Whooping cough exploits slender immunity gaps in Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan’s vaccination rates are high – but a recent pertussis outbreak in Tashkent shows that unimmunised individuals remain at serious risk.

- 9 January 2024

- 5 min read

- by Umida Maniyazova

Cases of pertussis, also known as whooping cough, rose in Uzbekistan towards the end of last year, notably among the adult population.

Uzbek media reported an increase in the number of cases of the bacterial infections in September 2023.

"My older child received all the vaccinations, but the doctors told the youngest daughter to postpone the vaccinations because the child was born weak. At seven months old, my daughter fell ill with whooping cough. My whole life flew by before my eyes while the baby was sick."

– Sabina Majidova, mother of two

Allaying worries, the Ministry of Health reported the epidemiological situation in Uzbekistan was stable, but emphasised the importance of vaccination against pertussis, urging individuals to ensure that they are up to date with their vaccinations.

Still, Uzbeks online have expressed concern that growing cases among adults could bode poorly for more vulnerable groups, like young children and elderly individuals.

Pertussis: the "100-Day Cough"

Until vaccination gained ground in the 20th century, pertussis was a major cause of childhood deaths worldwide.

The causative bacterium, Bordetella pertussis, releases toxins that damage the hair-like cilia on cells that line the upper respiratory tract, which makes the airways swell. In older children and adults, that causes coughing fits, often accompanied by a "whooping" sound on the effortful intake of breath.

The risk is highest in babies, who often don't cough, but stop breathing for periods of time, turn blue, and can suffer seizures and brain damage from oxygen deprivation. Still today, an estimated 160,000 children worldwide, most of them younger than one year, are killed each year by pertussis.

In wealthier countries including the US, waning immunity from the childhood jab has meant that pertussis rates have risen in older populations. That's a problem, not least because adults act as a reservoir for the bacterium, spreading it to vulnerable kids. Many countries recommend receiving a booster every ten years.

High immunisation rates

The vast majority of Uzbekistan is immunised against the infection. According to WHO, in Uzbekistan, 96% to 99% of eligible children have received three doses of the combined vaccine against diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis (DTP-3, now included in the pentavalent jab) every year since 2000.

The country's Ministry of Health has reported that in 2023, about 2 million children received the vaccine against the disease. Some 97.6% of targeted children were reached with the first dose of the pentavalent disease, known as Penta-1, 98.5% with Penta-2, and 98.5% with Penta-3 were vaccinated in the first eight months of last year.

But despite efforts to increase vaccination rates, there is still a need to address gaps in coverage and ensure that individuals across all age groups are adequately protected against pertussis.

Waning adult immunity, improved surveillance, may drive rising figures

To gain insight into the factors contributing to the increase in whooping cough, VaccinesWork reached out to the Ministry of Health for their perspective on the situation. A Ministry spokesperson highlighted several factors that may be driving the rise in pertussis cases, including waning immunity among adults, gaps in vaccination coverage and increased awareness leading to improved case reporting.

Have you read?

The Ministry is working to reduce and curb the spread of pertussis through a multi-faceted approach. This includes strengthening vaccination programmes, raising awareness about the importance of immunisation, and enhancing surveillance and response systems to detect and manage cases effectively. Additionally, efforts are underway to improve access to vaccination services and ensure that high-risk groups receive timely and appropriate protection against pertussis.

Falling through the cracks

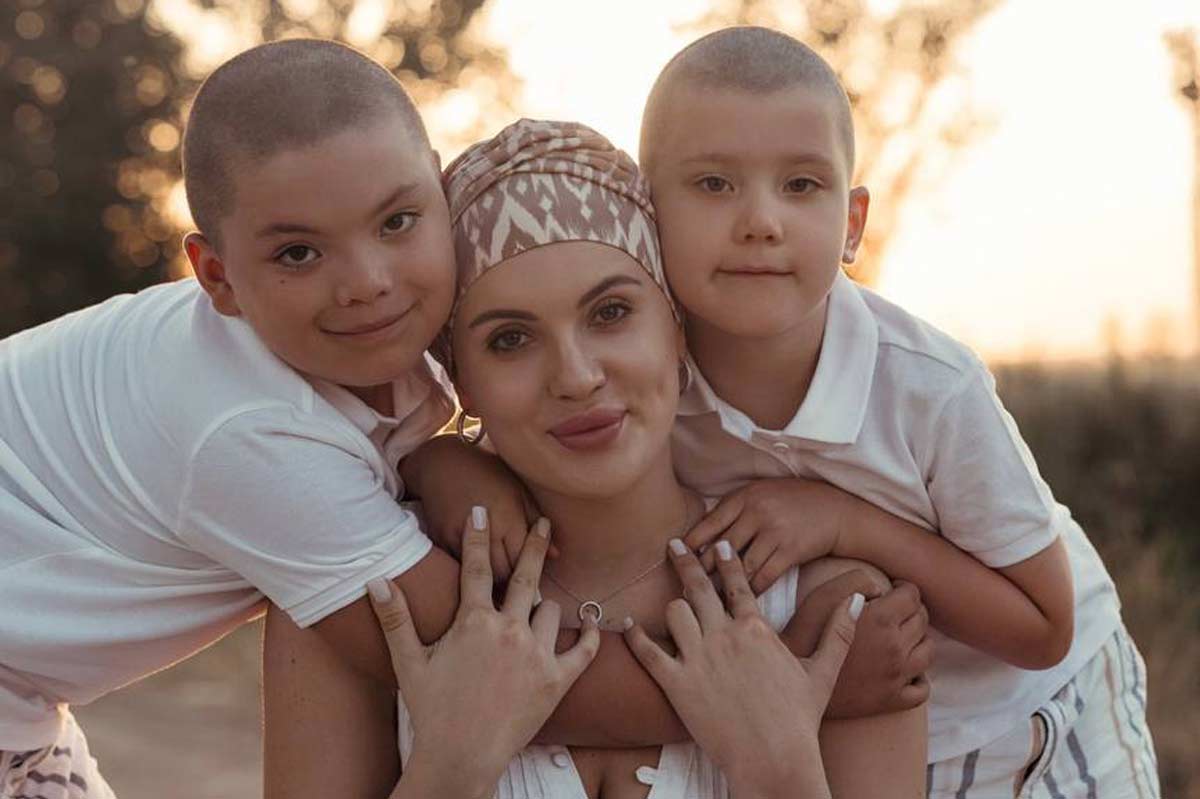

That's because even in a society with vaccination rates as high as Uzbekistan's, unvaccinated individuals remain in danger. Sabina Majidova knows that from bitter experience.

"My older child received all the vaccinations, but the doctors told the youngest daughter to postpone the vaccinations because the child was born weak," Majidova told VaccinesWork.

"My daughter is now nine months old and we have not received the DTP vaccine. At seven months old, my daughter fell ill with whooping cough. My whole life flew by before my eyes while the baby was sick. When your child is choking, and his mouth is full of drool and you can't do anything – babies don't know how to cough up – this is very scary. We were in the hospital, and they did a PCR test, which confirmed whooping cough. In addition, we received consultations from two pulmonologists, two paediatricians, and an infectious disease specialist. It's scary," she said, adding that while her DTP-vaccinated first-born child also contracted the illness, his symptoms were very mild.

"If a doctor gives a medical exemption (usually not longer than a month or two or three), treat the child and then immediately vaccinate them. Often, after receiving a medical exemption, parents and children disappear somewhere, and no one returns to get vaccinated. And this is the main mistake."

– Dr Bakhtiyor Begmatov, physician

Bakhtiyor Begmatov, an infectious diseases doctor from Tashkent, confirmed in an interview with local media that the city was seeing a significant spike in whooping cough cases.

"The problem is that people have stopped believing in the whooping cough vaccine and have become less likely to get vaccinated. That's why there is currently a lot of whooping cough in the city; a real outbreak," the doctor said.

According to Begmatov, many people seek treatment for whooping cough in private clinics with private paediatricians. "Private paediatricians often don't know how to treat whooping cough. That's why it's necessary to seek help from infectious disease specialists. Whooping cough should not be treated in private hospitals. This leads to even greater spread of the disease," the doctor said.

"For preventive purposes, it's necessary to get vaccinated on time. If a doctor gives a medical exemption (usually not longer than a month or two or three), treat the child and then immediately vaccinate them. Often, after receiving a medical exemption, parents and children disappear somewhere, and no one returns to get vaccinated. And this is the main mistake. A medical exemption is given for a specific period: you need to get treated, and then definitely get vaccinated," Begmatov noted.

Closing the cracks

The Ministry of Health noted that it is natural for whooping cough to be observed among the population, albeit in small numbers. "This disease can only be defeated by building collective immunity. To do this, it is necessary to vaccinate young children following the National Vaccination Calendar," the Ministry of Health said.

Meantime, the Ministry is pushing vaccination, surveillance, and public awareness initiatives to close immunity gaps and protect the population from this potentially serious illness.

More from Umida Maniyazova

Recommended for you