 12 to 13 since 2008, a 2024 study found no cases of cervical cancer in fully vaccinated women from the first immunised cohort. As public health expert Dr Mujajati has observed, “For girls vaccinated in early adolescence, we expect screening to shift from frequent interventions to reassurance, confirming protection rather than searching for disease.”

Still, screening, like vaccination, is an act of deliberate self-preservation – a gift we owe ourselves, and more accessible than some think. PPAZ and other clinics throughout Zambia now offer walk-in screenings, often quick enough to fit between errands. I hope more women take that first step. I hope we talk about it more openly, without shame or fear. I hope we remember Chomba Nakazwe-Mwape not just in mourning, but in action.