A TEAM OF OVER 100,000 TRAINED FEMALE COMMUNITY WORKERS DELIVERING BASIC HEALTH SERVICES DOOR-TO-DOOR HOLD THE KEY TO REVIVING PAKISTAN’S IMMUNISATION PROGRAMME

Draped in a traditional bright sari but bearing the modern tools of a vaccinator, 30-year-old Shankotila Bai has the past and present weighing heavily on her shoulders.

For a country where vaccines are widely available, Pakistan’s recent record on immunisation is poor with only half of its children fully immunised. Now, Bai and the other 100,000 trained Lady Health Workers in Pakistan are expected to increase immunisation coverage rates the hard way – by walking door to door.

Bai’s daily objective is to visit 8 to 10 families in her home village of Mithrio Bhatti, located in the Thararkar district of Sindh Province. Priority is given to vaccinating all children and mothers who have not been to the nearest health clinic in Mithrio for their immunisations.

Mithrio Bhatti is a poor village, but a calm one, where Hindus and Muslims live peacefully side-by-side. Equipped with a cold box and a medical bag, Bai will make three stops before lunch time.

Get up to speed

One of her visits is to Seeta Bai, 27, whose infant son Jetesh was born with the help of a local dai (traditional birth attendant). Wearing a black taweez to ward off evil spirits, the mother appears tired and weak. She had not brought her child to the health clinic for vaccination.

Now Jetesh will need to get up to speed, starting with oral polio vaccine and followed by injectable pentavalent vaccine in the right thigh and pneumococcal vaccine in the left. Cuddling the baby to her breast, Seeta looks askance as each jab is administered.

At stake

Now poised to enter its third decade and a model for developing countries worldwide, the Lady Health Worker programme is seen by Pakistan’s government as critical to reaching more children with immunisation.

Much is at stake. With some five million babies born every year and unrelenting challenges like flash floods and the presence of one million internally displaced persons, Pakistan is also confronting the spread of preventable communicable diseases.

For example, since October 2012, the country has seen over 20,000 suspected measles cases and some 500 measles deaths. A nationwide review showed the measles vaccine was available – but children simply were not getting it.

Lady Health Workers have been salaried government employees since January 2013, but the path to attaining this status was not without obstacles.

In its early days, the programme had only quasi-official rank. Later it was devolved from the central government to the country’s provincial authorities, after which it was suspended for two years.

Training

Like other Lady Health Workers across Pakistan, Bai attended a six/month course preparing her to attend to the basic health needs of the women and children among the 2,000 people living in her village.

Some particularly well-educated workers, like Bai – who completed grade 12 - have received training that qualifies them to give vaccines.

The real strength of the Lady Health Workers lies not just in their training but also their role as trusted members of the community they serve.

Health house

When she is not making door-to-door visits, Bai operates out of a clinic she calls the Health House – in reality, a spare room in the house she has called home since marrying local tailor Halo Mai and where she brings-up her own three children.

Before she starts work as a health worker at 8am each day, Bai has already milked the goat, prepared and served her family’s breakfast of chapatti, chutney and yoghurt drink; fed the cattle; and done her housework.

It is a daily routine she shares with many other women in her village and brings the trust and respect essential for the success of her main role: health education.

Spread awareness

As a Lady Health Worker, Bai must spread awareness among women of child-bearing age about hygiene, immunisation, pre- and post-natal care, nutrition, family planning and the services available to them at nearby health centres.

Against the pale desert background, women dressed in vibrant colours arrive, greet Bai and then sit in a semicircle in her Health House.

As she shows them a book of illustrations, she exhorts mothers to take their babies to the health centre six times within the first 15 months of birth. These six visits, she says, will protect every child from nine illnesses including pneumonia – which all of the mothers know and fear.

Pneumonia remains the number one cause of death among young children in Pakistan, but in 2012, with support from GAVI, Pakistan became the first South Asian country to introduce the pneumococcal vaccine. By training Bai and 100,000 Lady Health Workers, the foundations are now in place to ensure this life-saving vaccine can reach every Pakistani child.

Shankotila Bai, Lady Health Worke

Shankotila Bai, Lady Health Worker

| NAME: | Shankotila Bai |

| PROFESSION: | Lady Health Worker |

| EXPERIENCE: | six months training to provide for basic health needs of women and children living in her village; raising awareness among mothers of child-bearing age about the importance of health care. |

| BIGGEST CHALLENGE: | convincing mothers to immunise their children in a country where preventable communicable diseases are on the rise but only half of children are fully immunised. |

| LOCATION: | Mithrio Bhatti, located in the Thararkar district of Sindh Province |

| POPULATION: | 2,000 |

Pakistan

Pakistan

Strengths

Commitment to improving immunisation system by training outreach workers based in small hard-to-reach communities as vaccinators.

Challenges

Decentralised, fragmented immunisation system and uneven coverage, as evidenced by on-going polio transmission and measles outbreaks; widespread displacement of children following floods and other disasters; security threats.

Overview

For a country where vaccines are widely available, Pakistan has a poor recent record on immunisation, with only half of its children receiving all needed vaccines. Trained Lady Health Workers like Shankotila Bai, who lives and cares for people in the village of Mithrio Bhatti in Sindh Province, are the country’s next best hope. Draped in traditional saris but bearing the modern tools of vaccinators, these trusted village health advisers could hold the key to bringing full immunisation to Pakistan’s children.

Question&Answer

What next for immunisation in Pakistan: the government and two key partner organisations offer their views

Dr Jehanzeb Khan Aurakzai, Director General, Ministry of National Health Services Regulations & Coordination

Q What do you believe are the main challenges to increasing immunisation coverage in Pakistan? What on-going activities offer the best opportunities?

Dr Jehanzeb Khan Aurakzai: until recently, the routine immunisation programme and Polio Eradication Initiative were running in parallel rather than complementing each other. Performance of districts has been gauged based on their performance in polio-specific activities and, consequently, routine immunisation has been badly neglected. The lack of clarity on exact roles and responsibilities is yet another obstacle in effective performance of the national immunisation system.

Q What kind of solutions to this problem are you looking at?

Dr Jehanzeb Khan Aurakzai: the newly formed Ministry of National Health Services, Regulations and Coordination will play an important role in overall coordination of immunisation services throughout the country.

Measures to streamline mechanisms for coordination with provinces, line ministries, donors, and partner organisations are being developed and put in place. An expanded programme on immunisation office, now placed within this ministry, will be the hub of this activity and take a lead role.

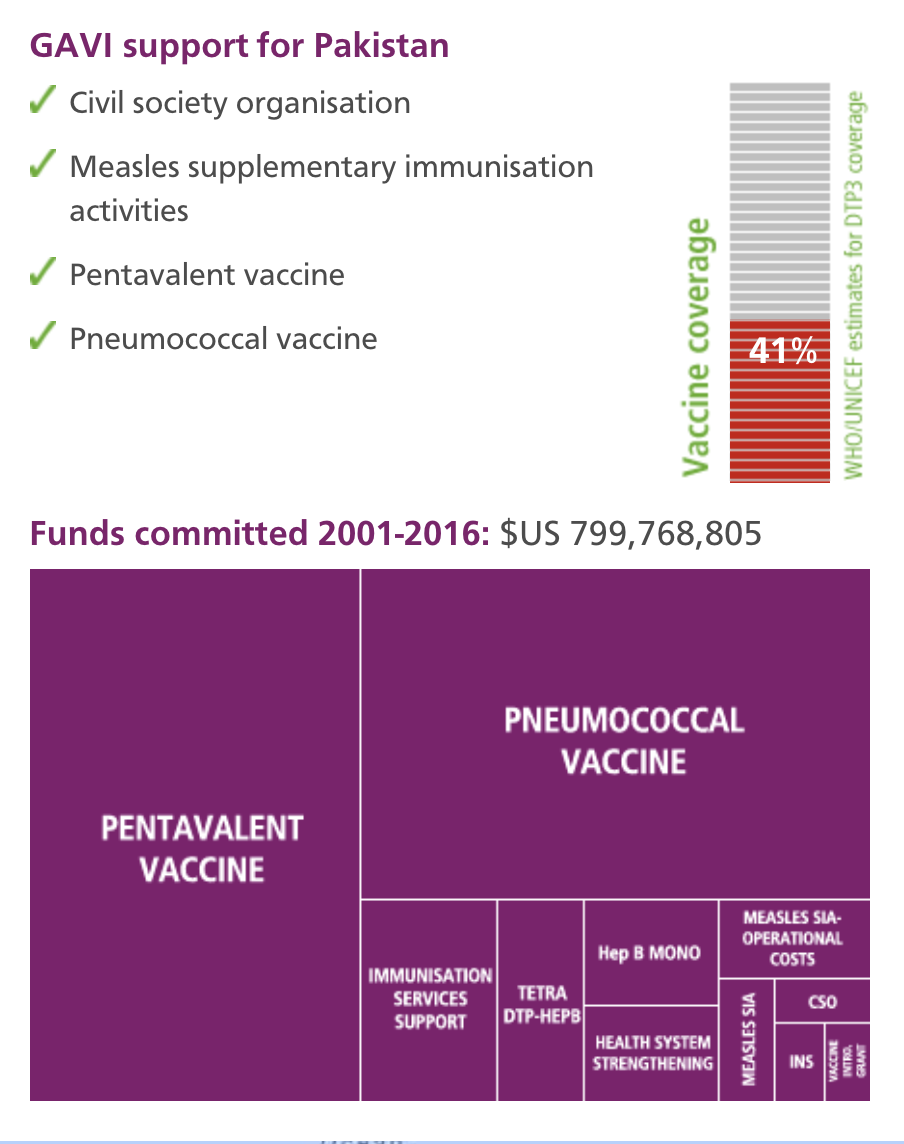

Q From your viewpoint, what has been the most important benefit of GAVI support?

Dr Jehanzeb Khan Aurakzai: the process of co-operation and partnership with civil society initiated by GAVI has resulted in enthusiastic and unprecedented activity of civil society actors. They have engaged proactively with the government at all levels and helped in advocating the government-led initiatives.

GAVI’s assistance has also provided an opportunity to bridge district-level financial and operational gaps. However, there have been issues with efficient utilisation of these resources to bring about the intended improvements in district programmes. Enhanced capacity of the federal government for supervision is the only solution to ensuring the rational use of resources by the provinces.

Dr Quamrul Hasan, Medical Officer, World Health Organization, Pakistan

Q What do you see as the greatest challenge to getting all Pakistani children immunised?

Dr Quamrul Hasan: the key challenge is that public health has not been a national priority. Lack of accountability of service providers and their supervisors, an inadequate and inefficient healthcare delivery infrastructure and low pro-active public demand for immunisation are other major contributing factors.

Q What opportunities are there to turn the situation around?

Dr Quamrul Hasan: the greatest opportunity in immunisation service delivery in Pakistan is the 100,000-strong cadre of Lady Health Workers. In Pakistan’s cultural context, this group is the perfect match to deliver primary health care - including immunisation services - to the community in the most efficient way.

The other positive going for Pakistan is general acceptance of immunisation among communities, which could easily be transformed into a pro-active community demand for immunisation.

Resistance to immunisation is actually not as high as is often portrayed.

Q Have there been recent improvements in immunisation?

Dr Quamrul Hasan: in the past decade, three new and under-used vaccines – hepatitis B, Haemophilus influenzae type b and pneumococcal vaccines - were added to the national childhood immunisation schedule. These vaccines have prevented hundreds of thousands of illnesses and deaths among young children. Introduction of auto disable syringes into the national immunisation system also has made a significant contribution by averting unsafe use of injections.

Q How has GAVI contributed to helping reach this country’s goal for immunisation of its children?

Dr Quamrul Hasan: without support from GAVI, Pakistani children would not have access to new, life-saving vaccines like Haemophilus influenzae type b and pneumococcal vaccines.

Dr Saadia Farrukh, Health Specialist, UNICEF Pakistan

Q In 2001, Pakistan’s health care began a process of devolution – where authority was moved from the central government to provincial authorities. What has been the impact of this change on immunisation?

Dr Saadia Farrukh: before devolution, the federal government was responsible for the procurement and supply of vaccines, injection equipment, cold chain and logistics, training, monitoring and evaluation and technical guidance.

After devolution, when district-level preventive programmes took over, there was no longer clear allocation of funds for immunisation. Logistical responsibilities also were handed over to the provinces. There has been a clear negative impact on performance.

Q Pakistan has had many immunisation campaigns. Have they helped matters?

Dr Saadia Farrukh a lot of effort has been put into immunisation campaigns against polio, measles, and neonatal tetanus. These campaigns have actually negatively affected the ability of staff to deliver routine immunisation services.

The danger in relying on campaigns to maintain high coverage in the absence of a good routine immunisation system cannot be overemphasised. When intermittent campaigns are used to boost poor routine coverage levels, the number of infants susceptible to diseases inevitably rises between campaigns.

Q What are the most important next steps for Pakistan?

Dr Saadia Farrukh: while Pakistan has been able to avert an estimated two to three million infant and child deaths from life-threatening diseases like diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough and measles, the sad truth is that immunisation coverage has stagnated over the past decade.

Given that we have so much catching up to do, the foremost challenge for Pakistan is to strengthen its health system so as to improve routine immunisation.