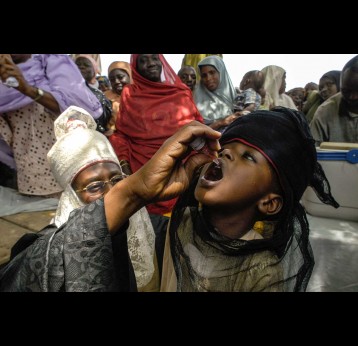

Latest articles about polio Routine vaccines: Polio

Gavi's impact

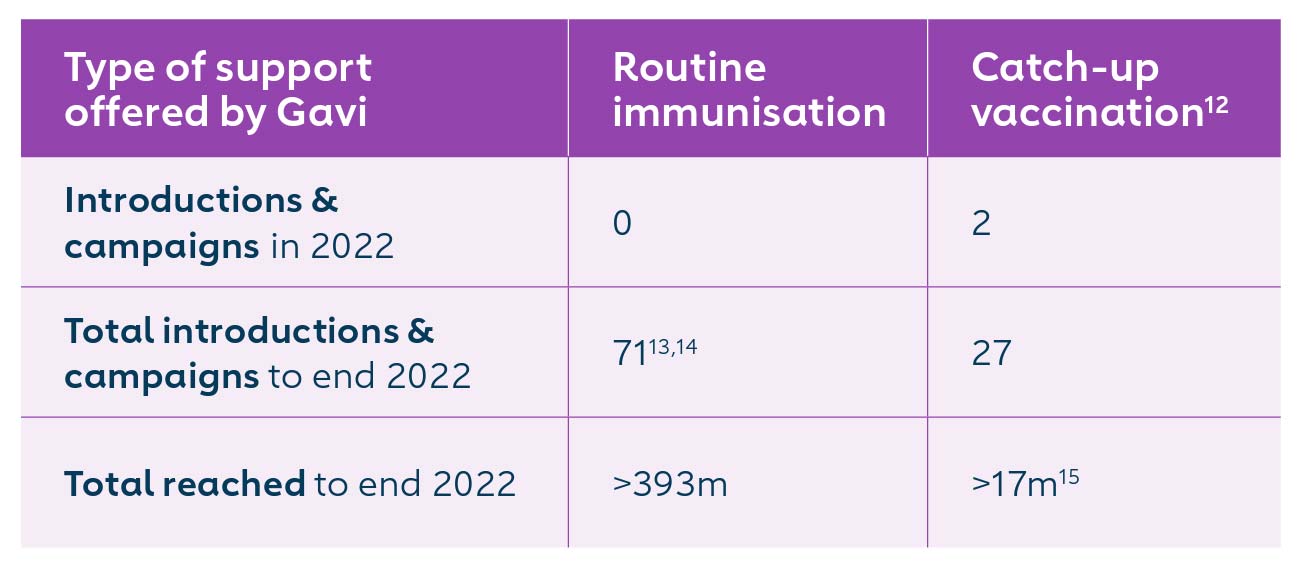

By 2019, all Gavi-supported countries had introduced the first dose of inactivated polio vaccine (IPV1) into their routine immunisation schedules – reaching a coverage rate of 81% in 2022. All but six countries have implemented catch-up vaccination activities for birth cohorts missed during the period of global supply constraints (2016–2019). The switch from a one-dose schedule to a two-dose schedule (IPV2) is progressing since Gavi's support window for IPV2 opened in 2021: by end 2022, 34 out of 63 eligible countries had switched to a two-dose schedule. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, capacity gaps and multiple competing priorities have resulted in delayed introduction for countries already approved to switch to IPV2 – and fewer new applications for IPV2 and IPV catch-up support. Twenty-three countries have not yet applied for IPV2.

The issue

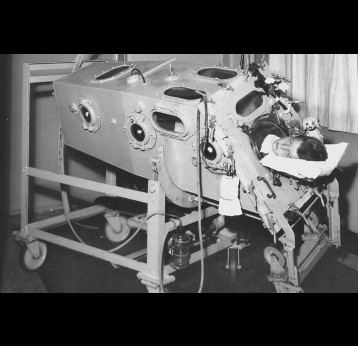

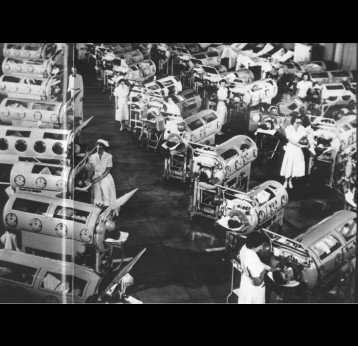

Polio, or poliomyelitis, is a disabling and life-threatening disease caused by the poliovirus. Poliovirus is very contagious and spreads through person-to-person contact. The virus can infect a person's spinal cord, causing paralysis. Paralysis is the most severe symptom associated with poliovirus because it can lead to permanent disability and death.

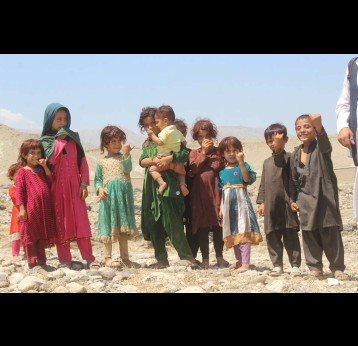

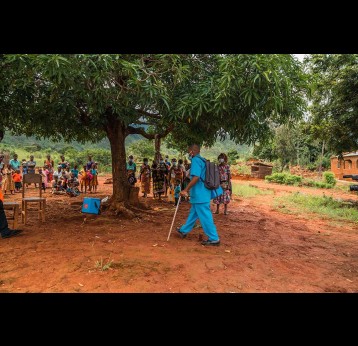

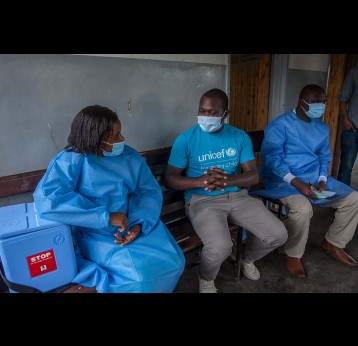

Gavi supports the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) Polio Eradication Strategy 2022–2026 through the introduction of IPV into routine immunisation programmes. When GPEI was launched in 1988, polio was endemic in 125 countries and paralysed about 1,000 children per day. Thanks to global efforts and vaccination, polio cases have fallen by 99% since then. More than 18 million people can walk today who would otherwise have been paralysed, and 1.5 million childhood deaths have been averted because of polio vaccines. Four regions of the world are certified polio-free: the Americas, Europe, South-East Asia and the Western Pacific. Only parts of two countries – Afghanistan and Pakistan – remain polio-endemic. In 2019, Gavi joined GPEI as a full member.

Gavi's response

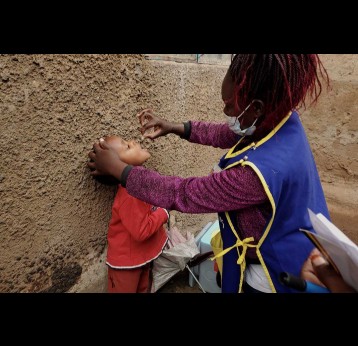

There are two types of vaccines that can prevent polio:

- inactivated polio vaccine (IPV)

- oral polio vaccine (OPV)

Polio vaccine protects children by preparing their bodies to fight the poliovirus. Almost all children (~99 percent) who get all the recommended doses of IPV will be protected from polio.

The Vaccine Alliance worked with GPEI partners to support one of the fastest roll-outs in the history of immunisation: the introduction of at least one dose of inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) into the routine immunisation schedules of all Gavi-supported countries.

The Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) recommends that countries catch up children who were missed due to global supply constraints of IPV (2016–2019), as they are currently not protected against poliovirus type 2. All but six countries have implemented catch-up vaccination activities for birth cohorts missed during this period. The Gavi Board has decided to continue support for IPV until global OPV cessation.

Starting 1 December 2023, countries eligible for Gavi support can apply to switch to a whole-cell pertussis (wP) hexavalent vaccine (hexavalent) – a six-in-one vaccine that combines the pentavalent vaccine (diphtheria, tetanus, whole-cell pertussis [DTwP], hepatitis B, and Haemophilus influenzae type b) with IPV. Countries can choose to switch to hexavalent or continue using pentavalent and IPV. Gavi Alliance partners can assist countries to assess the financial, logistical, and programmatic implications of a switch to hexavalent to determine which option is most suitable for their context.

Countries that have not yet introduced IPV2 are encouraged to introduce hexavalent or IPV2 as a matter of urgency. Click here for hexavalent vaccine programme information.