AS NIGERIA’S FEDERAL GOVERNMENT STRIVES TO OVERCOME REGIONAL INEQUITIES IN VACCINE ACCESS, INDIVIDUALS ARE CONTRIBUTING TO A STRONGER IMMUNISATION SYSTEM

Yusuf Ibrahim is a devout Muslim. He is also a convert: not in his religious faith, but in his beliefs about immunisation.

Firm-jawed, sitting with his broad shoulders back and his hands placed firmly on his legs, he speaks with passion, recalling a time when he drank in the words of people he considered more learned than himself, accepting them as gospel. “Elders told us vaccinations were there to control the population. Everyone believed them – they believed it themselves – so why would I think anything different?”

Western plot

Rumours that vaccinations are the product of a Western plot to ‘control the Muslim population’ abound in Nigeria, although no one is entirely sure of their origins. Growing up in a tiny farming village an hour away from Minna, Niger State’s capital city, Yusuf was told this as fact.

“At some point – I don’t recall when – I was told that vaccinations make men impotent. It made sense to us. The elders told us, ‘Why else would these people who don’t know you give you anything for free? They are doing it for family planning.' And at the time I believed it.“

Near tragedy

It took a near tragedy to change his heart and mind. Yusuf will never forget the vision of his first-born daughter Saratu, then two years old, when she became dangerously ill. She was coughing and she found it hard to breathe. Then she grew tired, and then limp.

His wife begged him for days to be allowed to take her to the doctor and then, with more desperation, to the hospital. As life seemed to drain from her body, her condition raised the spectre of the heart-breaking events that repeatedly befell the small rural community where Yusuf grew up, as young children were snatched from their families.

Pneumococcal pneumonia

His beloved daughter had pneumonia – an infectious disease that globally claimed the lives of 1.3 million children under the age of five in 2011, of which 129,000 were in Nigeria.

“I looked at my little girl and I knew what was going to happen,” says Yusuf. “When I was a young man I saw plenty of children die. I knew how they looked, and it was my little girl that looked that way now.”

Yusuf had been told by his village elders to stay away from hospitals and Western medicine altogether. Frantic at the thought of losing his first child, he agreed to allow her to enter a hospital.

“I don’t know what they did, but they gave my little girl life again,” says Yusuf.

Preserve life

He began to talk his beliefs through with the physicians, and gradually they convinced him that they were there simply to preserve life and that had his child been given the right vaccination, she might have been spared this ordeal.

A decade after his first born faced death and stared it down, Yusuf, now aged 32, is an advocate in his own community: Unguwar Daji, a shanty town without regular power or sanitation services straddling the northern edge of Minna. He makes his way through the maze of streets and orange-dusted back alleys, knocking on the doors of semi-permanent homes with corrugated iron roofs and explaining to families why immunisation is so important.

One of them

“If a man’s wife has just had a child, I go and speak to the man and tell him why they need to have a vaccine. And they believe me because I am one of them. We work the same jobs, we are from the same villages, and they see that all of my children have been vaccinated,” he says.

Unguwar Daji is populated entirely with families like the Ibrahims, poor folk who moved to the city from small villages in search of jobs, desperate to make their lives – and those of their children - easier. Many of them still cling to the old ideas about vaccination.

Strategic campaign

It will take time, and a strategic campaign to educate them – everything from talking to elders to asking pop stars to write songs about the benefits of vaccinations.

For the most diehard believers, however, Yusuf’s arguments seem to be the most effective weapon. He cannot read, but he is an eloquent spokesperson.

It is time to walk alongside his neighbours to the mosque for Friday prayers, and Yusuf has donned a pristine cream-coloured shalwar kameez. He is surrounded by his four, perfectly groomed children – among them 13-year-old Saratu.

“This is my family,” Yusuf says with a broad smile. “God is great.”

“This is my family,” Yusuf says with a broad smile. “God is great.”

| NAME: | Yusuf Ibrahim |

| PROFESSION: | community immunisation advocate |

| EXPERIENCE: | changing his anti-vaccine beliefs after doctors explained that pneumococcal vaccine could have spared his daughter from a near fatal case of pneumonia. |

| BIGGEST CHALLENGE: | convincing local community that vaccinations are not a Western plot to control Nigeria’s population. |

| LOCATION: | Unguwar Daji, a shanty town on the northern edge of Minna, Niger’s State capital |

Nigeria

Strengths

Recognition by federal government of the need to increase coverage plus commitment by some state governors to have a strong immunisation programme.

Challenges

Variable immunisation coverage by state and within states with a range of 10% to 80%, uneven infrastructure, large country with multiple geographical barriers, anti-vaccine movement.

Overview

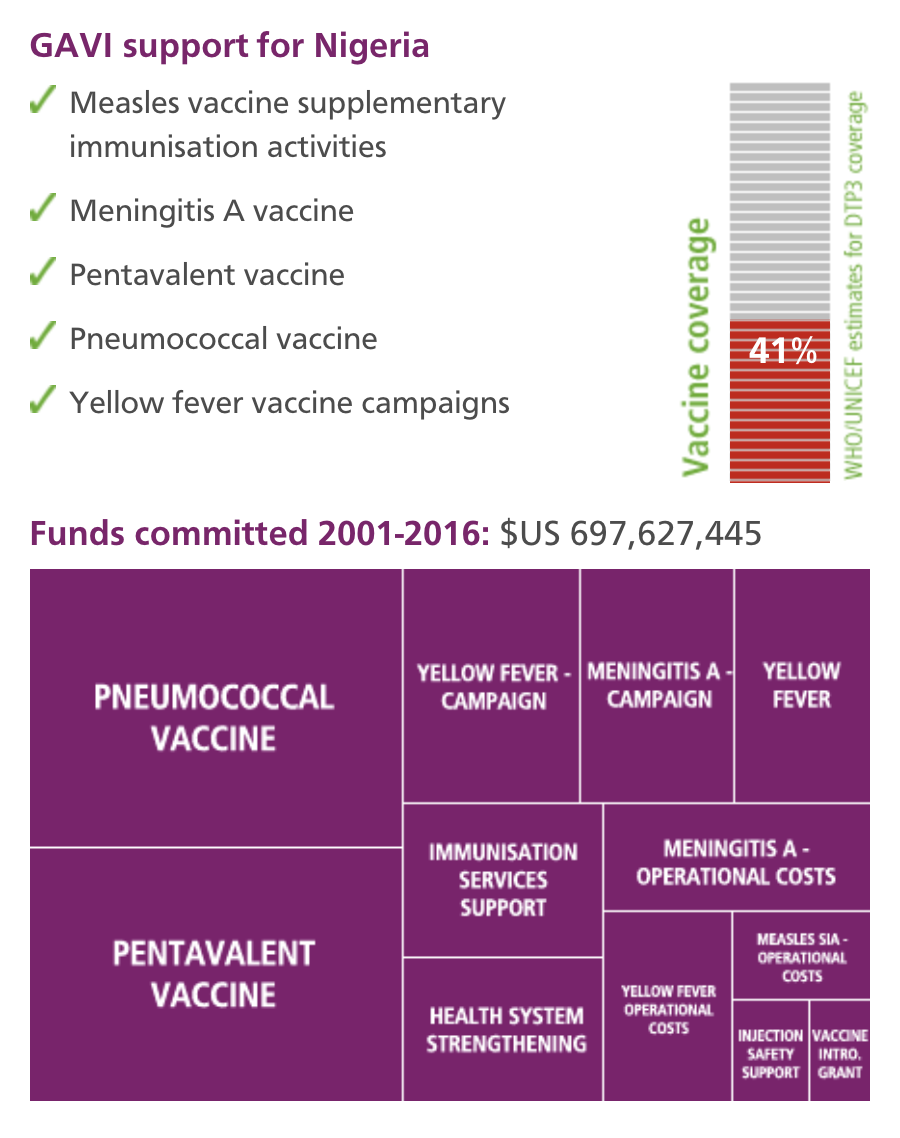

Nigeria is a large country with a federal system of government in which each state organises and delivers health care autonomously. This system translates into marked differences in immunisation coverage between states. As Nigeria strives to address these inequities with support from GAVI, individuals ranging from Yusuf Ibrahim, a devout Muslim and community immunisation advocate in Niger State to Dr Dayo Adeyanju, Ondo State Commissioner for Health, are building a stronger immunisation system one community at a time.

Strengths

Recognition by federal government of the need to increase coverage plus commitment by some state governors to have a strong immunisation programme.

Challenges

Variable immunisation coverage by state and within states with a range of 10% to 80%, uneven infrastructure, large country with multiple geographical barriers, anti-vaccine movement.

Overview

Nigeria is a large country with a federal system of government in which each state organises and delivers health care autonomously. This system translates into marked differences in immunisation coverage between states. As Nigeria strives to address these inequities with support from GAVI, individuals ranging from Yusuf Ibrahim, a devout Muslim and community immunisation advocate in Niger State to Dr Dayo Adeyanju, Ondo State Commissioner for Health, are building a stronger immunisation system one community at a time.

Question&Answer

Dr Olusegun Mimiko, Ondo State Governor, and

Dr Dayo Adeyanju, Ondo State commissioner for health

They have yet to be the subject of an animated series or a blockbuster movie but in Nigeria’s public health landscape, Dr Olusegun Mimiko, Ondo State Governor, and Dr Dayo Adeyanju, Ondo State commissioner for health, are the ultimate dynamic duo.

Dr Adeyanju’ s super powers are in evidence today as he shows off the Ondo State Cold Storage Facility, a brand new building that sits alongside a construction site where a health centre is taking shape - and barely 20 feet from the crumbling stone barn that formerly served as the vaccination store.

For Adeyanju, the site represents a good metaphor for health care in his state. “Our people are enjoying the best health care in the country,” he says. “But we are working on projects to make it even better.”

Raising the level

Nigeria’s system of government is federal, and each state has considerable autonomy, including in how it organises and delivers health care. This system translates into marked differences in the quality of health care and health between states. Nigeria’s other states have now started to judge Ondo as the bar against which to measure their own health care services, and Dr Adeyanju wants to keep raising the level.

“We have a very supportive governor, Dr Mimiko, and the entire state government is very committed to health services,” he says.

Good guy doing a good job

Governor Mimiko and Dr Adeyanju first met more than three decades ago when Adeyanju was an impressionable 12-year-old. Dr Mimiko had come to his school to give a talk about the health profession. “We spoke for a while and I said to myself afterwards, ‘He seems like a good guy doing a good job at a young age…maybe I’d like to be like him.’”

As Dr Mimiko moved up the public service ladder to become Ondo State commissioner for health, Dr Adeyanju graduated medical school and began working at the state hospital. This first job left him feeling discouraged. “I saw that I couldn’t help most people,” he says. “I thought it would be better for me to be in an area where I can prevent all these things in the first place.”

Grass-roots programmes

Dr Mimiko saw that the young doctor was frustrated and could better fulfil his ambitions in public health, so he invited Adeyanju to come and work for him at the ministry. Together they embarked on a grass roots programme that succeeded in dramatically reducing HIV and malaria prevalence in Ondo State. Then, in 2009, Mimiko was elected to the governor’s seat. With his new position came great opportunity.

“When we came on board, we had a grossly underfunded health sector with poor infrastructure, poor leadership and ill-motivated workers,” Dr Adeyanju says. “We had a state that still had polio in one of the local government areas and where infant mortality was pretty high and under-five mortality was also too high.”

Revolutionising the system

The new governor made health a priority for his administration and embarked on revolutionising the system through the Abiye project -- the Yoruba word for motherhood.

Pregnant women are the major target of the Abiye programme. Each woman gets a smart card containing biographical data, which allows health workers to track the medical history of her family. The card makes it easier to schedule postnatal care, including vaccinations for babies.

Increasing access to vaccination was the first step. But then there was the question of how to store and transport vaccines.

“The old state cold store had not been used for two months when we saw it,” Adeyanju recalls. “The ramshackle building appeared to have sat derelict for decades, with crumbling walls, a dank odour and an electrical fuse box that looked like a 10-year-old’s science project.” The generator supplying power to the all-important fridges had been bought in 1978.

Cornerstone

“I told the Governor this was not good enough, and within weeks he had set aside funds for a new store and construction was underway,” he says.

Vaccination coverage in the state is now among the highest in the country, and within the next few months Ondo will begin the roll out of pentavalent vaccine - a single vaccine that protects children against five potentially lethal diseases: tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis (whooping cough), hepatitis B and Haemophilus influenzae type b (which causes meningitis and pneumonia). Pentavalent is currently used in some 170 countries, and is increasingly being given to children in developing countries with support from the GAVI Alliance.

“The cornerstone of our health programme is the Routine Immunisation Programme, which is boosted by national immunisation days – none of which would be possible without GAVI’s support,” Dr Adeyanju says.

As Nigeria seeks to address fragmentation in its health care the GAVI Alliance, in parallel, is working on tailored approaches to supporting the country’s immunisation systems, which need to be tackled state by state. “With these generous donations we can provide a model that could transform the whole country,” Dr Adeyanju says.

And perhaps recruit a few additional super heroes along the way.