SUCCESS WITH DUAL VACCINE INTRODUCTIONS AND OVERALL HIGH IMMUNISATION RATES MAKES GHANA A MODEL FOR OTHERS IN AFRICA

At a makeshift clinic set up on an empty stall at a market in rural Ghana, Felicia Kovie waits for her three-month-old son Godwin to be given injections that will protect him against six life-threatening childhood illnesses.

After Godwin nearly died just weeks earlier from a bout of pneumonia, Felicia Kovie, 38, is very aware of the importance of vaccinations for her four children.

“His sickness was severe and he was in hospital for three days,” she says, as traders around her noisily hawk their wares from vegetables and eggs to Tupperware containers and brightly-printed cloth. “I was worried he would die. That’s why I brought him here today because I don’t want my child to become sick again. I know these vaccines are to prevent disease.”

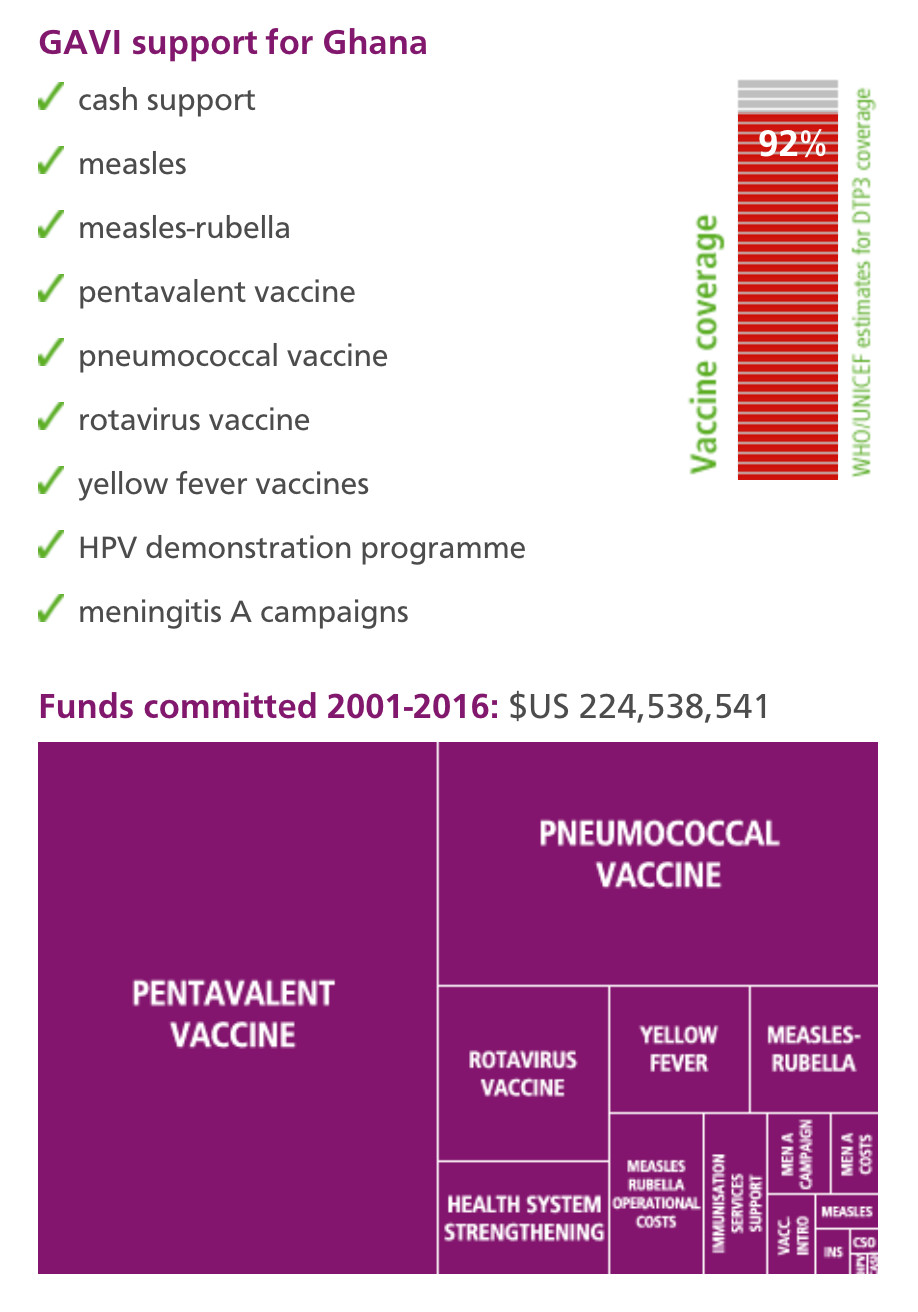

Godwin, like almost all children born in Ghana today, will be vaccinated against a swarm of diseases, including whooping cough, influenza, measles, yellow fever – and, since 2012, pneumococcal disease and rotavirus, respectively, the main causes of two of the world’s leading child killers, pneumonia and diarrhoea. GAVI helps fund the introduction of some of these vaccines, and supports Ghana’s state health service and local partners with training and improvement of refrigerated vaccine storage.

Double roll-out

The double roll-out of the pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines in 2012 was seen as a test for the West African country. It was the first-time any African country introduced two vaccines simultaneously, but the introductions passed off with very few hitches.

“It was important to continue to educate mothers and the public that there’s these new vaccines, and what they prevent,” says Cynthia Charpo, 30, a community health worker in Dodowa, a town north of Ghana’s capital, Accra. “Because it was a new thing, people wanted to know what reactions there might be. But most people just accepted it, and we are immunising even up to today, and nobody is complaining.”

Model

The success with the pneumococcal and rotavirus campaigns means that Ghana is increasingly a model for its neighbours.

Ghana’s ability to introduce two vaccines at the same time, and its general success with immunisations, is down to targeted training, national and local government support, good communication, and databases for vaccine coverage, says K.O. Antwi-Agyei, who heads the country’s national disease control unit.

“We put a lot into education and training,” he says. “We build a culture of data management and using data for decision making, and we have a decentralised system of government. In addition, we work closely with our civil society groups so that for us when we talk about a health system, it’s not the government structures alone. We use all available opportunities.”

Working

It is working: coverage of vaccines against meningitis, polio and diphtheria, tetanus and whooping cough are all above 90%, according to World Health Organization figures for 2012.

Measles, which used to kill more Ghanaian children than any illness apart from malaria, has been all but eradicated.

Loud-hailer

A short drive north of Dodowa, Esther Oku-Afari, a 49-year-old nurse, is setting up another outreach clinic in a bus station, calling mothers to the front with a loud-hailer.

In the 25 years that she has worked in this district, around the town of Larteh in the hills north of Ghana’s capital, Mrs Oku-Afari has seen the impact of vaccines on countless children.

“It’s been very good because hitherto, measles was common, whooping cough was common, but since vaccination has been going on, you can hardly now find somebody with these conditions,” she says. “I don’t remember the last time we had measles.”

Free for all children

GAVI’s funding of vaccines means that they are given for free to all children who need them – which is critically important, she adds.

“It’s a very big incentive because if they were supposed to pay, I doubt that there would be many people who could afford it,” Esther Oku-Afari says. Women visiting the clinic with their children gathered to listen behind her and nodded their agreement.

Challenges

There are still challenges, however. The area where these makeshift clinics were held is prone to heavy rains, and roads beyond the main towns are in poor condition here and in many places across the country.

Electricity for refrigeration of vaccines beyond the larger clinics can be scarce. And there are still small pockets of resistance, where families refuse to have their children immunised because of religious teachings or because of international anti-vaccination campaigners, whose propaganda people read on the Internet.

Success stories

But these are difficulties that Ghana is best placed to overcome, says Ebenezer Appiah-Denkyire, Director-General of the Ghana Health Service.

“We’re proud to say that because of our success stories, we are now able to introduce new vaccines that run without difficulty, and that’s a lot to do with the support we’ve received, including the role GAVI has played,” he says.

Dr K.O. Antwi-Agyei

| NAME: | K.O. Antwi-Agyei |

| PROFESSION: | disease control unit programme manager for the Ghana Health Service |

| EXPERIENCE: | programme manager for immunisations in Ghana since 2002 |

| BIGGEST CHALLENGE: | ensuring the cold chain is working efficiently; guarding against complacency as immunisation risks becoming a victim of its own success. With disease levels dropping due to vaccination, some families are questioning whether their children need to be immunised |

| LOCATION: | Ghana Health Service, Accra |

| POPULATION: | 25,904,598 (Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: World Population Prospects, the 2008 Revision. New York, 2009) |

GHANA

Strengths

Strong commitment by government, consistently high performer on all aspects of GAVI-supported activities, proven capacity to introduce two vaccines simultaneously, excellent quality of data, well-trained staff.

Challenges

Some inconsistencies in coverage. For example, fewer children are receiving pneumcoccal vaccine than the pentavalent vaccine.

Overview

Ghana has one of the best-performing immunisation programmes in the developing world and is increasingly a model for its neighbours. The recent double roll-out of the pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines was seen as a test for the West African country, but the introductions passed off with very few hitches. K.O. Antwi-Agyei, who heads the country’s national disease control unit, attributes Ghana’s success to targeted training, government support, good communication and strong data keeping.

Strengths

Strong commitment by government, consistently high performer on all aspects of GAVI-supported activities, proven capacity to introduce two vaccines simultaneously, excellent quality of data, well-trained staff.

Challenges

Some inconsistencies in coverage. For example, fewer children are receiving pneumcoccal vaccine than the pentavalent vaccine.

Overview

Ghana has one of the best-performing immunisation programmes in the developing world and is increasingly a model for its neighbours. The recent double roll-out of the pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines was seen as a test for the West African country, but the introductions passed off with very few hitches. K.O. Antwi-Agyei, who heads the country’s national disease control unit, attributes Ghana’s success to targeted training, government support, good communication and strong data keeping.

Q Can you tell us how you became involved in this work?

Dr Antwi-Agyei: when I was working as a young medical officer, I saw that a lot of children were dying of measles. We were doing our best to save them, and yet, unfortunately, we lost them.

When I went for further education, I realised that if we can prevent the disease from occurring in the first place, aren’t we saving more lives? So I developed an interest in preventative medicine. Since 2002, I’ve been the programme manager for immunisations in Ghana.

Q How has the situation changed since you started out on your career?

Dr Antwi-Agyei: in the 1980s measles was the number two killer of children in Ghana, second to malaria. Then we began introducing vaccines, and for well over 10 years now no person has died from measles in Ghana, which of course has contributed to our reduction in overall childhood mortality.

We believe if we fight vaccine-preventable disease, we’ll reduce that further. That’s why we introduced the pneumococcal and the rotavirus vaccine, to address the next two major causes of under-fives’ illness and deaths in Ghana: pneumonia and infant diarrhoea.

You know, malaria is still the top cause. But even for that we are expecting that one day there’ll be a vaccine against malaria.

Q How has GAVI helped?

Dr Antwi-Agyei: before, we could only afford traditional vaccines. The more expensive vaccines were beyond our reach. With GAVI, we’re now able to afford the pentavalent vaccine (against diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis, hepatitis B and Haemophilus influenzae type b) because of the principle of co-payment. Now, we’ve also been able to introduce pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines.

GAVI’s objective is to make vaccines, which are underused or underutilised because of their cost, available to poor countries, and they’ve played a major part in Ghana. They’ve also supported us with a lot of training and also to improve our cold chain capacity.

Q Why do you think Ghana has such a successful vaccination programme?

Dr Antwi-Agyei: we have a good workforce, who have been exposed to training with each successive introduction of new vaccines, training that cascades from the national to the regional to the district level and down.

We have built a culture of data management, and using data for decision making, which means that it’s up to each district to improve upon its performance. If you attain 80%, 85%, 90%, it’s not an end. For immunisations, a new cohort is born every year; babies are being born every day.

We also have strong logistics teams and good stock management. I’d say that for well over ten years, we’ve not run short of vaccines, at least at the national level. What also helps in our success is that we have a decentralised system of government, which means each level – national, regional, district – knows what its functions are, and prioritises them. And I’ll say that the leadership at the national level has also been quite stable. For example, I’ve been in this post for ten years.

We also work closely with our civil society groups, so that when we talk about a district health system, it is not the government structures alone. We use all available opportunities.

Q Do your vaccine teams encounter any resistance? Are people suspicious of the immunisations?

Dr Antwi-Agyei: generally in Ghana, I think immunisation has acquired a big name and it is well-respected. People generally trust that health workers will bring what is good. People tell us that they were aware of what measles was doing and how, through vaccinations, measles as a disease has gone down and their children are no longer dying.

But I will say that there are a few individuals here and there who would read things on the Internet, or hear what someone says when they buy air time to talk about immunisation as evil. During vaccination campaigns, occasionally we will encounter somebody who says no, sometimes on religious grounds. And then you need to try to convince them.

Q What do you see as some of the challenges facing vaccination campaigns in Ghana in the future? Where do you see the most room for improvement?

Dr Antwi-Agyei: we need constantly to be working on the cold chain, because once you get the vaccines, storing them is critical.

Communication is important, because immunisation can become a victim of its own success - once the disease goes down and people are not seeing it and the harm it can do, complacency sets in. People think, “There’s no disease, why are you vaccinating us?” We need to constantly drum home to people that once disease incidence is low, we still cannot stop our vaccination.

Alongside this, as more and more vaccines are coming up, people are also becoming a little uncomfortable that their children are being given too many vaccines. So we also need to refute this idea.