World Cancer Day: the little-known role of vaccines in fighting cancer

Each year almost 9 million people die of cancer worldwide. By 2030, this figure is expected to increase to 13 million. Like infectious diseases, this growing scourge hits developing countries the hardest: close to 70% of all cancer deaths are in low- and middle-income countries.

Many types of cancer can be prevented through healthy habits, including physical exercise and the avoidance of alcohol, tobacco and unprotected sex. But part of the solution also lies with prevention through vaccines.

Vaccines versus cancer

Most people are aware of the role of vaccines in preventing infectious disease, but many do not realise that they can also protect against cancer. This is because some cancers are caused by viruses. By preventing these viral infections, vaccines can halt the rise in some types of cancer.

There are two cancer vaccines, both of which Gavi is supporting:

Hepatitis B vaccine protects against infection with hepatitis B virus, which can cause liver cancer – the second most lethal type of cancer among men after lung cancer. When Gavi was set up in 2000, less than 5% of all low-income countries had introduced hepatitis B vaccine nationally. Now, largely thanks to our public-private partnership model, the 73 poorest countries in the world are providing the vaccine through their routine immunisation programmes.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine protects against the HPV virus and can prevent up to 90% of all cervical cancer cases. Gavi started supporting the vaccine in 2012, recognising that the vast majority of all cervical cancer deaths are among women in developing countries.

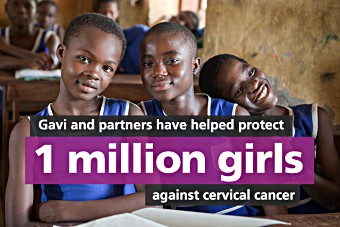

Gavi’s support for HPV vaccine has been a game changer. Since the first demonstration programme in 2013, countries have vaccinated more than 1 million girls with the Alliance’s support. By 2020 it is expected that up to 40 million girls will have been protected against cervical cancer, preventing 900,000 deaths.

According to WHO, vaccination against hepatitis B and HPV could prevent 1.1 million cancer cases every year.

Lower prices

The Gavi model has also helped make both vaccines more affordable. Through Gavi, the poorest countries have access to HPV vaccines for as little as US$ 4.50 per dose. The same vaccines can cost more than US$ 100 in high-income countries.

The average price per dose of the pentavalent vaccine, which protects against hepatitis B alongside diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (whooping cough) and Haemophilus influenzae type b, has dropped by 48% since 2010.

Beyond immunisation: economic impact

Focusing on prevention rather than cure does not only save lives and prevent suffering, it also saves costs. According to WHO, the total annual cost of cancer in terms of healthcare costs and lost productivity in 2010 was approximately US$ 1.16 trillion. Studies have shown that both hepatitis B and HPV vaccines are very cost-effective in the vast majority of Gavi-supported countries.

New cancer vaccines in the pipeline

Several cancers are caused by virus and bacteria, meaning that they could potentially be prevented by vaccines. Tumours associated with viral or bacterial infections make up close to 20% of all cancer cases worldwide.

One of the most prevalent causes of stomach cancer is infection with Helicobacter pylori. The bacteria, found in the lining of the stomach, causes a harmless inflammation in about 85% of those infected. But in the remaining 15% it can cause stomach cancer, ulcers and gastric lymphoma. A new vaccine against stomach cancer is undergoing clinical trials.

The Epstein-Barr virus is a major cause of Hodgkin’s lymphoma and nasopharyngeal cancer (cancer in the back of the nose). The virus can also cause fast-growing lymphomas such as Burkitt’s lymphoma. These cancers are most common in developing countries, where treatment is often not available. Although several clinical trials have been conducted, a vaccine is not yet available.

Human T-lymphotropic virus has been linked with a type of leukemia and lymphoma. Some 10–20 million people around the world are infected, many of whom will develop serious complications. There is no licensed vaccine, but experimental vaccination in animal models has proved successful.