Question&Answer

Dr Olusegun Mimiko, Ondo State Governor, and

Dr Dayo Adeyanju, Ondo State commissioner for health

They have yet to be the subject of an animated series or a blockbuster movie but in Nigeria’s public health landscape, Dr Olusegun Mimiko, Ondo State Governor, and Dr Dayo Adeyanju, Ondo State commissioner for health, are the ultimate dynamic duo.

Dr Adeyanju’ s super powers are in evidence today as he shows off the Ondo State Cold Storage Facility, a brand new building that sits alongside a construction site where a health centre is taking shape - and barely 20 feet from the crumbling stone barn that formerly served as the vaccination store.

For Adeyanju, the site represents a good metaphor for health care in his state. “Our people are enjoying the best health care in the country,” he says. “But we are working on projects to make it even better.”

Raising the level

Nigeria’s system of government is federal, and each state has considerable autonomy, including in how it organises and delivers health care. This system translates into marked differences in the quality of health care and health between states. Nigeria’s other states have now started to judge Ondo as the bar against which to measure their own health care services, and Dr Adeyanju wants to keep raising the level.

“We have a very supportive governor, Dr Mimiko, and the entire state government is very committed to health services,” he says.

Good guy doing a good job

Governor Mimiko and Dr Adeyanju first met more than three decades ago when Adeyanju was an impressionable 12-year-old. Dr Mimiko had come to his school to give a talk about the health profession. “We spoke for a while and I said to myself afterwards, ‘He seems like a good guy doing a good job at a young age…maybe I’d like to be like him.’”

As Dr Mimiko moved up the public service ladder to become Ondo State commissioner for health, Dr Adeyanju graduated medical school and began working at the state hospital. This first job left him feeling discouraged. “I saw that I couldn’t help most people,” he says. “I thought it would be better for me to be in an area where I can prevent all these things in the first place.”

Grass-roots programmes

Dr Mimiko saw that the young doctor was frustrated and could better fulfil his ambitions in public health, so he invited Adeyanju to come and work for him at the ministry. Together they embarked on a grass roots programme that succeeded in dramatically reducing HIV and malaria prevalence in Ondo State. Then, in 2009, Mimiko was elected to the governor’s seat. With his new position came great opportunity.

“When we came on board, we had a grossly underfunded health sector with poor infrastructure, poor leadership and ill-motivated workers,” Dr Adeyanju says. “We had a state that still had polio in one of the local government areas and where infant mortality was pretty high and under-five mortality was also too high.”

Revolutionising the system

The new governor made health a priority for his administration and embarked on revolutionising the system through the Abiye project -- the Yoruba word for motherhood.

Pregnant women are the major target of the Abiye programme. Each woman gets a smart card containing biographical data, which allows health workers to track the medical history of her family. The card makes it easier to schedule postnatal care, including vaccinations for babies.

Increasing access to vaccination was the first step. But then there was the question of how to store and transport vaccines.

“The old state cold store had not been used for two months when we saw it,” Adeyanju recalls. “The ramshackle building appeared to have sat derelict for decades, with crumbling walls, a dank odour and an electrical fuse box that looked like a 10-year-old’s science project.” The generator supplying power to the all-important fridges had been bought in 1978.

Cornerstone

“I told the Governor this was not good enough, and within weeks he had set aside funds for a new store and construction was underway,” he says.

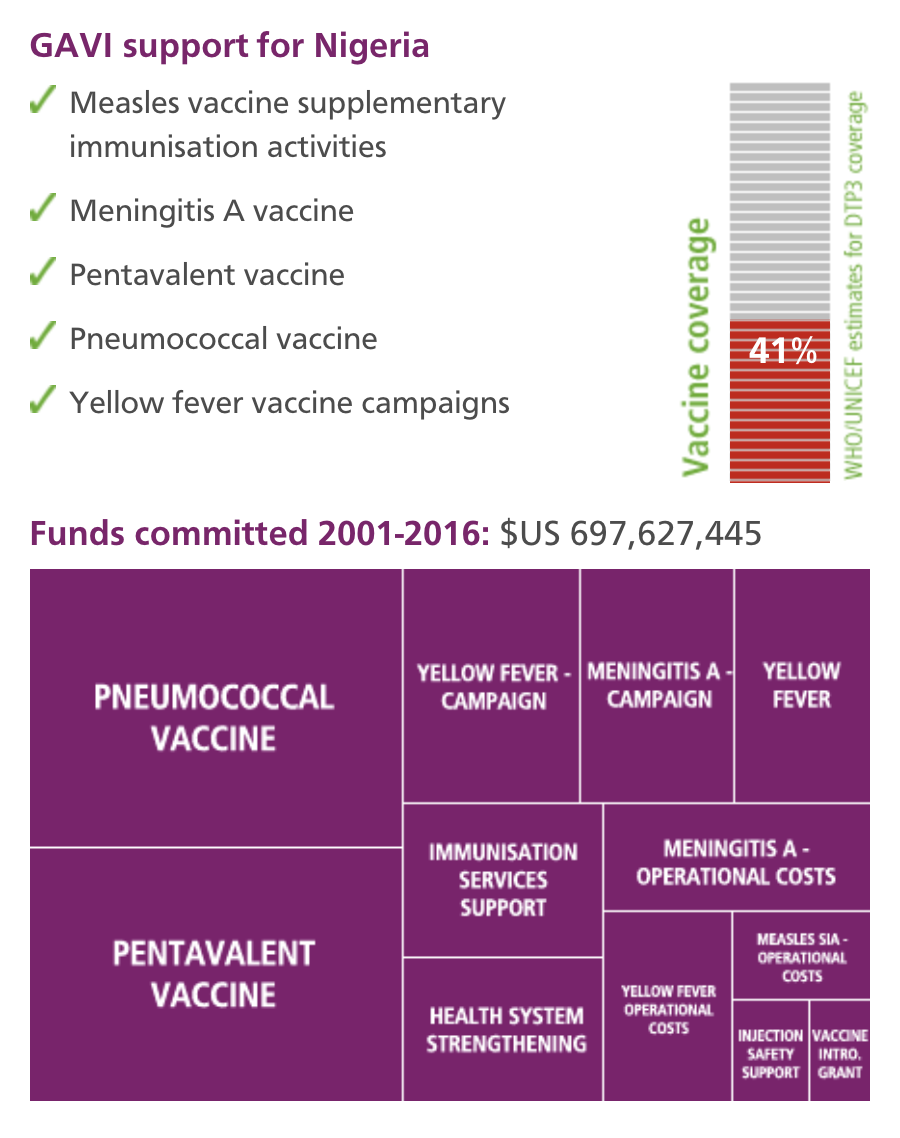

Vaccination coverage in the state is now among the highest in the country, and within the next few months Ondo will begin the roll out of pentavalent vaccine - a single vaccine that protects children against five potentially lethal diseases: tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis (whooping cough), hepatitis B and Haemophilus influenzae type b (which causes meningitis and pneumonia). Pentavalent is currently used in some 170 countries, and is increasingly being given to children in developing countries with support from the GAVI Alliance.

“The cornerstone of our health programme is the Routine Immunisation Programme, which is boosted by national immunisation days – none of which would be possible without GAVI’s support,” Dr Adeyanju says.

As Nigeria seeks to address fragmentation in its health care the GAVI Alliance, in parallel, is working on tailored approaches to supporting the country’s immunisation systems, which need to be tackled state by state. “With these generous donations we can provide a model that could transform the whole country,” Dr Adeyanju says.

And perhaps recruit a few additional super heroes along the way.