A shot at survival: Zambia prepares to roll out malaria vaccination

Zambia sees an estimated 3.6 million cases of malaria each year, and thousands of deaths. Health workers and parents hope the vaccine can curtail that toll.

- 22 October 2025

- 4 min read

- by Fiske Nyirongo

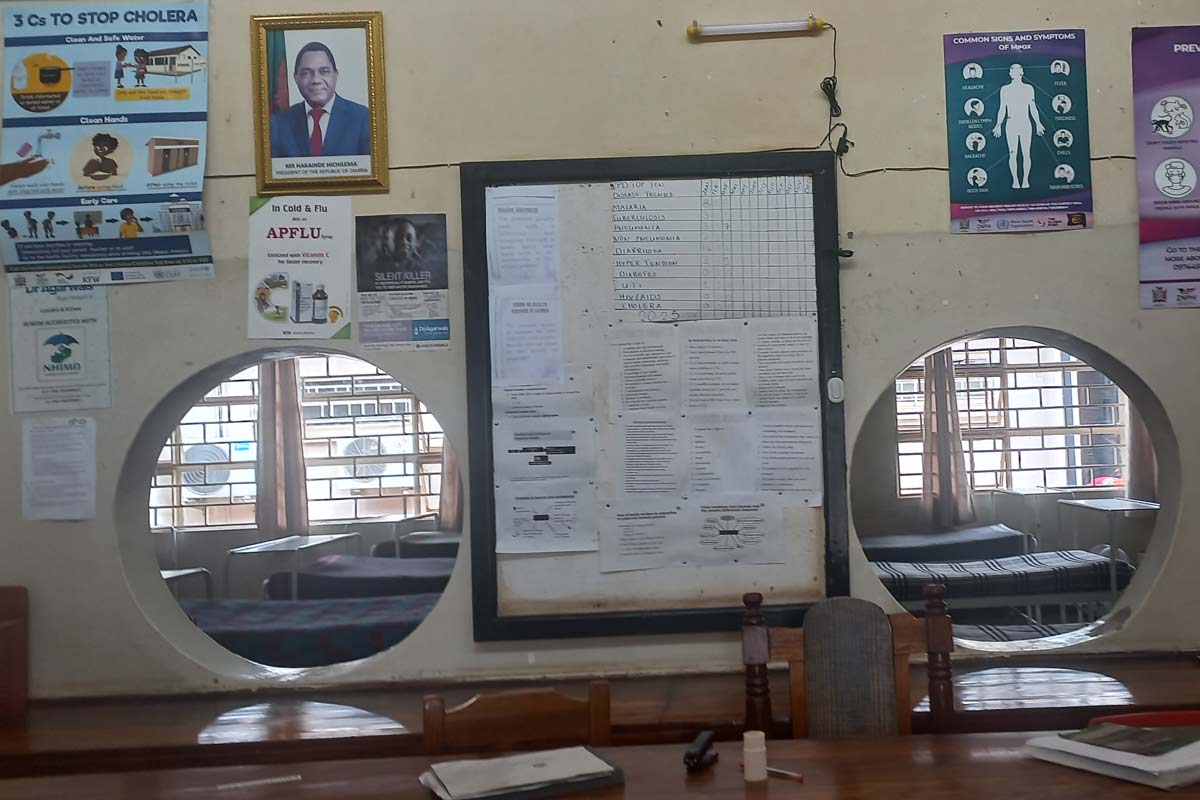

Josephine Mpundu walks into Chongwe Rural Health Centre with her nine-month-old child nestled in her arms. The baby babbles cheerfully, the sound rising above the hum of conversation in the outpatient wing. But just two weeks earlier, that same child was inconsolable – feverish, crying, and in pain.

“We thought it was just a flu,” Mpundu recalls. “But after a few days of high fever, we knew we had to go to the hospital.”

The diagnosis was malaria. Baby Mpundu was admitted for three days.

“It was very hard for me to be away from home. Taking care of a sick baby is not easy, and it was painful to see them suffer.”

A safety net too few

Like many families in Chongwe District, the Mpundus do their best to prevent mosquito bites. But their options are limited.

“We only have one mosquito net, which we got at the [baby’s] nine-month appointment but when it’s dirty, we sometimes go days without using it.” Mpundu suspects that gap in protection is when her child was bitten. For her household, the net is the only malaria intervention they can access.

Susan Chola, another Chongwe resident, was diagnosed with malaria a few weeks ago. She believes she contracted it while attending a funeral. “I use a net and burn mosquito coils at home. But at the funeral, I was outside a lot and didn’t take precautions. Two days later, I had a fever and body aches. I tested positive the next day.”

Both Mpundu’s child and Chola were treated and have since recovered. But their stories highlight a persistent truth: malaria remains a threat, and standard precautions – while helpful – are no guarantee.

Though malaria incidence in Zambia decreased between 2015 and 2023, 2023 still saw an estimated 3.6 million cases and more than 8,500 deaths, according to the most recent World Malaria Report. As elsewhere, chidren under five are especially vulnerable to the parasitic infection, with a 29% prevalence rate in this age group in Zambia.

Violet Mwanza, Chongwe’s District Nursing Officer (DNO) says not even the off-season is a reliable refuge from infection. “Our peak malaria months are March to May, during and immediately after the rainy season,” she explains. “But we still see cases in the dry season.

“Our biggest challenge is limited coverage. Right now, we only distribute mosquito nets to babies at their nine-month measles, mumps and rubella vaccine appointments. That leaves many families unprotected unless they can afford to buy nets themselves.”

But in the country’s hardest-hit regions, that gap in protection is about to get significantly narrower.

Have you read?

A turning point in Zambia’s malaria fight

In October 2025, Zambia will join 23 African countries introducing the malaria vaccine into its routine immunisation programme. The vaccines act against P. falciparum, the deadliest malaria parasite there is, and the most prevalent in Africa. The roll-out, supported by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, the World Health Organization (WHO), and UNICEF, marks a historic step in the continent’s millennia-old fight against malaria.

The Ministry of Health will launch the malaria vaccination programme by offering the first of four recommended doses to over half-a-million children aged six to eight months in high-priority districts. According to Dr Jacob Sakala, EPI Manager, the vaccine will complement existing tools.

“In 2021, only 46% of under-fives used ITNs, and just 39% of households received indoor spraying. We’ve been allocated 532,200 doses. In this initial phase, we’ll vaccinate children aged six to eight months to ensure we have enough stock for the full four-dose schedule.”

The roll-out prioritises districts with medium to high malaria incidence, especially rural and remote areas. Training has already been conducted in the selected 83 of Zambia’s 116 districts, equipping provincial and district supervisors, health workers, and community volunteers to track and vaccinate eligible children.

A promise for families

Though Chongwe District is not part of the initial roll-out, the anticipation is palpable. Health workers like Mwanza are already thinking ahead, and families are beginning to imagine a future where malaria no longer disrupts their lives with bitter regularity.

“We’re not yet a participating district, but the vaccine will be a welcome tool in our fight to end malaria,” says DNO Mwanza. “We’re happy the country is taking this step forward.”

In the clinic’s waiting area, Josephine Mpundu holds her baby, who she knows is one of the lucky ones. “I really hope we get [the vaccine] here too,” she says.

For parents like Mpundu, the vaccine represents more than a medical breakthrough. It holds a promise: fewer nights spent worrying, fewer hospital stays and more time to nurture, play, and build a future. It is a chance to protect children around her before the disease ever takes hold.

The RTS,S and R21 vaccines have shown efficacy rates of up to 72% and 75%, used seasonally. They are administered in a four-dose schedule starting in infancy, and when paired with existing interventions, they offer a powerful shield against one of the world’s deadliest diseases.