Introduction

Almost a decade ago, Kofi Annan, former Secretary-General of the United Nations, remarked that The Paris Agreement, which aims to prevent global temperatures rising by more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, “marks the beginning, not the end, of the road. It is now our collective duty to hold our leaders to account and ensure that they turn promises into action – especially in the world’s most vulnerable regions”.

Nine years have since passed, and the world marked 2024 as the first time global average temperature exceeded the 1.5°C target for 12 months in a row. The latest UNEP Emissions Gap Report projected that current global mitigation policies would put the world on a path for a temperature increase of 2.6–3.1°C over the course of the 21st century.

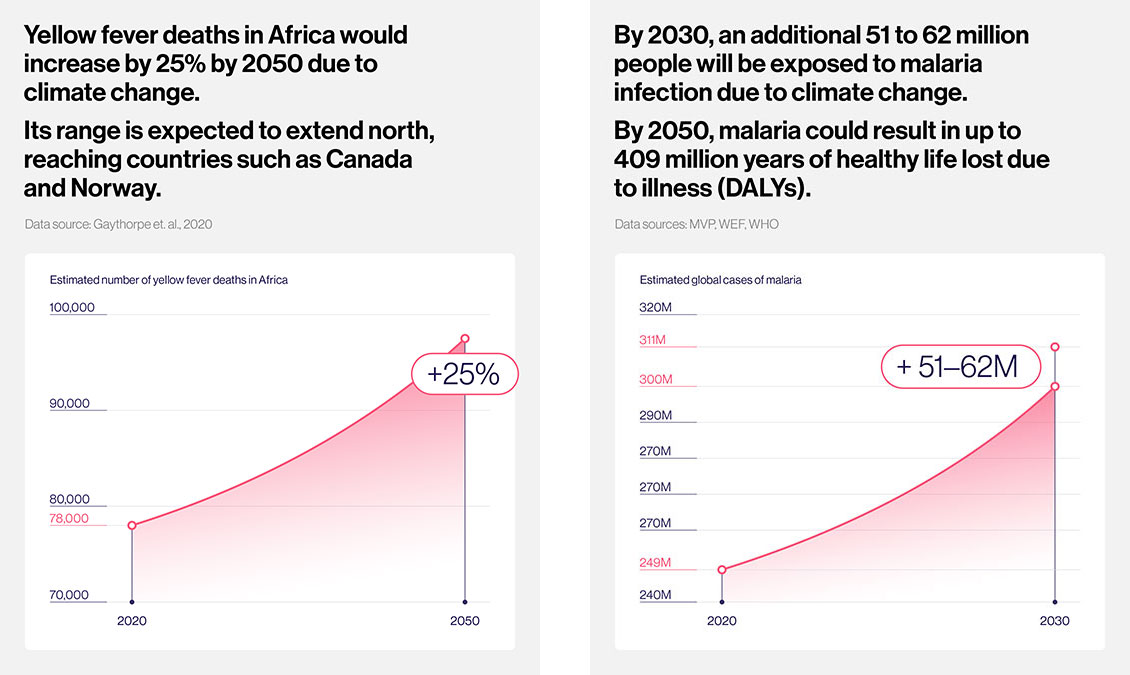

The climate crisis is the greatest health threat to the world and arguably the existential threat to humanity. Changing climatic conditions are already putting more people at risk of life-threatening infectious diseases such as malaria, dengue and cholera. And the risks are increasing: slow-onset climate events are changing the social, economic and natural systems that underpin the geographical distribution and incidences of infectious diseases. A study of 375 known infectious diseases found that 218 of them can be aggravated by climate change. By 2050, an additional 500 million people may be at risk of exposure to vector-borne diseases.

Meanwhile, more frequent and intense extreme weather events would directly damage essential health infrastructures that could cost health systems US$ 2–4 billion a year by 2030. The associated disruption to access and delivery of health services further increases the risks of cascading health emergencies and disease outbreaks, with vulnerable groups such as children and hard-to-reach communities particularly susceptible to the escalating risks.

At the same time, Universal Health Coverage remains a distant goal for many countries; and half of the world’s population is yet to be fully covered by essential health services. Two billion people are facing financial hardship due to out-of-pocket health spending, which is further increasing their vulnerability to the cascading health impacts of climate change.

Health systems under strain

As risks and exposures to climate-sensitive infectious diseases continue to rise, so too will the strain on health systems. Experience from the COVID-19 pandemic and other major outbreaks has shown how health systems across the world can be stretched thin during a public health emergency, leaving millions without vital care when these services were needed the most.

During the pandemic, essential immunisation levels declined in over 100 countries, and there was widespread disruption to essential health services, leading to a resurgence of vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks such as measles, polio and yellow fever.

As of 2023, the number of ‘zero-dose’ children – those who have not received even a single basic vaccine – stands at 14.5 million globally: substantially higher than the pre-pandemic level of 12.8 million.

Analysts estimate a 47–57% probability of a similar global pandemic of the scale of COVID-19 in the next 25 years, even without taking into account the effects of climate change. The Global Health Security Index has shown that all countries remain dangerously unprepared to meet future epidemic events.

Low- and middle-income economies, especially those experiencing fragility and humanitarian crises, are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. These countries often have fewer resources and capacity to respond to health emergencies, and as such are at greater risk of infectious disease spillover and outbreaks. According to the International Committee of the Red Cross, 14 of the 25 countries most vulnerable to climate change are also experiencing violent conflict.

And the cost is mounting: by 2050, the cumulative cost for health systems globally to treat diseases caused by climate change could rise to over US$ 1.1 trillion.

At the same time, the number of climate-, weather- and water-related disasters have already increased five-fold since 1970. The climate crisis’s extensive damage to health systems, increased disruption of essential services and worsening of socioeconomic conditions are exacerbating the impact on people’s health and well-being, especially those living in low-income and vulnerable countries and communities.

Vaccines: a critical tool for climate change adaptation strategies

The impacts of climate change are expected to worsen, and this warrants a global response. The future burden of climate-sensitive diseases will depend on what interventions countries adopt in their adaptation strategies, and on the efficacy and resilience of their health systems.

Of the 64 countries that committed to building climate-resilient health systems under the Health Programme at the 26th Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP26 UK), only four countries developed or updated Health National Adaptation Plans between 2020 and 2022.

The key to success lies in being more intentional and proactive about building health system resilience and preparedness, notably through climate adaptation planning and health emergency preparedness systems. Targeted investments in integrated, preventive health measures to protect against key health risks and vulnerabilities, especially for vulnerable and hard-to-reach populations, can effectively increase resilience and minimise the chances for emergencies to escalate into further health hazards.

Vaccines have important co-benefits: lowering the risks of individuals contracting climate-sensitive infectious diseases. This helps reduce people’s vulnerabilities to the hazards of disease outbreaks, and in turn reduces the strain on health systems during emergencies when they are needed the most.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has consistently identified vaccines as a critical tool for climate adaptation strategies. By preventing death and disease and enabling people to live longer, healthier lives, immunisation brings economic benefits for individuals and societies, such as increased productivity and wages and reduced health care costs.

Universality and equity must be at the heart of climate adaptation strategies if they are to be successful. As routine immunisation is often delivered at the doorstep of communities, it has the potential to reduce the barriers to access for health services and serve as an effective platform to co-deliver other much-needed primary health services.

Vaccines: strengths and achievements

- Immunisation is the only intervention that brings the majority of households into contact with the health system five or more times during the first year of a child’s life – more than any other health intervention.

- A study covering 73 Gavi-supported countries shows that, for every US$ 1 spent on immunisation in the 2021–2030 period, US$ 21 are saved in health care costs, lost wages and lost productivity due to illness and death.

- Overall, an estimated 51.5 million deaths are expected to be averted due to vaccinations administered between the years 2021 and 2030, inclusive.

Call to action

The imperative to enhance the resilience of national health systems and sustain immunisation efforts as part of climate adaptation measures has never been more pressing.

This is why Gavi is calling for countries to explicitly include immunisation programmes in their National Adaptation Plans and Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessments; and align them with national immunisation strategies and primary health care plans to maximise potential climate and health co-benefits.

Gavi’s commitment

Gavi is already supporting countries to build resilience and mitigate the health risks and vulnerability related to climate change by rolling out vaccines that protect against seven diseases that are spreading rapidly as a result of climate change: dengue, meningitis A, Japanese encephalitis, yellow fever, cholera, malaria and typhoid.

For outbreak diseases such as yellow fever and cholera, Gavi is increasingly shifting towards preventive vaccination to avoid the disruption to health systems caused by outbreak response. Gavi’s Policy on Fragility, Emergencies and Refugees can be used for recovering and rebuilding health systems, protecting the most vulnerable after disasters or emergencies.

Gavi’s ask

In Gavi’s 2026–2030 strategic period, countries will continue to receive support to adapt to, and prepare for, climate impacts by expanding vaccine programmes to prevent outbreak-prone diseases at source. Gavi will make its largest investments in emergency stockpiles that can help respond to over 150 outbreaks. Gavi is also investing in better data on epidemiology, surveillance, modelling of vaccine use, and impact to improve our preparedness efforts and inform future responses.

This comprehensive package of support will deliver an unprecedented US$ 100 billion in wider economic benefits for countries and offer a proven return on investment for donors. To deliver on this ambitious plan, Gavi calls on countries to support Gavi’s replenishment to meet its target of US$ 9 billion for 2026–2030 and achieve the goal of immunising at least 500 million more children, saving a further 8‑9 million lives.

The human cost of climate-related disasters

- Extreme weather events affect about 189 million people in developing countries every year since 1991, of which 79% of recorded deaths in this period were in developing countries.

- The climate crisis impacts women and children differently and amplifies their risks and vulnerability across other dimensions of inequity. For example as many as 80% of people displaced by climate change are women.

- Climate-related disasters have claimed the lives of 510,837 people and affected another 3.9 billion between 2000 and 2019.

- In 2023 alone, climate disasters such as floods, wildfires, cyclones, storms and landslides claimed the lives of 12,000 people globally – 30% more than in 2022.

- Between 1970 and 2019, around 70% of global deaths associated with weather-, climate- and water-related hazards occurred in Least Developed Countries.

Immunisation: a critical pillar of climate adaptation

Immunisation prevents several climate-sensitive infectious diseases, promotes health system resilience and is an enabler of climate adaptation, particularly for vulnerable communities. This Gavi technical paper takes a deeper look at the critical role of vaccines on climate adaptation, and demonstrates how they can be integrated into national climate policies and strategies.

- Download: English | French | Spanish | Portuguese