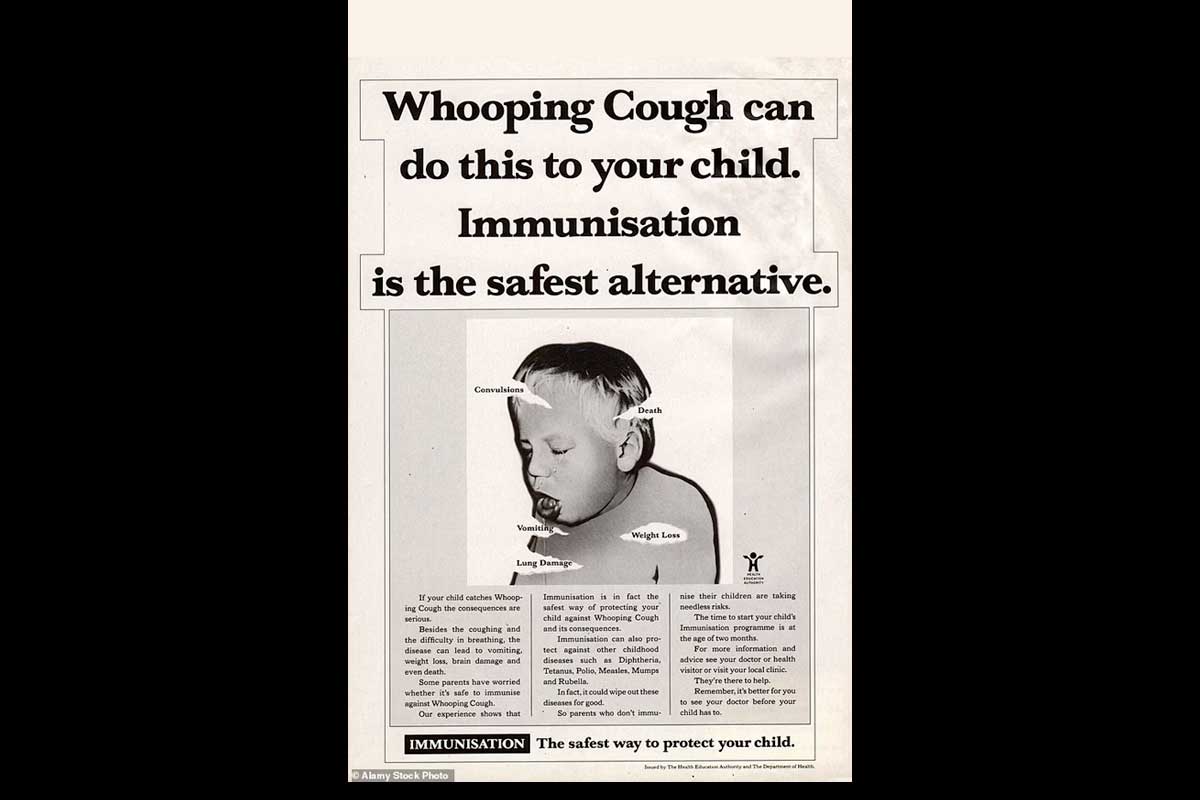

Reaching zero-dose children in Rajasthan

9.7 million children in 57 Gavi-supported countries remain unvaccinated and at risk. Why are these children missing out? In Bikaner, Rajasthan, VaccinesWork meets two families who simply never landed on the health system’s radar.

- 27 April 2021

- 6 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

Unlike most Indian babies, Morkhi’s son Dev was born at home. Morkhi was twenty-seven then, a daily wage labourer like her husband Ramesh and a first-time mother. She and Dev were both healthy after the birth and she continued to stay at home through his first days, puzzling out the early challenges of parenthood without the guidance of doctors or midwives. There may have been an Anganwadi – a government childcare centre that often acts as a node for basic healthcare provision – in easy reach, but Morkhi either didn’t know it, or never felt the need to visit.

Credit: Benedikt V. Loebell

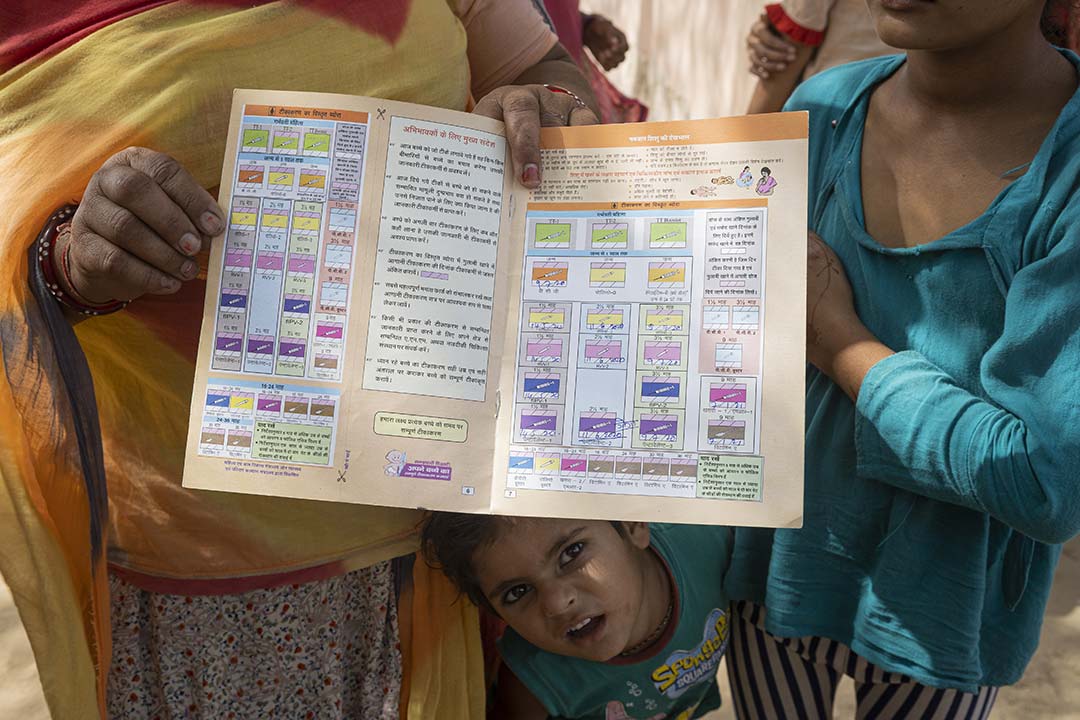

Three years passed. Now, Dev, Morkhi and Ramesh live in Khawaja Colony, a ramshackle community of migrant workers built on a railway track that slices through the desert city of Bikaner, Rajasthan. Dev is a stormy-faced boy, watchful under a thatch of black hair; a child of assertive personal presence. But from the perspective of the health system, Dev is as good as invisible: he has no birth certificate, and consequently, no “Mamta Card” to log his developmental milestones or keep him on track for routine medical care. In fact, Dev numbers among the nearly 10 million “zero-dose children” living in lower-income countries today. These are kids who have never received the protection of even a single vaccination.

Credit: Benedikt V. Loebell

As a zero-dose child Dev is at risk of being struck down by a disease like measles, diphtheria or polio. As many as half of the children who die of a vaccine-preventable illness in the 57 countries supported by Gavi are, like Dev, “zero-dose”, though unvaccinated children make up only an eighth of the birth cohort. And, although India’s national immunisation programme vaccinates an unmatched number of children annually, managing to cover 85% of its colossal population, the country remains home to 2.6 million unimmunised and at-risk kids1.

Credit: Benedikt V. Loebell

But how do you find the children who fall through cracks? That’s where SEWA come in. A fifty-year-old trade union of 1.5 million low-income, self-employed women workers from across India’s vast informal economy, they are now taking a particular interest in finding under-vaccinated children and, in the words of Dr Sahil Hebbar, who leads SEWA’s health programmes: “bringing them into the fold.” In doing so, they join a wider project. During the past half decade, through a diversity of initiatives, India has managed to trace and reach a staggering 40 percent of its unimmunised children.

Have you read?

SEWA takes a locally sensitive approach that focuses on bolstering members’ self-reliance, Rehana Riyawala, SEWA’s Vice President says. “For our workers, health is their wealth. It’s all quite interconnected, interrelated, with livelihoods.”

In a new push to make sure that no children are left behind, Gavi is targeting a 25% reduction in the number of zero-dose children living in the world’s lower-income countries by 2025. In all countries, local partnerships will prove vital to that goal. Homero Hernandez, who heads Gavi’s India country programme, says, “SEWA’s level of connection and embeddedness at the grassroots level – the trust that they have within the community – is critical.”

Credit: Benedikt V. Loebell

A network of “SEWA health ambassadors” or “SHAs” – women of standing in their communities, trained up on questions of public health by Dr Hebbar and colleagues – have discovered no fewer than 500 zero-dose children across 18 districts of five states during the last year. Though each case is individual, there are discernible patterns. In Bikaner, as elsewhere, gender is frequently an issue. In families with stretched resources, a son may be immunised while a daughter remains unprotected, says Dr Hebbar. Conversely, in communities where vaccine misinformation has gained a foothold, SEWA has found that a sister may be immunised while her brother is “spared” the perceived risk.

Credit: Benedikt V. Loebell

Dev’s case is typical of a different type, explains Asha Nainwal, a veteran SEWA organiser in Rajasthan. Migrants like Morkhi and Ramesh, who came to Bikaner from elsewhere in Rajasthan in search of work, often lack the documentation that would place them on the radar of health facilities. By the time Dev was born, Morkhi had missed out on the two shots of tetanus toxoid vaccine that India recommends for pregnant women. Dev’s home birth was another missed intersection with the organs of public health.

SEWA helps build the remedial link but, particularly in rural areas, where families might be beyond reach of healthcare facilities, this can be a halting process.

|

|

Credit: Benedikt V. Loebell

On a recent sun-baked Saturday, SEWA organisers visited a village south of Bikaner, and met with a quiet thirty-year-old mother of five named Sushila, whose husband herds cattle for a living. All of Sushila’s children were home-born, and all are unvaccinated. A neighbour named Laddodevi, who described Sushila as “like a daughter” to her, gestured to Sushila’s young son: “Chhotu had vomiting for a year! One could take them to a children’s hospital in Bikaner and get medicines. But who would take them there? Her husband is away all day, minding the cows as they graze.”

For people on the fringes, the bureaucracy of identity can be a labyrinthine business. Sushila’s own efforts to secure rations and healthcare have ended in frustration: “there is no trust remaining,” she said.

|

|

Credit: Benedikt V. Loebell

“Most of the time it takes repeated meetings and conversations for building trust,” says SEWA’s Nainwal. Listening to women, learning about their difficulties, and helping resolve them seeds confidence, she says. But bringing a missed family into the fold can “take a certain time, as it needs to be done with the government agencies”. Sushila’s case is being pursued, but now that COVID-19 case numbers are exploding across India, necessary meetings may need to wait.

Back in Khawaja Colony, on the edge of the railway tracks, things seem to be moving more quickly. SEWA health ambassadors learned that Morkhi’s mother-in-law was hesitant to have Dev vaccinated, having developed a misplaced fear of fatal side-effects. The local SHAs sat with Morkhi and explained the mechanisms of vaccination; that post-jab fevers were short lived and easily alleviated with paracetamol. Morkhi listened, and ultimately chose to accept their offers of help to get hold of a Mamta Card. In a recent email update, Nainwal and Riyawala wrote, “Morkhiben has assured that she will be getting her son vaccinated.”

More from Maya Prabhu

Recommended for you