Vaccine subterfuge: How vaccine-makers fooled the Nazis from inside a concentration camp lab

Confined first at Auschwitz then Buchenwald, a Jewish microbiologist conspired with a ragtag team of scientists and rebels to send dud typhus vaccines to the German soldiers on the eastern front.

- 18 May 2022

- 10 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

A few days after the surviving soldiers of the ragged sixth German army surrendered their months-long, bloody offensive on Stalingrad in February 1943, conceding a major defeat for the Nazi imperial project in eastern Europe, a Jewish scientist called Ludwik Fleck, his family, and some of his colleagues, were shuffled onto a passenger train in Lwów in Nazi-occupied Poland and transported to Auschwitz. There, they were processed – probably stripped, shaven, and showered – and assigned to barracks at the main camp. A ledger recorded Fleck’s admission in pencil: prisoner number 100967.

"We made a vaccine that did not work. For controls we sent a sample that did work. Ding-Schuler, the illiterate, didn’t realize what was going on." The good vaccine was administered to vulnerable people in the camp for their protection.

In fact, this new camp inmate was not as anonymous – nor, for that matter, quite as easily expunged – as his ledger entry implied. The German war effort was under pressure not only from enemy fire and the brutal Russian winter, but also from epidemic disease. Fleck, a microbiologist who in 1942 had managed to design a novel typhus vaccine in a poorly-equipped lab in the deprived conditions of the Lwów ghetto, was a resource the Nazi command intended to squeeze.

General Typhus, Warmonger

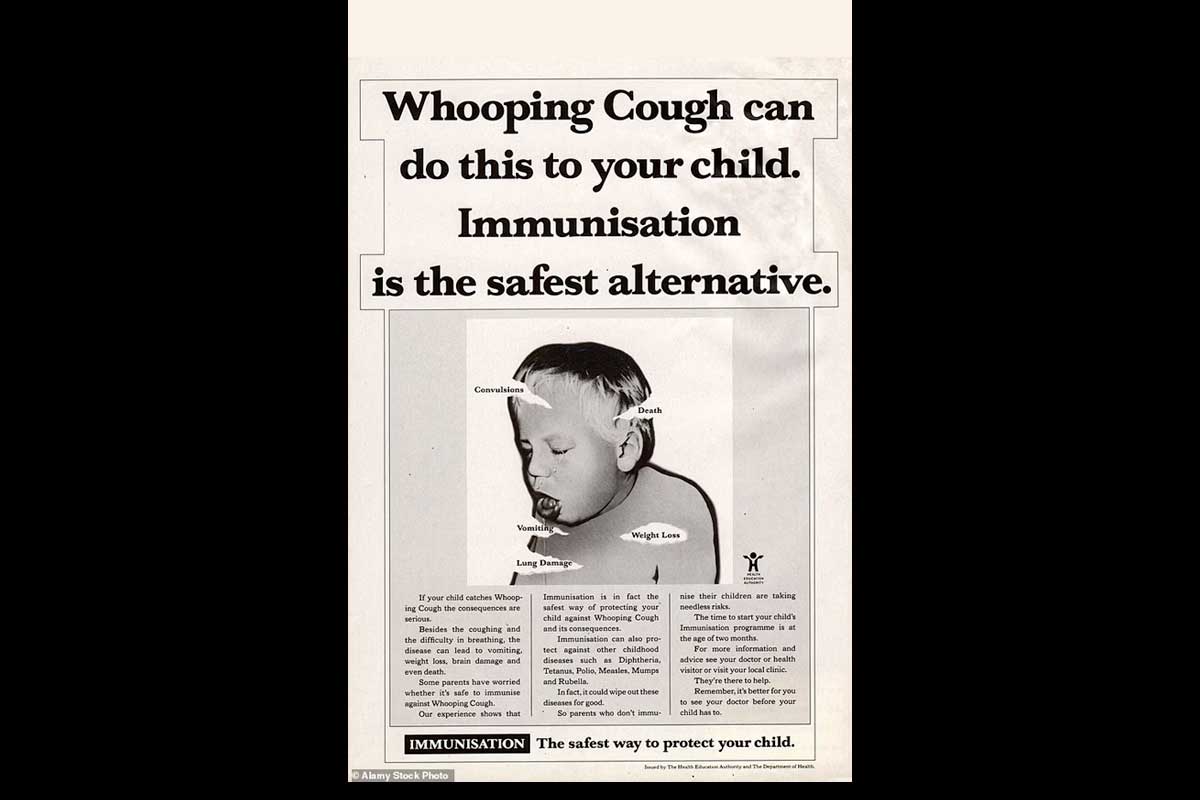

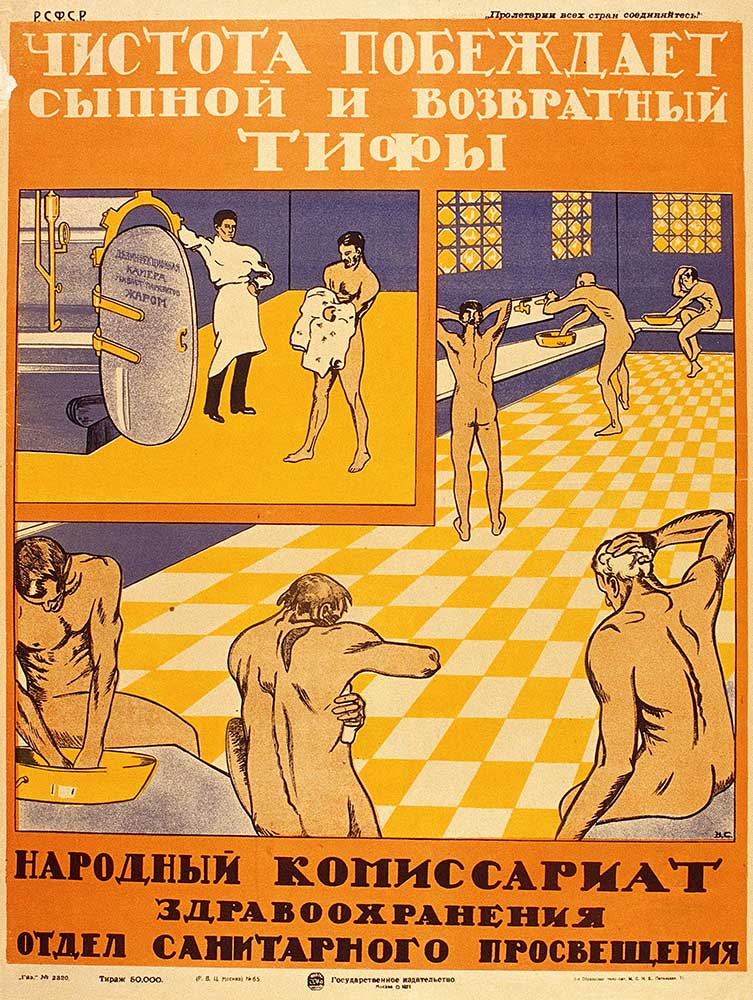

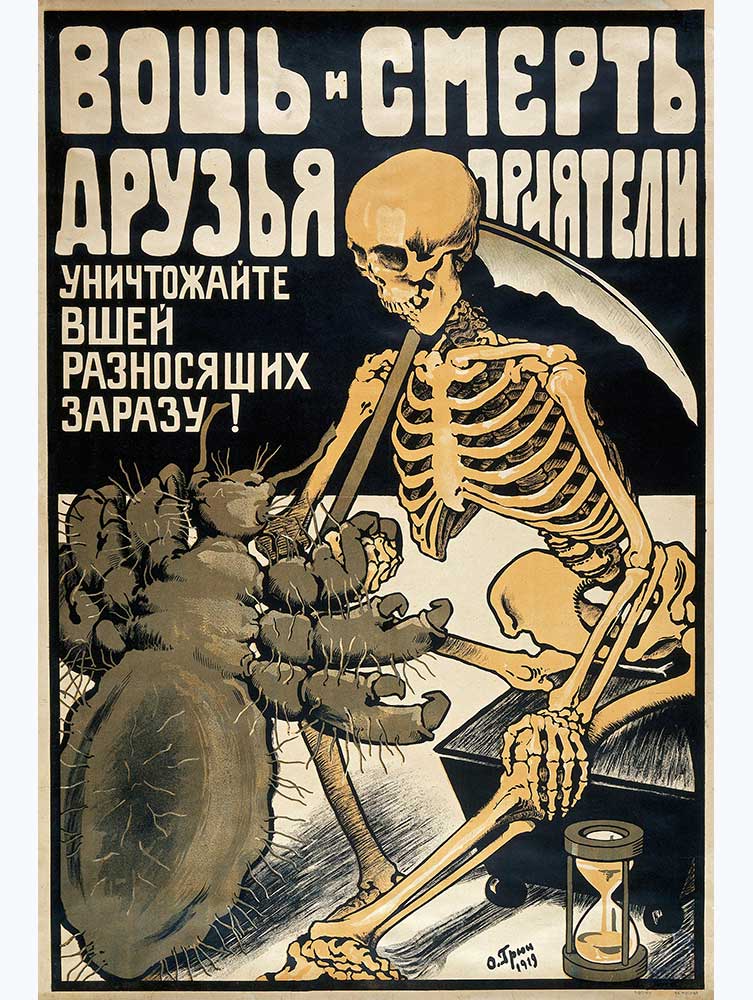

Typhus, a louse-borne epidemic disease caused by the bacterium Rickettsia prowazekii, was a source of wartime worry for good reason. Lice thrived in the crowded, unsanitary conditions conflict tended to produce; typhus thrived in bodies weakened by stress and malnourishment.

Symptoms included high fevers and rashes, pain and psychosis. “Typhus epidemics occur when a population is at the end of its tether,” writes journalist Arthur Allen in his book The Fantastic Laboratory of Dr. Weigl1. Outbreaks were common in the trenches of war and in the settlements of the persecuted, and each flare of disease risked leaving between five and 40 percent of its victims dead.

Alive in the memory of many during this new, consuming European war was the last great epidemic, which rode the wake of the last great conflagration. World War One’s frontlines had been dogged by infection – some 150,000 Serbian troops died of typhus just in 1915. Between 1918 and 1922 typhus sped across Russia and Poland, infecting some 30-40 million, killing maybe three million.

Credit: Wellcome Collection. In copyright |

Credit: Wellcome Collection. In copyright |

But since then, several dedicated and inventive researchers had taken up the typhus challenge – and it was a significant challenge, as R. prowazekii was exceptionally difficult to grow in a lab. They made potentially transformative progress.

The vaccines exist…

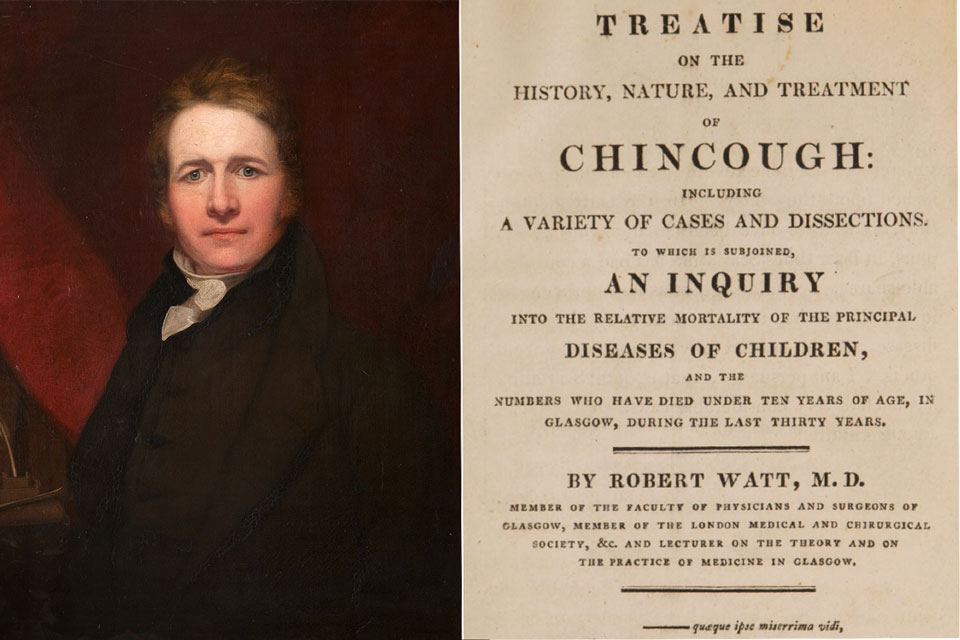

In the 1920s, a Lwów zoologist called Dr Rudolf Weigl – who had worked out how to anally inoculate lice with the typhus germ and how to extract the R. prowazekii-riddled louse-guts at some speed – was able to produce enough usable killed typhus antigen to constitute the first functional typhus vaccine. In 1928, two Pasteur Institute scientists in Tunis tested Weigl’s vaccine successfully on humans.

Through the 1930s, scientific interest in the typhus vaccine grew. Late in that decade, the American Harald Cox discovered a method for inoculating the yolk sac of chicken eggs with the typhus germ to produce the antigen and, from that, a vaccine. In 1940, French scientist Paul Giroud and colleagues Michel Durand and Helena Sparrow collaborated to create a vaccine grown in the lungs of immune-compromised small mammals, which would enter large-scale production in Vichy France within a couple of years.

In 1942, Dr Ludwik Fleck, who had joined the Weigl lab as Weigl’s assistant in 1919 but had gravitated towards philosophical investigations into the nature of scientific knowledge during the 1920s, developed a radically different production approach.

By now, Lwów was under Nazi occupation and Fleck was captive in the walled-in Jewish ghetto. Typhus raged, infecting nearly 100% of the ghetto population, and killing 30%. Medical supplies ran low, then ran out. Ghetto hospital colleagues disappeared in raids.

There was no way to create a functional Weigl-style louse-lab in these conditions2. But with such a vast supply of infected people, Fleck began to search for the typhus antigen in human sources – specifically, in the urine of the sick. He found it, deriving first a diagnostic method, and then a vaccine. By August 1942, he would be ready to test the vaccine on himself. Eventually, some 500 ghetto inmates would be administered the Fleck jab.

… but vaccines do not necessarily equal vaccination

The news of Fleck’s vaccine travelled fast. Soon, the scientist was ordered to report to the local Gestapo HQ with his experimental blueprints. Uniformed medical specialists “wrote things down, repeated questions”, Fleck said, and “shouted at us and threatened us. Some of the questions were not very intelligent. For example, they asked if the vaccine would work for Aryans. I replied, ‘Of course, but it must be made from Aryan and not Jewish urine.’”3

Uniformed medical specialists “wrote things down, repeated questions”, Fleck said, and “shouted at us and threatened us. Some of the questions were not very intelligent. For example, they asked if the vaccine would work for Aryans. I replied, ‘Of course, but it must be made from Aryan and not Jewish urine.’”

Fleck’s remark was, of course, sarcastic – a barb at the race-obsessed pseudoscience that characterised the Nazi approach to public health. “Nazi ideology had identified typhus … as a disease characteristic of parasitic, subhuman people – the Jews,” Arthur Allen writes. That racial fixation may have cost the Germans the advantage on disease control – at war’s start, Allen notes, Germany trailed its neighbours on typhus research.

But regardless of the faulty logics animating the Nazi health establishment, by 1942 typhus had established itself as a pressing threat to German fortunes – a more actual one than the imaginary spectre of Jewish socio-pathological contamination. That year 40,000 typhus cases had been reported among the retreating German soldiers on the eastern front. More than 10% of them would die. Weigl’s lab had been conscripted into vaccine production for the Wehrmacht, and an Institute for Typhus and Virology at Krakow was also manufacturing vials of the stuff for the troops. But the vaccine was a logistical nightmare to produce, and the German army needed more doses than Lwów and Krakow could send.

Have you read?

Captive science

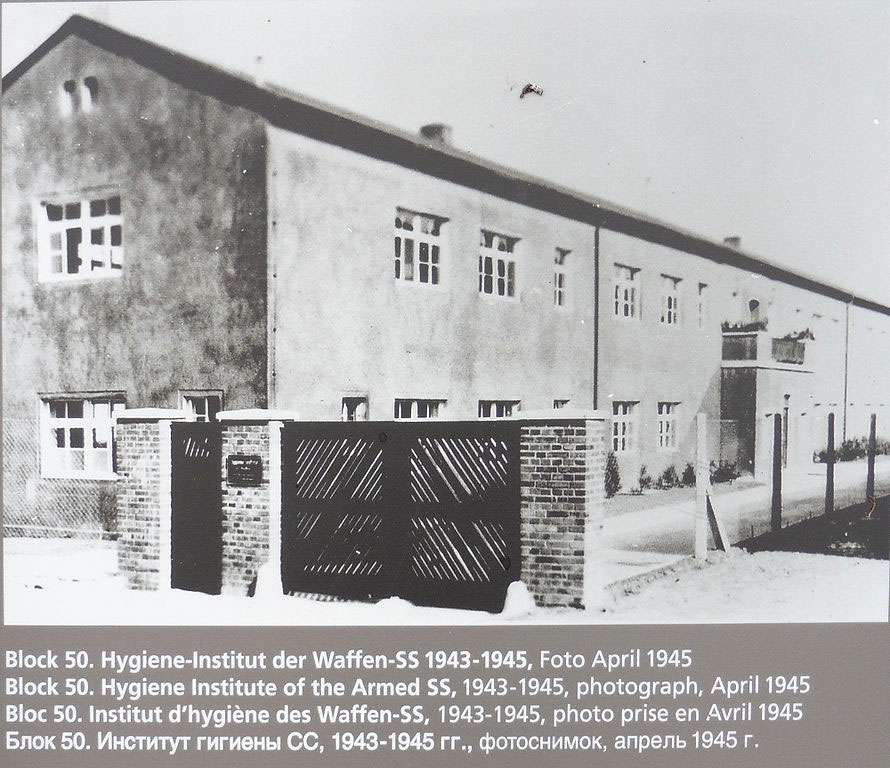

As Fleck and his laboratory colleagues were arriving at Auschwitz, Joachim Mrugowsky, head of the SS Hygiene Institute in Berlin, was incubating a plan to build a new typhus vaccine manufacturing hub at Buchenwald concentration camp near Weimar.

The facility opened in Block 50, a chunky, utilitarian three-storey building about half a mile from the camp entrance, in August 1943. Directed by a dozy, careerist SS doctor called Erwin Ding-Schuler, it was staffed by inmate slave-labour. Most of the prisoners on the team were scientists and physicians (one was a pastry chef pretending to be a doctor as a way of staying alive), but none of them was an immunologist. And none had experience in wrangling R. prowazekii, an elusive and changeable bug.

Instead, they were working like amateur cooks from a recipe book – a 70-page manual, translated into German from the French, describing the production of the Giroud-Durand vaccine, which was considered to be the most practical vaccine for the conditions at Block 50.

Put crudely, the procedure was to passage the bacterium through different animal species, subtly changing it so that the antigen would propagate well in rabbits, allowing for large-scale production. The starting germ sample came from Block 46, a grim experimental facility housing often artificially-infected typhus patients drawn from the imprisoned population.

Infected human blood was passed into guinea pigs, who, once sickened, were killed. Their brains and testes were then ground up and injected into mice, whose hopefully germ-rich lung-tissue was inoculated into rabbits. Normally not susceptible to R. prowazekii, the rabbits were subjected to stresses – cold temperatures, poor diets – in order to suppress their immune function.

As the Block 50 team doggedly trudged the steps of their vaccine manual that summer and autumn, Fleck was still at Auschwitz. After a month-and-a-half stint hauling corpses, the microbiologist was now working alongside his wife and former lab-mates conducting bacteriological research on inmate blood and urine samples.

But in December, around the time that the first samples from the Buchenwald lab were tested on subjects in Block 46 with poor results, a private car came for Fleck and drove him away from his wife and son, 600 kilometres west, to Block 50.

Credit: Heinrich Stürzl

Conspiracy

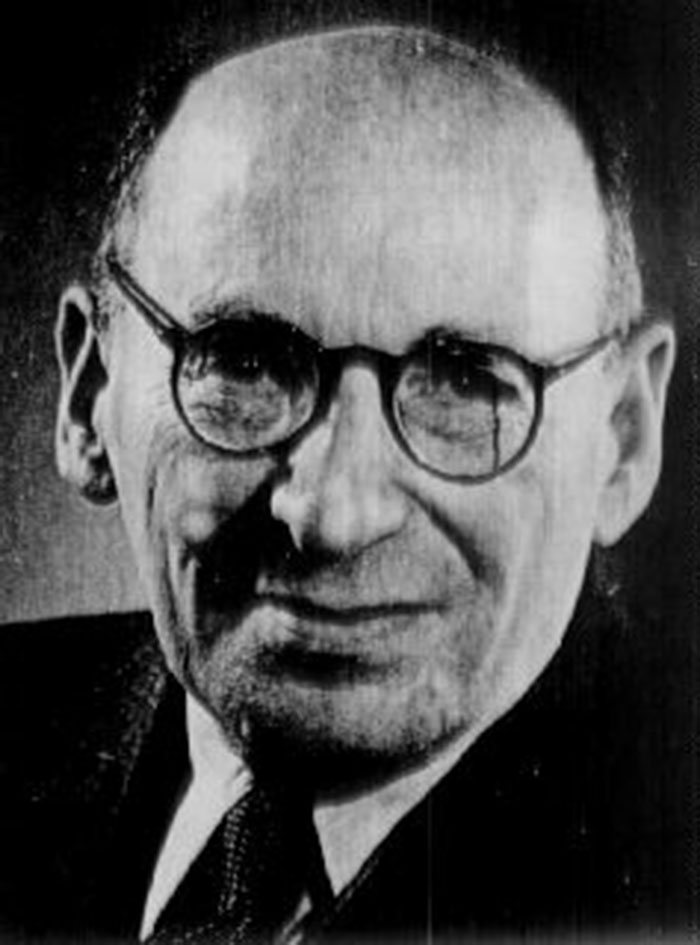

Camp inmate Eugen Kogon, a man observant and socially agile enough to become indispensable to his Nazi overlords even as he hatched schemes to undermine them and protect their victims, clocked the balding, bespectacled, middle-aged new arrival as a “somewhat dreamy scholar, always friendly”.3 At the Nuremberg Trials that succeeded the war’s end, Kogon would say that he had not considered Fleck the conspiratorial type.

Credit: Magnussen, Friedrich (1914-1987)

But Fleck immediately saw what neither the other inmates nor Ding-Schuler had been able to discern. The vials of so-called “vaccine” contained no antigen at all – the Block 50 jab was nonsense. What the team had understood to be typhus germs, had actually been rabbit white blood cells – harmless, useless.

Kogon recalled: “We asked [Fleck] not to say anything about what he’d seen to Ding-Schuler, but to experiment with us, to try to allow us to find a good way out of the difficulty. He worked with us, and he kept the secret.” When the team received infected mouse lung material from Krakow, they began, under Fleck’s guidance, to produce a real, “very efficacious” vaccine – but only in small quantities.

They continued, simultaneously, to produce and ship out what would amount to a total of 600 litres of false vaccine, enough to “fully vaccinate” – pointlessly – 200,000 soldiers. Fleck later testified: “We made a vaccine that did not work. For controls we sent a sample that did work. Ding-Schuler, the illiterate, didn’t realize what was going on.”3

The good vaccine, of which there would be only six litres, was not only submitted to the SS higher-ups for scientific double-checking, but also administered to vulnerable people in the camp for their protection. The discarded rabbit carcasses, meanwhile, were boiled secretly for stew, shared between the vaccine-makers, and doled out to other starving inmates.

The game is up

The team ran their immunological subterfuge for nearly year and a half, withholding, by stealth, their skills and labour from the faltering Nazi project, even as their incarceration at the labour camp appeared to strip them of their choice in the matter.

The stakes were brutally conspicuous. More than 250,000 people were imprisoned at Buchenwald between July 1937 and April 1945. Some of the most physically vulnerable, the skeletal inmates of the Little Camp, would have been visible, Allen notes, from the windows of Block 50.

By 1940, so many prisoners were dying each day at Buchenwald that the SS stopped being able to dispose of their bodies at the Weimar municipal crematorium, and built its own, more capacious facility. And still, when the Americans breached the gates of the camp on April 11 1945, unburnt, unburied corpses of Jews and Roma, gays, Communists, and other ‘enemies’ of Nazism, were stacked like hay bales here and there.

Photo taken by Jules Rouard – Belgium

By the time the Allied forces arrived, the camp administrators had fled, and the prisoners, many in terrible body condition, had stormed the guard towers. “I saw before me the walking dead,” said Leon Bass, a GI from Philadelphia.3

A little over two years later, Mrugowsky was on trial in Nuremberg. He boasted that the vaccine produced at Block 50 was the best in Germany – and was stunned to learn for the first time that it had been little more than a placebo.

1. Allen’s The Fantastic Laboratory of Dr. Weigl: How Two Brave Scientists Battled Typhus and Sabotaged the Nazis, traces the intersecting stories of the Polish gentile typhus vaccine inventor, Dr Rudolf Weigl, and of the influential Polish Jewish microbiologist and philosopher of science, Dr Ludwik Fleck. The present article is heavily indebted to Allen’s reporting. Interested readers are encouraged to also check out Allen’s Politico article on Fleck.

2. Around the same time, doctors working in similar conditions in the Warsaw ghetto managed – amazingly – to curtail a major typhus outbreak before its anticipated winter peak. Interested readers can find a 2020 research article on how that was achieved in Science.

3. Allen, The Fantastic Laboratory of Dr Weigl

More from Maya Prabhu

Recommended for you