A Ghanaian doctor’s perspective on COVID-19 vaccine inequity

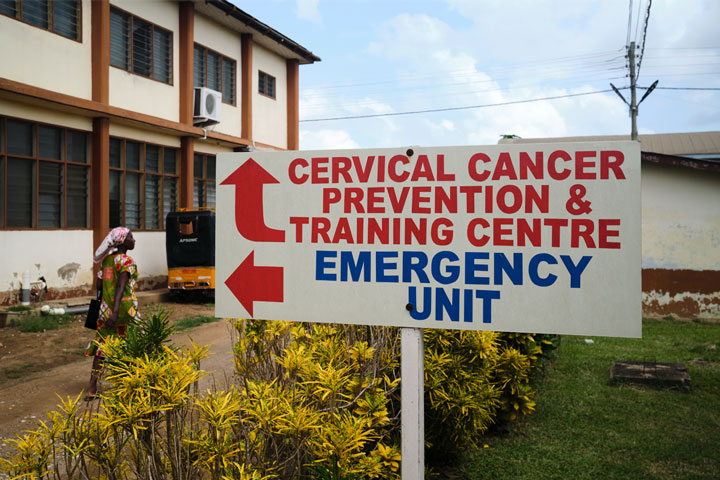

Pre-COVID-19, Ghana’s health system was overburdened. The virus has made everything harder, and vaccine inequity has made it harder still.

- 2 December 2021

- 4 min read

- by Nanama Boatemaa Acheampong

Maame Yaa Acheampong has had a tough few years. The 27-year-old doctor has spent her career working in some of Ghana’s biggest public hospitals. Since COVID-19 arrived in the country, she has been fighting on the pandemic’s frontlines.

“When the pandemic hit, I was working in the child health department,” she says. “At the time everything felt scary. We dealt with some of the sickest kids in the country, running one of the very few paediatric oncology wards at a time when we had very little idea of the effects of COVID-19 in children.

"Poorer nations would benefit significantly from increased access to vaccines, fairer competition for pricing with purchasing and more significant donations from countries that previously secured large doses for their citizens."

“The prevailing feeling through the period was fear. Colleagues sent their vulnerable children to live with parents and other relatives, terrified of passing the virus on. Colleagues in the high-risk group took extra precautions. We rationed masks, sometimes having to stretch one over about ten days. We drove through roadblocks to get to work. And there was the not knowing. All the information was fresh, and we grappled with a whole new system, beginning to see the risks of our job in a very new light.”

In February 2021, Maame Yaa became infected with COVID-19, while working in a busy regional hospital.

“I had seen a number of suspected (and some, later, confirmed) cases of COVID-19 infections that week, working in the outpatient department. It took five days to get my results back, but, by then, I was sure it was positive. I spent three weeks out of work, mostly lying in bed, sweating out a fever or trying to gather enough energy to walk to the bathroom.

“I was out of breath after five steps. My case was considered mild, and I never required a hospital admission, but it was the sickest I had ever been. And the loneliest. Illness is alienating in itself, and an illness that makes you a danger to those you love is so much worse.”

Have you read?

Several of her colleagues also contracted COVID-19 around the same period. Thankfully, she says that everyone recovered, although friends in other hospitals were not so lucky.

“At the time I contracted COVID-19, I was unvaccinated. I received my first shot at the end of March 2021, a month after the first batch of vaccines arrived in Ghana. Having at least partial protection made me feel a lot safer, especially at work. I knew I was privileged to get the vaccine as early as I did, considering how scarce vaccines were due to global vaccine inequity. It also had an impact on my ability to get the second jab, which was almost six months later. I had to travel to the capital city, Accra, for the jab.”

Chronic vaccine shortages mean that there are still large numbers of vulnerable people who have not had access to vaccines. The country’s older population mostly live outside the cities in less accessible areas, where vaccines are in short supply.

“Public health officials are forced to focus on improving coverage in cities, where transmission rates are far higher, leaving those who live outside the areas unattended,” Maame Yaa explains.

The Ghanaian population is still largely unvaccinated, and this has made it harder to control infection rates.

“Our mortality rate has been comparatively low, but could be significantly lower still if we had better access to testing and vaccines. We must also face, in months and years to come, the scores of cases of long COVID-19, in a health system that already struggles to adequately manage persons living with chronic illnesses.

”Poorer nations would benefit significantly from increased access to vaccines, fairer competition for pricing with purchasing and more significant donations from countries that previously secured large doses for their citizens. COVID-19 is a global problem. Unless we begin to truly see it as such and seek to protect all of us and eliminate the disease across regional and national divides, we may be dealing with major global outbreaks for longer than any country is prepared for.”