SUCCESS WITH DUAL VACCINE INTRODUCTIONS AND OVERALL HIGH IMMUNISATION RATES MAKES GHANA A MODEL FOR OTHERS IN AFRICA

At a makeshift clinic set up on an empty stall at a market in rural Ghana, Felicia Kovie waits for her three-month-old son Godwin to be given injections that will protect him against six life-threatening childhood illnesses.

After Godwin nearly died just weeks earlier from a bout of pneumonia, Felicia Kovie, 38, is very aware of the importance of vaccinations for her four children.

“His sickness was severe and he was in hospital for three days,” she says, as traders around her noisily hawk their wares from vegetables and eggs to Tupperware containers and brightly-printed cloth. “I was worried he would die. That’s why I brought him here today because I don’t want my child to become sick again. I know these vaccines are to prevent disease.”

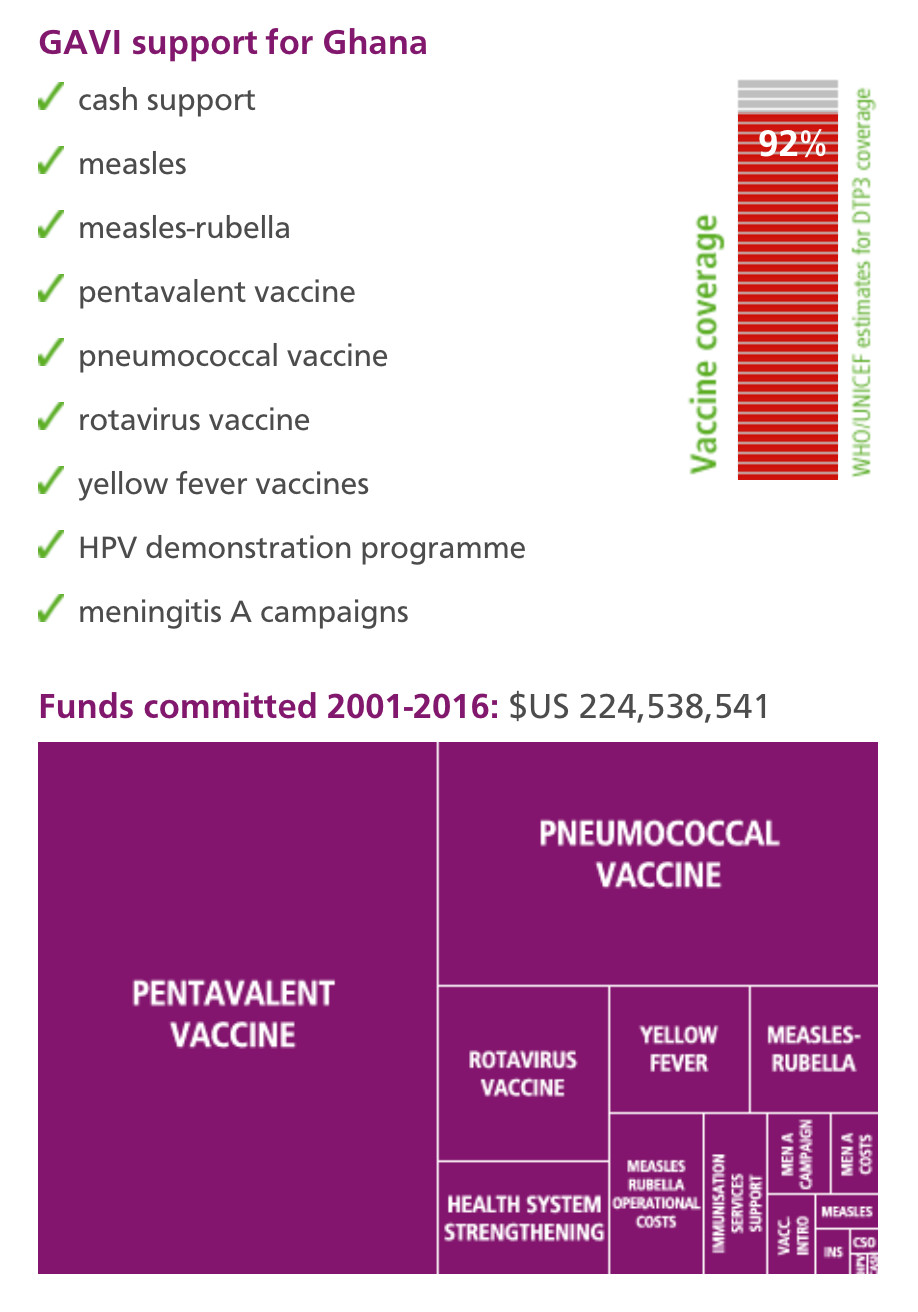

Godwin, like almost all children born in Ghana today, will be vaccinated against a swarm of diseases, including whooping cough, influenza, measles, yellow fever – and, since 2012, pneumococcal disease and rotavirus, respectively, the main causes of two of the world’s leading child killers, pneumonia and diarrhoea. GAVI helps fund the introduction of some of these vaccines, and supports Ghana’s state health service and local partners with training and improvement of refrigerated vaccine storage.

Double roll-out

The double roll-out of the pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines in 2012 was seen as a test for the West African country. It was the first-time any African country introduced two vaccines simultaneously, but the introductions passed off with very few hitches.

“It was important to continue to educate mothers and the public that there’s these new vaccines, and what they prevent,” says Cynthia Charpo, 30, a community health worker in Dodowa, a town north of Ghana’s capital, Accra. “Because it was a new thing, people wanted to know what reactions there might be. But most people just accepted it, and we are immunising even up to today, and nobody is complaining.”

Model

The success with the pneumococcal and rotavirus campaigns means that Ghana is increasingly a model for its neighbours.

Ghana’s ability to introduce two vaccines at the same time, and its general success with immunisations, is down to targeted training, national and local government support, good communication, and databases for vaccine coverage, says K.O. Antwi-Agyei, who heads the country’s national disease control unit.

“We put a lot into education and training,” he says. “We build a culture of data management and using data for decision making, and we have a decentralised system of government. In addition, we work closely with our civil society groups so that for us when we talk about a health system, it’s not the government structures alone. We use all available opportunities.”

Working

It is working: coverage of vaccines against meningitis, polio and diphtheria, tetanus and whooping cough are all above 90%, according to World Health Organization figures for 2012.

Measles, which used to kill more Ghanaian children than any illness apart from malaria, has been all but eradicated.

Loud-hailer

A short drive north of Dodowa, Esther Oku-Afari, a 49-year-old nurse, is setting up another outreach clinic in a bus station, calling mothers to the front with a loud-hailer.

In the 25 years that she has worked in this district, around the town of Larteh in the hills north of Ghana’s capital, Mrs Oku-Afari has seen the impact of vaccines on countless children.

“It’s been very good because hitherto, measles was common, whooping cough was common, but since vaccination has been going on, you can hardly now find somebody with these conditions,” she says. “I don’t remember the last time we had measles.”

Free for all children

GAVI’s funding of vaccines means that they are given for free to all children who need them – which is critically important, she adds.

“It’s a very big incentive because if they were supposed to pay, I doubt that there would be many people who could afford it,” Esther Oku-Afari says. Women visiting the clinic with their children gathered to listen behind her and nodded their agreement.

Challenges

There are still challenges, however. The area where these makeshift clinics were held is prone to heavy rains, and roads beyond the main towns are in poor condition here and in many places across the country.

Electricity for refrigeration of vaccines beyond the larger clinics can be scarce. And there are still small pockets of resistance, where families refuse to have their children immunised because of religious teachings or because of international anti-vaccination campaigners, whose propaganda people read on the Internet.

Success stories

But these are difficulties that Ghana is best placed to overcome, says Ebenezer Appiah-Denkyire, Director-General of the Ghana Health Service.

“We’re proud to say that because of our success stories, we are now able to introduce new vaccines that run without difficulty, and that’s a lot to do with the support we’ve received, including the role GAVI has played,” he says.