EFFORTS TO REACH EVERY CHILD CALL FOR CHANGING THE COUNTRY’S NUMBERS CULTURE

Checking childrens’ birth dates and their last vaccinations are the first questions that Sister Sofia Benti asks when she runs immunisation sessions among the herding communities of Ethiopia’s arid Afar region.

Yet, as the Sister visits herders’ tents scattered across dusty plains dotted with foraging cattle, the answers rarely add up.

Semeli Basule thinks her eldest child Sami Hassan has had all his vaccinations. Six-month old Elema needs other vaccines, she believes. Unfortunately, both children’s vaccination cards have been lost.

“We have evidence that Elema has been vaccinated,” says Sister Benti, responsible for immunisation in Awash Fentale woreda*, “The problem of having no card is that we do not know how many vaccinations Sami has had.”

Daunting barrier

While living things count for Afar’s herding communities, their very value means people have a distinct aversion to revealing their existence. That includes not sharing the number of goats, cattle and camels in their herds, not making note of birth dates and having only an approximate idea of their own and their children’s ages.

For heath workers like Sister Benti committed to immunising Ethiopia’s children, this can be a daunting barrier.

Despite reticence on numbers, one statistic speaks very clearly. At the last recording, only 23% of Afar’s children had been vaccinated against diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis - a far cry from the 84% coverage rate in the nation’s capital, Addis Ababa.

Monthly two-day effort

Ethiopia’s government has recognised that the only way to improve immunisation rates among children in these pastoralist communities is through routine outreach programmes like the one taking place today.

Sister Sofia’s visit to Mirahot is part of a monthly two-day effort during which nurses and health extension workers will seek to immunise as many eligible children living in the seven rural kebeles in Awash Fentale as possible.

The programmes entail transporting vaccines by automobile and motorbike to and from far-flung clinics that have vaccine storage refrigerators.

To ensure the numbers do add up, the programmes also require keeping track of pastoralist families who can move as often as twice a year in search of water or pasture.

Awareness campaigns

Half a decade ago, it was not enough to find families. Sister Amelework Eshetu had to convince parents that immunisation was not a type of birth control – a dire threat for Afar’s people who hope to have as many children as possible as a safeguard against the difficult conditions under which they live.

Sister Eshetu remembers being driven away from a family at gunpoint. She successfully turned to the family’s neighbours, asking them to convince the father that allowing his pregnant wife to be vaccinated against tetanus could avert a fatal illness in the yet-to-be-born baby.

Thanks to awareness campaigns and the efforts of health extension workers recruited from their own communities, hostility towards vaccination has receded dramatically in Afar. Now, there are signs that access to accurate population and healthcare data is improving.

Unlike the population they serve, the immunisation outreach workers are not averse to counting. With their detailed knowledge of the community, they estimate that there are some 500 children below the age of 12 months in Awash Fentale. They expect to fully immunise 420 of them this year.

*A woreda is the third-level administrative division of Ethiopia. Woredas are composed of a number of wards (kebele), or neighbourhood associations, which are the smallest unit of local government in Ethiopia.

Sister Sofia visits Mirahot to immunise as many eligible children as possible in the seven rural kebeles

| NAME: | Sister Sofia Benti |

| PROFESSION: | nurse responsible for immunisation in Awash Fentale woreda* |

| EXPERIENCE: | monthly two-day campaign to immunise as many eligible children living in the seven rural kebeles in Awash Fentale as possible. Requires keeping track of pastoralist families who can move as often as twice a year in search of water or pasture. |

| BIGGEST CHALLENGE: | establishing immunisation schedules in Afar region’s herding communities, where parents have only an approximate idea of their own and their children’s ages. |

| LOCATION: | Awash Fentale woreda* |

| POPULATION: | 16,600 |

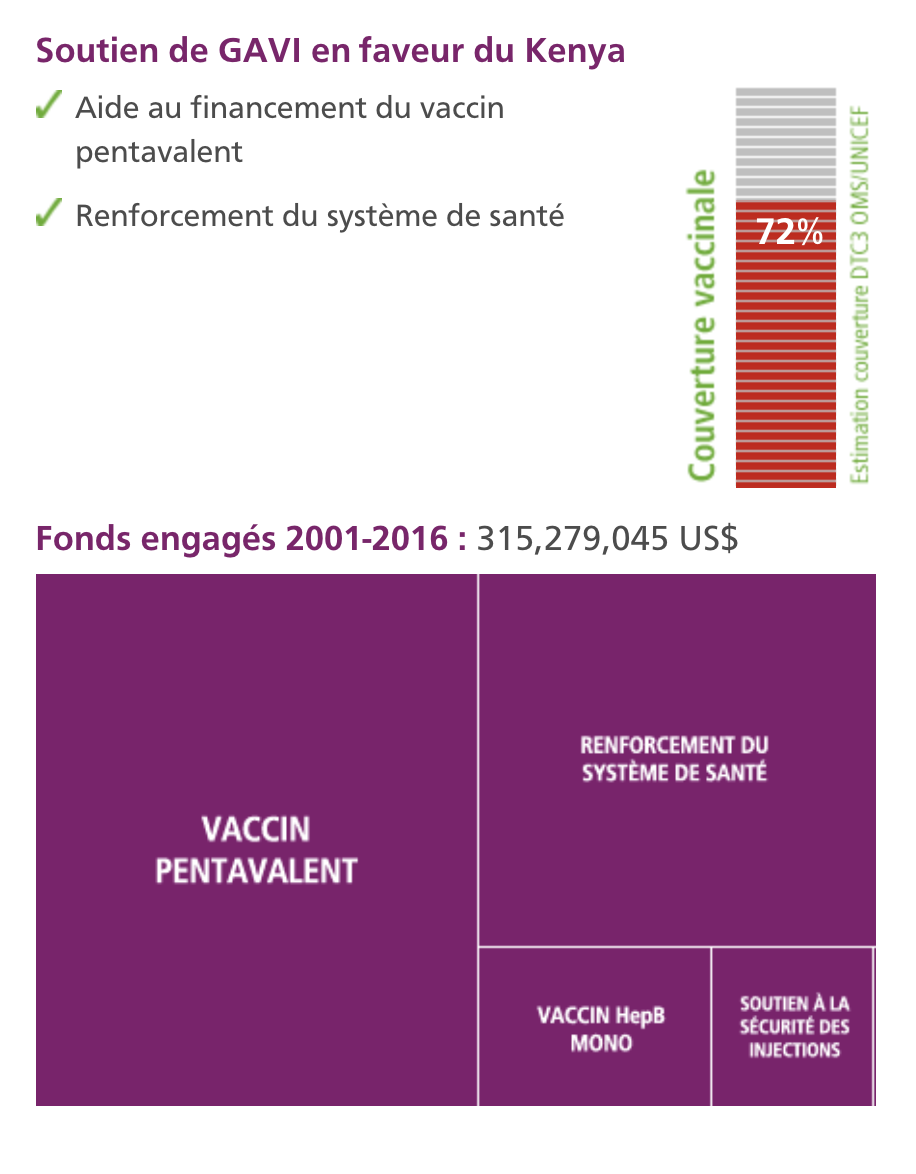

Kenya

Strengths

The Government has made a strong commitment to improving the immunisation coverage following a recent survey showing lower figures than prevously reported.

Challenges

Strong disparities between urban and rural areas with respect to overall access to health care; highly diverse population, with more than 80 languages spoken; low level of education.

Overview

In rural Ethiopia, counting lives means revealing their existence, so communities have only an approximate idea of their children’s age. For the people committed to immunising Ethiopia’s children, this can be a daunting barrier.

Outreach workers like Sister Sofia Benti in the State of Afar – who staffs a new Government initiative to increase immunisation in herding communities – are finding ways to shift this numbers culture as they seek to reach every child.

Strengths

The Government has made a strong commitment to improving the immunisation coverage following a recent survey showing lower figures than prevously reported.

Challenges

Strong disparities between urban and rural areas with respect to overall access to health care; highly diverse population, with more than 80 languages spoken; low level of education.

Overview

In rural Ethiopia, counting lives means revealing their existence, so communities have only an approximate idea of their children’s age. For the people committed to immunising Ethiopia’s children, this can be a daunting barrier.

Outreach workers like Sister Sofia Benti in the State of Afar – who staffs a new Government initiative to increase immunisation in herding communities – are finding ways to shift this numbers culture as they seek to reach every child.

Question&Answer

Dr Kurkie Abdissa, Director, Urban Health Promotion & Disease Prevention and National Coordinator for Maternal and Child Health and Immunisations Services, Ethiopia

Q The Ethiopian government and partners recently reviewed the drop in immunisation coverage figures from 80% to 65.7%. What was the impact of this change on the health system ?

Dr Abdissa: once we recognised that coverage was low – through the review you mentioned and because of the emergence of outbreaks, which provided further evidence - we revitalised our entire immunisation programme from the central to regional, woreda* and even to the kebele* level. We are also improving the cold chain system as we introduce new vaccines.

Ethiopia is a big country, with very diverse population and geography and equity issues. There were zones and even regions with low coverage; so the first thing to do was build more hospitals, more clinics, health centres, then fill those facilities with medical equipment and supplies and then train our staff.

We now have a very exemplary kind of structure, with two female health extension workers for each kebele – locally recruited women who are connected to their communities through common language and culture. This health development army is a very important tool for overcoming barriers related to culture, norms and values on the demand side.

Q Coverage is much lower in rural than in urban areas and is even lower in herders' areas. What is the Ministry of Health doing to narrow this gap?

Dr Abdissa: our policy is framed around commitment to reaching previously unreached communities in Ethiopia through a decentralised system. Ethiopia is divided into states and regions, which individually have capacity to address the issue of equity. We give special assistance to these regions to engage their own health extension workers, to build their own health systems and to improve their engagement in the national health system.

We have developed a special approach for pastoralist regions: we use not only fixed posts but also an outreach service. This is more fitting because some pastoralist communities move seasonally, so you have to follow them and make sure children get the antigens that they need.

We have also developed another procedure, woreda-based planning, to address equity. The woreda representatives sit down and discuss and agree on what measures to take next year. Consequently the cabinet of the kebele or ward has a chance to sit down with health bureaus and to discuss and agree on targets, ensuring sufficient budget allocation.

Q What is the GAVI Alliance’s contribution to immunisation in Ethiopia?

Dr Abdissa: GAVI is one of the most wonderful innovative examples of a public-private partnership, and its assistance to Ethiopia is huge, specifically in the assistance we have gotten in introducing new vaccines - life saving vaccines from diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis to pentavalent and pneumococcal vaccines.

Then you can consider the current new type of assistance that we got this year – Supplemental Immunisation Activities. When immunisation coverage is lower, we can now supplement it with a campaign. Overall the support that we get from GAVI is helping us in saving lives.

Q Which new vaccines is GAVI helping Ethiopia introduce?

Dr Abdissa: we are planning on introducing rotavirus vaccine and conducting a meningitis A campaign before the end of the year. Diarrhoea is potentially fatal in babies and very young children; 30% to 40% of diarrhoea is caused by the rotavirus.

*A woreda is the third-level administrative division of Ethiopia. Woredas are composed of a number of wards (kebele), or neighbourhood associations, which are the smallest unit of local government in Ethiopia.

Q Which new vaccines is GAVI helping Ethiopia introduce?

Dr Abdissa: we are planning on introducing rotavirus vaccine and conducting a meningitis A campaign before the end of the year. Diarrhoea is potentially fatal in babies and very young children; 30% to 40% of diarrhoea is caused by the rotavirus.

*A woreda is the third-level administrative division of Ethiopia. Woredas are composed of a number of wards (kebele), or neighbourhood associations, which are the smallest unit of local government in Ethiopia.