Six major health threats that could shape 2026: here’s what experts are watching

A new Gavi insight paper highlights six immediate threats to global and regional health in 2026, and some of the initiatives, tools and solutions designed to keep them at bay.

- 19 February 2026

- 12 min read

- by Linda Geddes

These are challenging times for global health. From conflict-related disease outbreaks and rising health misinformation to climate change and global health funding cuts, the risks to our collective global health are growing, and can feel overwhelming.

Yet, even as these risks intensify, global health organisations and their partners are mobilising research, resources and new tools to bolster our defences against these global health threats.

A new insight paper published by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, examines six immediate threats to global and regional health in 2026, why they matter, and the initiatives and solutions aimed at keeping us all safe.

1. Conflict-associated outbreaks

By some measures, violence and disputes between and within states are approaching their highest levels since World War II. Conflict drives the emergence and transmission of infectious disease by displacing populations, disrupting healthcare delivery and breaking supply chains for food, clean water and medicines. It can also accelerate the spread of antimicrobial resistance.

The degree to which conflict helps to drive disease outbreaks depends on local conditions, says Carrie Nielsen, immunisation lead at the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. “A lot of factors contribute, including environmental conditions, the ability to deliver health services during the conflict, and pre-conflict health infrastructure and immunisation coverage.”

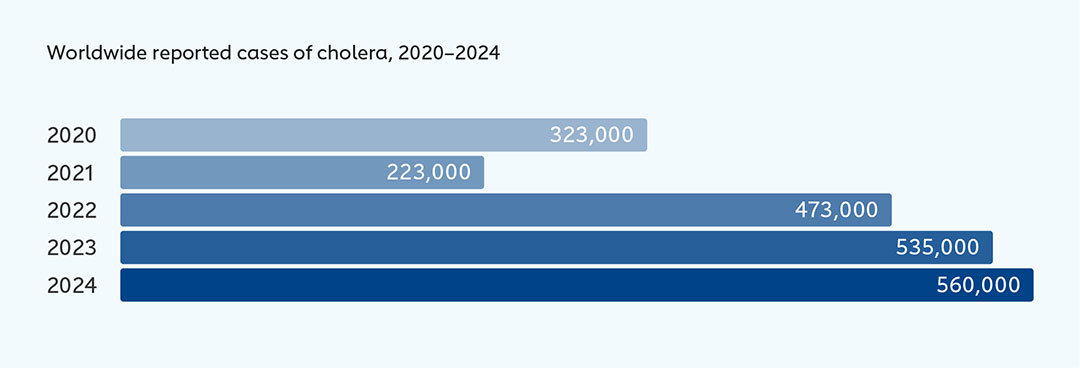

Cholera illustrates how conflict-related conditions can accelerate disease spread. More than 6,000 people died from the disease in 2024 – around 50% more than in 2023 – while the number of affected countries rose from 45 to 60. The current surge has been worsened by disruptions to surveillance and response in conflict-affected areas including parts of Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Although multiple factors are driving the upsurge, safe water, sanitation and effective case management remain essential for outbreak control. “In areas affected by conflict, when people are being displaced, it can be difficult to provide basic services and prevent the disease spreading,” says Allyson Russell of Gavi’s Outbreaks and Global Health Security team.

Despite these challenges, efforts to prevent and control outbreaks are expanding. Global production of oral cholera vaccine has increased from around 30 million doses in 2022 to 80 million in 2025, supported by manufacturers, donors and Gavi’s expanded investment in cholera prevention and response – including support for the global oral cholera stockpile.

Looking ahead, Gavi is increasing its support for populations in conflict and other fragile settings by more than 15% during 2026–2030 compared to the previous five-year period including introducing a new agile funding tool – the Gavi Resilience Mechanism (GRM) – designed to respond rapidly to unexpected health emergencies and humanitarian crises that are not covered through existing mechanisms.

2. Climate change and arboviruses

Climate change is reshaping the geography of diseases caused by arboviruses – those spread by mosquitoes and other arthropods.

Although the relationships between these viruses and climate are complex, a growing body of research shows that rising temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns and more frequent flooding are expanding mosquito habitats. “This is leading to more outbreaks of diseases including malaria, yellow fever, chikungunya and dengue,” says Ignacio Esteban, Senior Manager in Gavi’s Policy team.

When researchers from Imperial College London and the World Health Organization (WHO) modelled yellow fever cases in Africa, for example, they found that deaths could increase by 11–25% by 2050.

A separate study found that the global population at risk of mosquito-borne diseases will increase by around half a billion, to 6.5 billion by 2050. Updated risk maps published in 2025 also show dengue, chikungunya, Zika and yellow fever expanding into higher latitudes, including parts of Mexico, Europe and the Middle East.

Temperature is a key driver. Mosquitoes – especially Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus – are the primary vectors for dengue, Zika and chikungunya. “When temperatures rise, mosquitoes become adults more quickly, and the incubation period of the viruses within mosquitoes is shorter, which increases the speed of transmission of these viruses to humans,” says infectious disease epidemiologist Diana P. Rojas, of the WHO Global Arbovirus Programme and co-lead of the Global Arbovirus Initiative.

Record heat is already translating into record disease. In 2024 – the warmest year on record – more than 14.4 million dengue cases were reported globally, more than double the previous peak in 2023.

Extreme weather is compounding the risk. Scientists warn that floods, droughts and heavy rains can increase human exposure to mosquitoes and other vectors. “After a rainy season, when there are floods or when people collect water because of drought, there will be more breeding sites for mosquitoes, and then those places are more likely to have dengue or other arbovirus outbreaks,” says Dr Rojas.

Have you read?

The burden falls disproportionately on lower-income countries and vulnerable groups, including children, women and displaced populations.

In response, global efforts are to address this threat are expanding. WHO’s Global Arbovirus Initiative aims to strengthen surveillance, preparedness and vector control, while the World Mosquito Program is releasing mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia bacteria to reduce their ability to transmit viruses. Gavi is also planning to invest US$ 2.2 billion in vaccines against climate-sensitive diseases, including cholera, Japanese encephalitis, malaria, meningitis A, typhoid and yellow fever.

3. Global health funding cuts

Sharp reductions in aid from high-income countries to lower-income nations in 2025 have disrupted essential health services, from disease surveillance and vaccination to maternal care and emergency preparedness.

The scale of the cuts is already threatening hard-won health gains across low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), and the full impact will become clearer in 2026 as countries try to mobilise alternative funding.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) projects that official development assistance (ODA) – government aid intended to promote economic development and welfare in LMICs – will fall 9-17% in 2025, after a 9% drop in 2024. WHO also warns that external health aid could be 30–40% lower in 2025 than in 2023, placing immediate pressure on essential health services.

WHO survey data from 108 LMICs indicates that funding cuts have already reduced critical health services by up to 70% in some countries, with job losses among health workers and disruptions to training. These pressures come on top of inflation, economic uncertainty, constrained national budgets and rising debt burdens.

Whether these funding gaps can be partially filled through bilateral and domestic funding remains unclear, but early evidence suggests that weakened systems may be undermining countries’ ability to prevent and respond to outbreaks.

As part of the Gavi Leap initiative, vaccine financing will be simplified to give countries more flexibility in how they run immunisation programmes. Gavi is also working with multilateral development banks to expand sustainable financing for health and immunisation.

In October 2025, a GiveWell assessment of immunisation programmes in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Madagascar and Nigeria highlighted losses of community health workers, unreliable vaccine delivery, stock-outs, cancelled sessions and declining coverage, particularly in rural areas. Progress in reaching ‘zero-dose’ children is reversing, and data systems are deteriorating.

In response, global health organisations are exploring new approaches. As part of the Gavi Leap initiative, vaccine financing will be simplified to give countries more flexibility in how they run immunisation programmes. Gavi is also working with multilateral development banks to expand sustainable financing for health and immunisation.

Meanwhile, The WHO-led 3 by 35 Initiative calls for increases to the prices of tobacco, alcohol and sugary drinks by at least 50% by 2035 through taxation, to help establish sustainable, domestically sourced financing as ODA falls.

4. Health misinformation

Health misinformation is becoming one of the most destabilising forces in global health.

It erodes trust, shapes behaviour and weakens health systems at a time when vaccine-preventable diseases such as measles are resurging, and the risk of another pandemic remains. As 2026 begins, a central question is whether health systems have the capacity to respond to this growing threat.

Global risk assessments increasingly reflect this concern. Both the UN Global Risk Report 2024 and the World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2026 rank mis- and disinformation among the most severe global threats.

Vaccines offer a clear example of the damage misinformation can cause. When confidence declines, preventable diseases return and trust in institutions fractures further.

Nigeria’s advertising regulator has warned that AI-generated adverts using cloned images and voices of trusted religious and media figures are circulating on social media to promote fake medical cures.

Common false claims focus on safety, including infertility, toxic ingredients and severe side-effects, often reinforced by historical grievances, inequitable access and religious misconceptions. During the 2024 mpox outbreak in Niger, for instance, social media posts accused international organisations of spreading the virus and distributing harmful vaccines.

What makes 2026 different is not the novelty of these claims, but the environment in which they increasingly circulate. The 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer Special Report: Trust and Health found that one in three young adults worldwide feels uncertain about childhood vaccines and relies more on social media and personal experience than on doctors or scientific evidence.

AI is accelerating the problem. The growing use of deepfakes in health disinformation shows how quickly false narratives can now be created and spread. In July 2025, for example, a fake video circulated on Facebook purporting to show a WHO press conference in which a spokeswoman falsely claimed that a proposed pandemic treaty would remove human rights protections and impose mass surveillance and censorship.

Meanwhile, Nigeria’s advertising regulator has warned that AI-generated adverts using cloned images and voices of trusted religious and media figures are circulating on social media to promote fake medical cures.

However, efforts to respond are expanding. WHO’s Africa Infodemic Response Alliance tracks misinformation trends and keeps infodemic managers, communicators and public health professionals informed about the main ones circulating in the region, while Gavi and WHO are increasingly working with tech companies such as Google and Meta to promote reliable information online.

Gavi also invests in programmes to train, and support health workers so they can better meet community needs for vaccination, and help countries anticipate and respond to rumours or misinformation around vaccines. Still, tackling health misinformation will require sustained, cross-sector action well beyond the health sector alone.

5. Marburg virus disease

Marburg virus disease is unlikely to cause the next global epidemic, but in 2026 it remains a growing regional threat in parts of Africa.

It also illustrates how ecological disruption can increase the risk of rare but deadly pathogens spilling over into humans, with the heaviest toll in communities where health systems are weakest and access to care is delayed.

Experts say preparedness – especially early detection and resilient health systems – will determine whether future cases remain contained or escalate.

Marburg virus is a filovirus, related to Ebola, and spreads mainly through contact with bodily fluids. It causes severe illness marked by high fever, muscle pain, gastrointestinal symptoms and, in some cases, internal and external bleeding. Case fatality rates often exceed 50%, particularly where diagnosis and supportive care are delayed.

“Marburg virus disease is not a global threat per se, based on current understanding of the virus,” says Anaïs Legand, Technical Officer for Viral Haemorrhagic Fevers at WHO. However, outbreaks can still have severe economic and social impacts in affected countries.

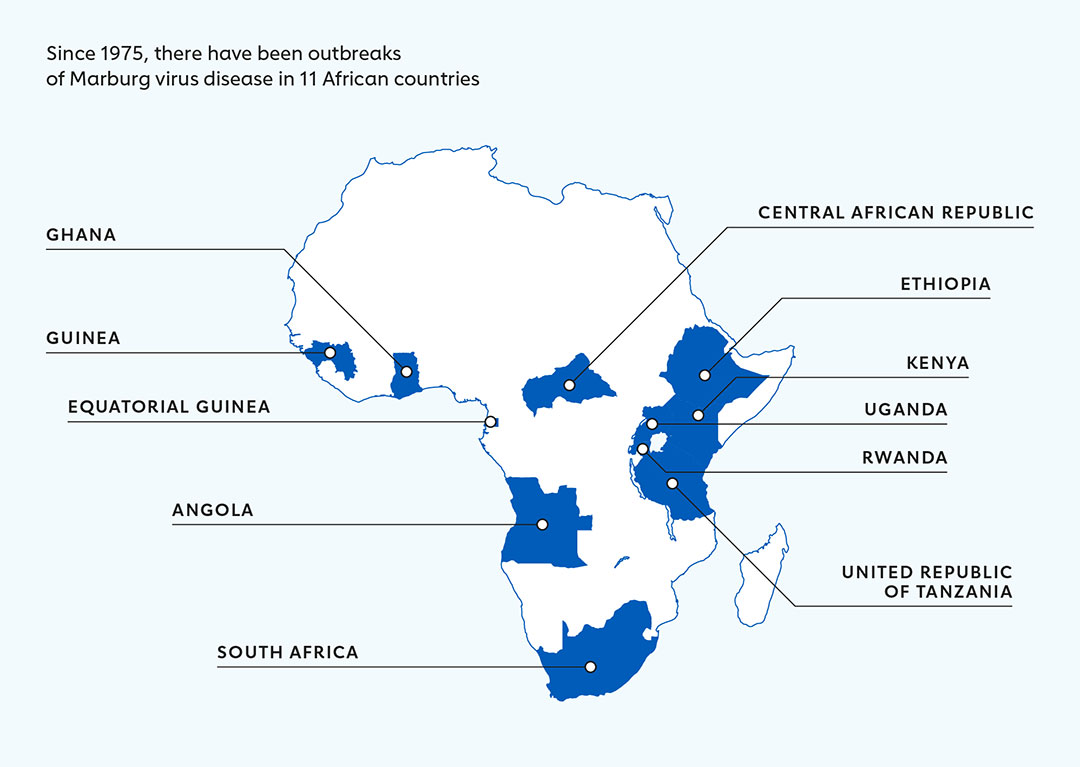

Recent years have seen Marburg detected in more countries, including Guinea, Ghana, Tanzania, Equatorial Guinea, Rwanda and Ethiopia. While improved surveillance may partly explain this, ecological pressures are also likely contributing.

The virus’s natural reservoir, Egyptian rousette fruit bats, is widely distributed across East, Central and West Africa. As deforestation, land-use change and expanding human activity bring people into closer contact with bats, spillover risk rises. Reducing exposure and strengthening detection – rather than harming bat populations, which play vital ecological roles – are key prevention strategies.

Marburg has not yet caused a large-scale epidemic, but Ebola’s history shows how filoviruses can devastate fragile health systems. Marburg is thought to be slightly less transmissible, yet an undetected outbreak in a densely populated area could still escalate rapidly.

“The worry is that right now, we don’t have sufficient data to understand exactly which are the places at risk in every country with Rousettus bat presence, limiting ability to reduce bat-to-human exposure and prevent spillover events,” says Legand.

With fewer than 800 confirmed human cases recorded since 1967, Marburg does not justify major standalone investments. Instead, preparedness must be embedded in broader health system strengthening – from surveillance and laboratory capacity to infection prevention and control, and community trust – which also improves responses to other infectious threats.

Trials of promising vaccine candidates and potential treatments are underway, while WHO, Africa CDC and partners are investing in research, diagnostics and outbreak response capacity to improve detection and response.

6. Disease X

When global health experts refer to Disease X, they are not predicting a specific virus or date. The term describes the next unknown pathogen with the potential to spark a serious international epidemic or pandemic. While 2026 is not inherently more dangerous than other years, several assessments suggest the world may be entering it less prepared than in the immediate aftermath of COVID-19.

COVID-19 itself was a Disease X event: a novel coronavirus that spread rapidly and exposed weaknesses in surveillance, preparedness and response. This century has already seen an influenza pandemic (H1N1 in 2009), alongside major epidemics caused by SARS, MERS, Ebola virus disease, mpox and Zika.

Scientists believe the next major threat is most likely to emerge from one of roughly 25 viral families already known to infect humans.

While 2026 is not inherently more dangerous than other years, several assessments suggest the world may be entering it less prepared than in the immediate aftermath of COVID-19.

Influenza viruses remain a key concern. While H5N1 avian influenza is closely watched, Dr Maria Van Kerkhove, interim Director of WHO’s Department of Epidemic and Pandemic Management, warns of the risk posed by zoonotic influenza more broadly – where animal influenza viruses occasionally infect people and could evolve into strains capable of sustained human transmission.

In rare cases, influenza viruses can exchange genetic material through reassortment, producing a strain to which humans have little or no immunity. “The possibility of such a reassortment sparking the next pandemic is strong,” she says.

Other high-priority threats include coronaviruses, filoviruses such as Ebola, and mosquito-borne viruses like dengue. The risk lies not only in their emergence, but in delayed detection and response. A 2024 implementation review of the 100 Days Mission by the International Pandemic Preparedness Secretariat (IPPS) found that preparedness is uneven across pathogens, with diagnostics and therapeutics lagging far behind vaccines.

A 2025 Global Diagnostics Gap Assessment by IPPS echoed this finding, identifying diagnostics as the weakest link in pandemic preparedness, and urging sustained investment in adaptable testing platforms, regional evaluation centres and better-aligned regulatory processes.

Efforts to close these gaps are under way. WHO’s Strategic Plan for Coronavirus Disease Threat Management promotes integrating surveillance for influenza, coronaviruses and other respiratory threats into routine health systems, using multi-pathogen platforms, genomic sequencing and wastewater monitoring.

CEPI’s 100 Days Mission aims to develop vaccines and diagnostics for a new threat within 100 days of its identification, including through prototype vaccines for high-risk virus families.

Still, experts warn that without sustained funding and political commitment, these systems may not be strong enough when Disease X emerges.